Analysis: Select a key painting and comment on the religious, political and allegorical symbolism of food and objects in terms of wealth, status and power, or the lack of.

Cookmaid with still life of Vegetables and Fruit by British painter Sir Nathaniel Bacon

- Title: Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit

- Creator: Sir Nathaniel Bacon

- Date: c.1620-5

- Provenance: Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1995

- Physical Dimensions: 1510 x 2475 mm

- Original Title: Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit

- Type: Painting

- Rights: Tate

- Medium: Oil paint on canvas

Sir Nathaniel Bacon did not paint professionally, although he was a skilled amateur artist. Very few works attributed to him survive, so the appearance of this work on the art market presented the Collection with a rare opportunity for acquisition. Furthermore, the subject matter, a cookmaid surrounded with lavish produce, more usually associated with Dutch and Flemish art, is highly unusual in England for the period and associated only with Bacon. Every item depicted is known to have been growing in England: Bacon himself grew melons on his Suffolk estate

Additional Viewing Notes: ‘Cookmaid’ and market scenes, popular in the seventeenth century, evolved in the Low Countries from a genre practised by Pieter Aertsen (c.1533-c.1573) and his pupil Joachim Beuckalaer, which combined contemporary kitchen scenes with a New Testament episode beyond. Bacon could have seen such works on a visit he made to the Low Countries in 1613. An inventory of 1659 connected to the will of the artist’s wife lists ‘Ten Great peeces in Wainscote of fish and fowle &c done by S:r Nath: Bacon’ (quoted in Gervase Jackson-Stops, ed., The Treasure Houses of Britain, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 1985, p.140). Two other ‘Cookmaid’ pictures are known to exist: Cookmaid with Still Life of Game and Cookmaid with Still Life of Birds, both in the possession of the artist’s descendants. The Tate’s work is possibly part of this group. Such groups were often intended to depict the four seasons or the twelve months of the year. In the case of this piece, however, although every item represented in the painting was grown in England at the time, not all would have been in season simultaneously. Bacon, according to a letter dated 19 June [1626], was growing melons at his estate in East Anglia, and he was known to have a keen interest in horticulture. The subject would most likely have had erotic connotations. The abundance of ripe melons surrounding the cookmaid echo her voluptuous cleavage.

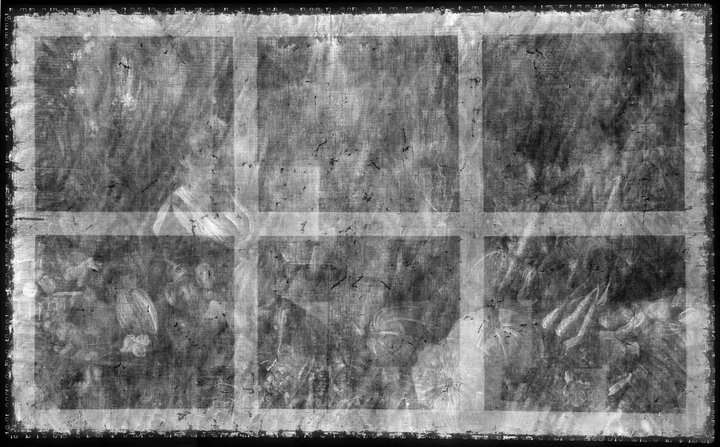

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1510 x 2475 mm (fig.1). The support is a single piece of very fine, plain-woven linen. It has 15 vertical threads and 17 horizontal threads per square centimetre. Cusping of the weave around the edges indicates that it was primed as a single piece on a strainer or stretcher that has not survived (fig.2).1 When acquired by Tate in 1995 the lined painting was attached to an adjustable pine stretcher. The style of this stretcher and of the lining (linen canvas with red lead in oil as the adhesive) suggested an origin in the late eighteenth century, although the use of red lead as the lining adhesive would be unusual at any time. The stretcher was slightly smaller than the original would have been; the ground and the painted design strayed over onto its tacking edges on the top, bottom and left sides.

No underdrawing is visible with the unaided eye or infrared. Cross-sections and surface examination indicate an additive or sequential style of painting. The cabbage leaves, for example, were first laid in with opaque bluish tones composed of smalt, azurite and red lake. The deep shadows were added on top with a mixture containing azurite, red lake, vermilion and black; the highlights with pale green mixed from azurite, lead tin yellow and smalt. Finally thin glazes of red lake or red lake mixed with azurite were applied here and there (fig.4). The purplish blue grapes at the bottom edge were laid in with opaque grey paint, then glazed all over with semi-translucent purplish red before the opaque blue paint was applied selectively on top (fig.5).

The range of pigments is fairly restricted. Azurite mixed with lead white was used for the cookmaid’s blue bodice, with smalt and black added for the shadows. The sky is a mixture of white lead and smalt. The bright yellow of the melons and other fruit is lead-tin yellow. The sixteenth-century miniaturist and writer Edward Norgate tells us in his bookMiniatura of 1627−8 that Bacon made his own yellow lake (‘pinke’) from the plant Dyers’ Broom and analysis of this painting showed that Bacon used this pigment mixed with ochres and azurite to make the greens of the distant foliage, and also on its own as a top glaze.4 The dye was fixed to a substrate containing calcium, aluminium and sulphur, as related in the recipe. The red plant dye in the red lake is cochineal, almost certainly from the New World. It is possible that the painting has undergone some fading. Cross-sections from the sky and from the blue grapes suggest that there has been some degradation of the smalt, and examination of the red skirt suggests it was originally glazed with red lak