Rafał Milach (born 1978) is a Polish visual artist and photographer. His work is about the transformation taking place in the former Eastern Bloc, for which he undertakes long-term project. He is a nominee member of Magnum Photos. Rafal Milach is a visual artist, photographer, and author of photo books. His work focuses on topics related to the transformation in the former Eastern Block. His works have been widely exhibited in Poland and worldwide, and can be found in the collections of the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, the ING Polish Art Foundation, Kiyosato, the Museum of Photographic Arts (Japan), and Brandts in Odense (Denmark).

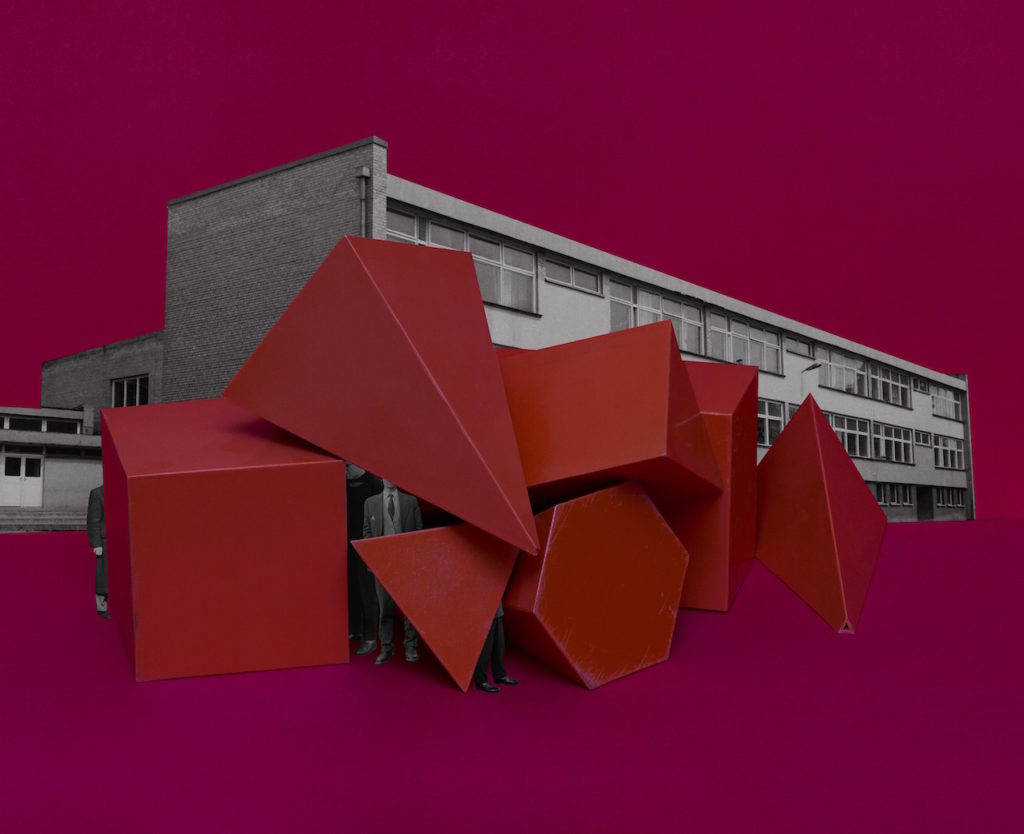

I will be personally looking directly at Milach’s work ‘The First March of Gentlemen’ which was developed in 2017. The book is contextually produced surrounding the historical events around the town of Września and this came to be the starting point for reflection on the protest and disciplinary mechanisms. In the series of collages, the reality of the 1950s Poland ruled by the communists blends with the memory of the Września children strike from the beginning of the 20th century, which was a protest of Polish children and parents against the Germanization. This shift in time is not just a coincidence, as the problems which the project touches upon are universal, and may be seen as a metaphor for the contemporary social tensions.

“The initial idea of working with the archive was sustained, but the topic changed as I began looking for material that could occupy two spheres – discipline and pacification, and the sphere of freedom – and to bring these elements together in a series of collages.”

