Rafal Milach

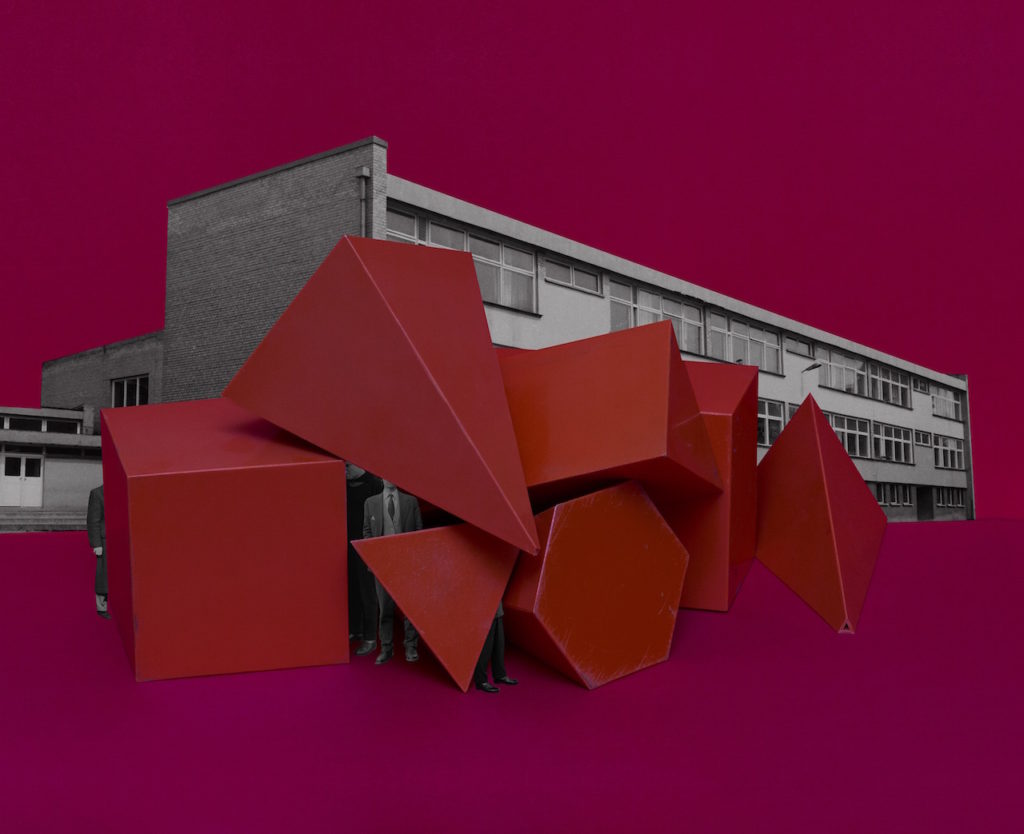

The First March of Gentlemen, a 72-page photobook composed of collages that mingle elements illustrating the 1902 Children’s Strike in the city Września. The children striked against the Germanisation of their education. Ther Germanisation would mean that physical violence would be enforced and Polish, their mother tongue would be eradicated from the classroom. It has become synomynous with Września. The First March of Gentlemen is a fictitious narrative that can be read as a metaphor, commenting on the social and political tensions of the present day. Rafal Milach explained that “The most important thing was to create a story that would be accessible to everyone because this is, in the first place, my vision of a society, in which individuals can protest in the public space, regardless of consequence,” he explains. “The initial idea of working with the archive was sustained, but the topic changed as I began looking for material that could occupy two spheres – discipline and pacification, and the sphere of freedom – and to bring these elements together in a series of collages.”

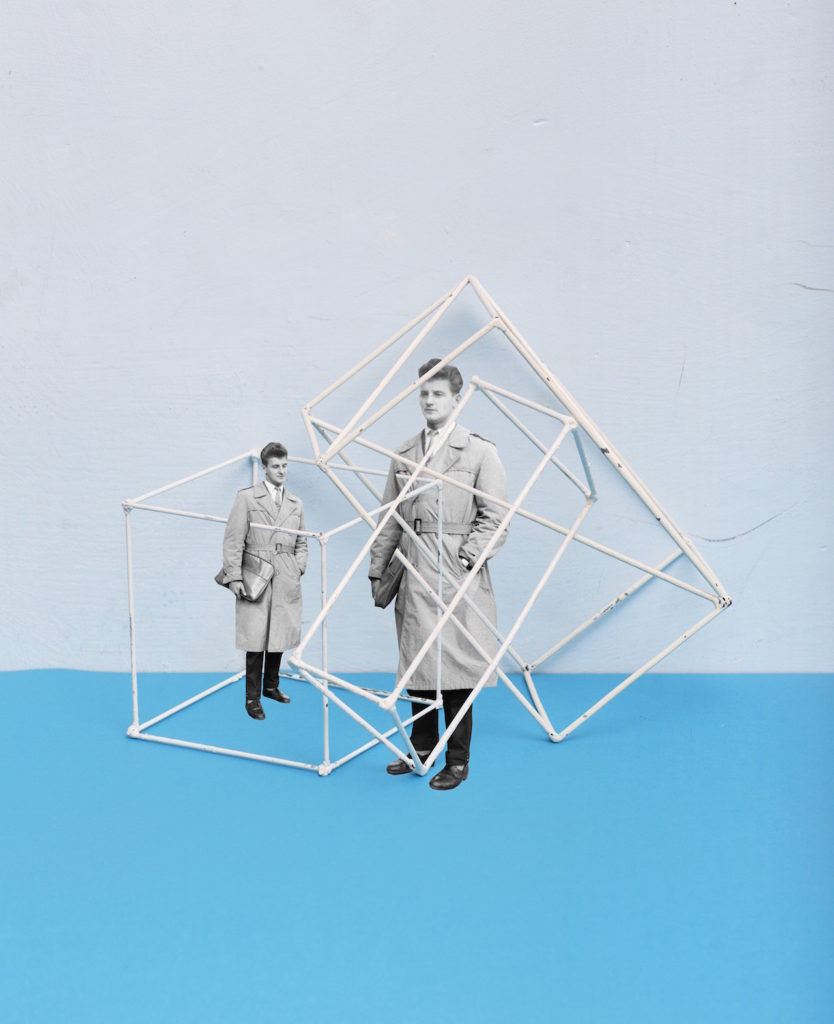

Milach found and used the work of ametuer photographer Ryszard Szczepaniak. His archive consisted of images shot in Września during the 1950's and 1960's. He photographed his and his brother’s friends in formal street poses, many of them while on leave from the military, some of whom came from the Armia Ludowa, a communist partisan force set up by the Polish Workers’ Party while under German occupation during World War II. Milach detaches them physically, cutting out the figures and pasting them onto brightly coloured backgrounds, hinting at ideas of contrast and displacement. The book was designed by his wife Ania Nałęcka-Milach, and it references a children’s exercise book in its choice of size and coloured papers, bound by a long red thread to contain its assembly. The design is “like a toy, like a candy – something nice to look at and to touch,” Milach says. “But it’s only a camouflage; a beautiful skin to disguise these spheres, to somehow smuggle them into your daily life” – just like the jubilant propaganda posters of the 1950s, or the cheery chat shows on the newly nationalised television stations of today.

Information from: https://www.bjp-online.com/2018/06/milach-gentlemen/