Still-life, by definition, is a work of art depicting an arrangement of objects (such as fruits or flowers), that is either painted, photographed or drawn. Still-life art-work makes use of inanimate objects, which are often easily recognizable and common (such as foods, books and plants). Still life became popular in western societies during the 16th century, and since then has remained a distinct genre of art work thanks to its malleability; as using inanimate objects makes it much easier for artists to experiment and manipulate the objects and scenery, to create the piece of art that best suits their requirements/themes. Still-life artwork often focuses on exploring the form, shape, colour, texture and composition of the objects, while often allowing the artist to include more subtle meanings and metaphors in their work. Below are some examples of still-life work, painting, drawing and photography:

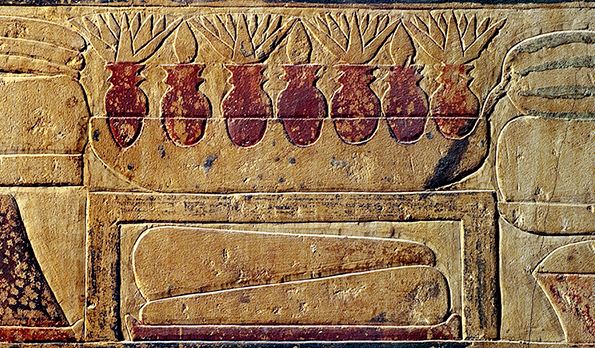

Paintings of inanimate objects have existed since ancient Egypt and Greece, with the Egyptians often placing the artwork in tombs in the hopes that the deceased would be able to use these objects in the afterlife, and Greeks depicting still-life artwork on vases. Although still-life artwork was used for many thousands of years, it was not until the Renaissance that it became its own popular genre of art.

This is an example of an early Renaissance still-life piece, created by Dutch painter, Brueghel

This is an example of the ancient Egyptians use of still life in their art. Here is a set of flower pots depicted on a wall.

During the Renaissance, still-life became a very popular way of depicting christian imagery and themes such as mortality, life and, more controversially, sexuality. Still-life was especially popular in 17th century art in Dutch and Northern Europe, with Dutch still-life specialists such as Willem Heda and Jan van Huysum producing work that followed the still-life genre.

The above image is a still-life painting produced by Jan van Huysum

This painting is a still life painted by

Willem Heda

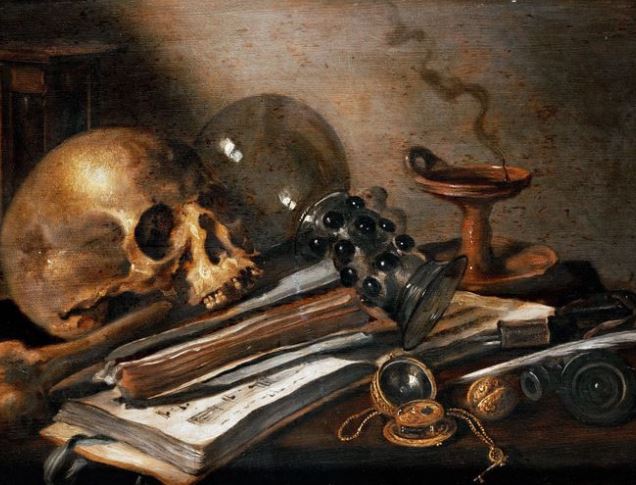

Still-life artwork often challenged societies views in the sense of personal possessions and class, for example, some artwork was made with the idea that love for material objects is meaningless, and other works depicting skulls often brought to light our own mortality. An example of this can be found in Roman works, which depicted skulls and the phrase Omnia mors aequat (Death makes all equal).

Vanitas paintings (images depicting metaphors for death/illustrating it’s inevitability) also became popular during the Renaissance. At this time, it became common to include skulls, hour-glasses and dead animals in paintings in order to reflect the delicacy of life and the inevitability of death.

Here is an example of a vanitas painting, depicting a skull.

This is an example of a piece of Renaissance art depicting dead animals, thus reflecting the same meanings as the traditional vanitas skull.