The above quote has been taken from an interview that Rafal Milach took part in with the British Journal of Photography, over the subject of ‘The First March of Gentlemen’, I found this quote useful to me while researching having used my own island’s archives as something to be used in my photographs and in montages. It intrigued me the way that he speaks about the subjects changing to go into a ‘sphere of freedom’ as the initial subject on looking is relating to a time of no freedom and occupation and I have just found it intriguing to see the way in which the photographer views and uses the archives as context before going in and looking at the book and photographs as a whole.

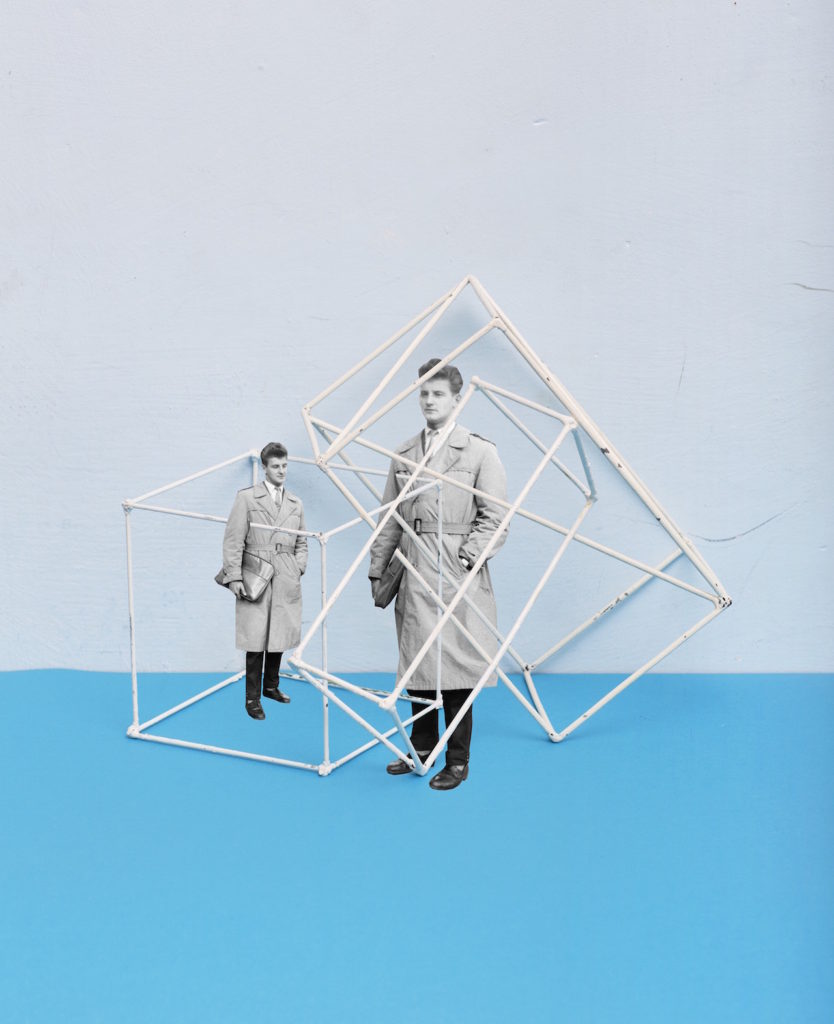

Below shows my chosen photograph of Rafal Milach’s series. When first looking at the photographs we can see the same man, produced twice with photomontage, encaged in two geometric tools. Contextually these shapes and objects were brought into and across schools to be used as teaching tools for subjects such as mathematics, in the case of the book, as you slowly move through the photo-book the figures used from the archives slowly become more entrapped and claustaphobed into these instruments. The figure in the photograph seems looking quite dapper, he stands with not much authority but not as a suppressed minority, however this stand of posture is all juxtaposed with the fact he is encaged in this structure metaphorically speaking it could be taken and seen as a sign of the freedom they had or the lack of. This photograph was not produced all in camera, it is montaged together meaning he subject is unaware of the cage around him.

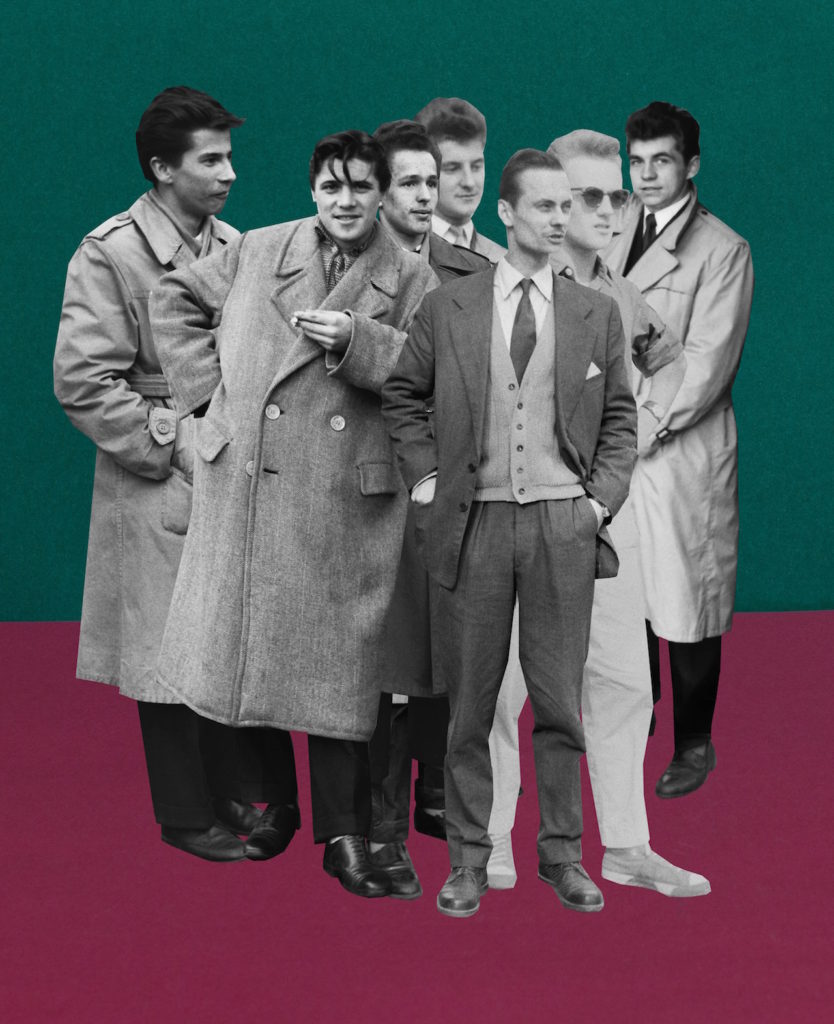

Milach found the archived photographs in the work of local amateur photographer Ryszard Szczepaniak, and his archive of images shot in Września during the 1950s and 1960s. He photographed people in formal street poses, many of them while on leave from the military, some of whom came from the Armia Ludowa, a communist partisan force set up by the Polish Workers’ Party while under German occupation during World War II. We can see from the photograph below and those alike in the mood board they pose well-dressed, whether in uniform or not, they are as Milach described them ‘dandy-esque’ figures.

Quite literally Milach has detached these figures from their photographs and their surroundings. He is placing them on brightly coloured backgrounds, a hint to child-like features, and he is displacing them on the page and contrasting them. This decision can be contextually backed by looking at what Milach speaks about when describing the figures. – “They were a poorer version of the glamour they probably knew from American films,” “This intrigued me… The photo shoots were somehow detaching the guys from the context of contempt in those days. The 1950s in Poland was a pretty oppressive time in terms of the communist regime, and these guys were just having fun in some remote areas within Września county… posing, staging shooting scenes… It was like being part of the system, but making a joke out of it.”