Francis Foot

Jersey Archive

The Jersey archive-located on Clarence road- is where all of Jersey’s history is stored and preserved, which contains collections recognised by UNESCO.

“The Archive is the Island’s national repository holding archival material from public institutions as well as private businesses and individuals. “

-Jersey archive website

Materials from private individuals as well as public institutions are stored in this location. The archive can be used to do things such as tracing family history, and learning further about Jersey during the occupation.

The archive contains many things such as occupation registration cards, Images from the Jersey Evening Post, hospital records, will and testaments and even textiles. The archive’s highest priority is the preservation of documents. Documents are carefully placed in acid free materials and kept in the correct conditions. Although collecting and preserving history is very important to the archive, they also want to make the archives accessible to the local and worldwide community which is why their collections are also online.

The role and purpose of the archive

The role of the archive is to help protect and preserve Jersey’s history so that residents and other people interested are able to learn more about the island’s history. This is important since remembering history is how societies learn from their past mistakes, learn and grow. The archive’s purpose is to give people a clearer understanding of why things are the way they are today, through teaching and providing knowledge of what happened in the past.

“Researchers can use archive resources to trace their family history, the story of their house or street and to find out more about the German Occupation of Jersey during the Second World War.”

-Jersey archive website

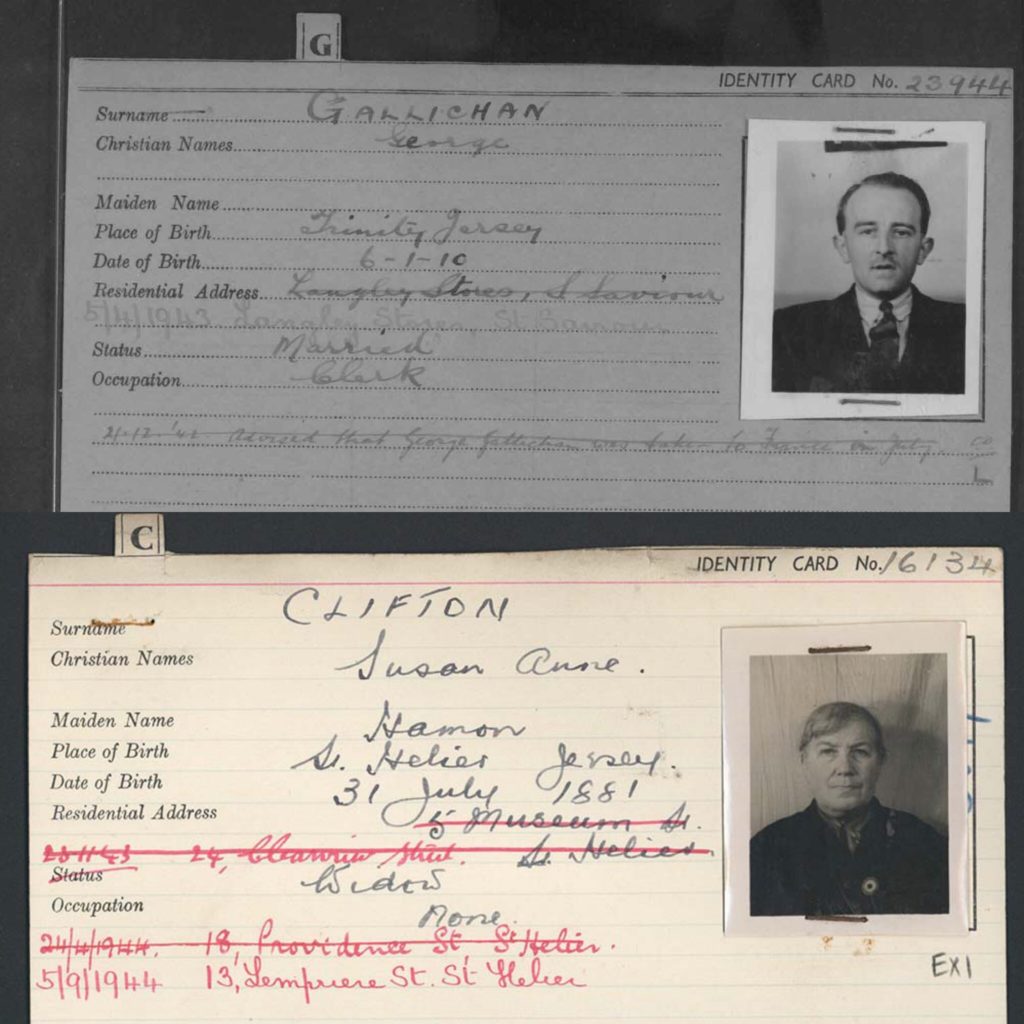

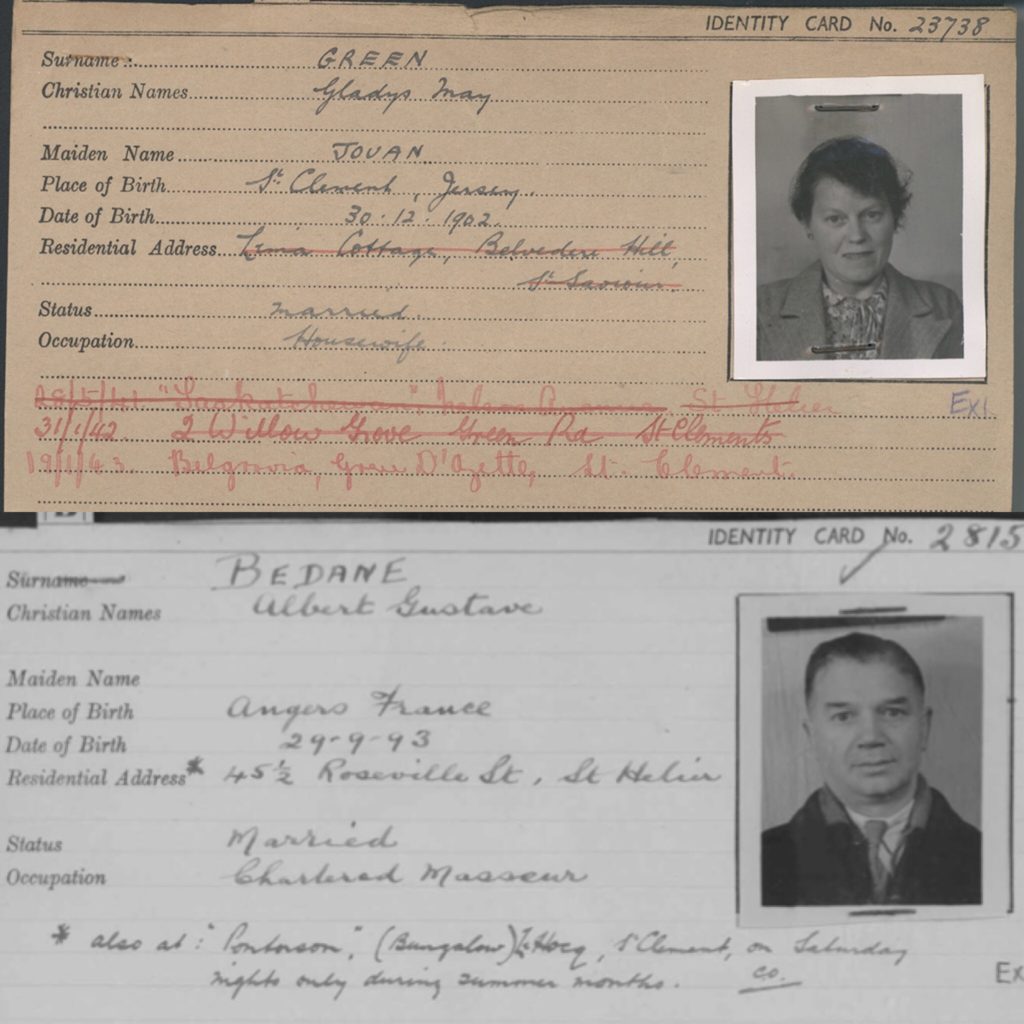

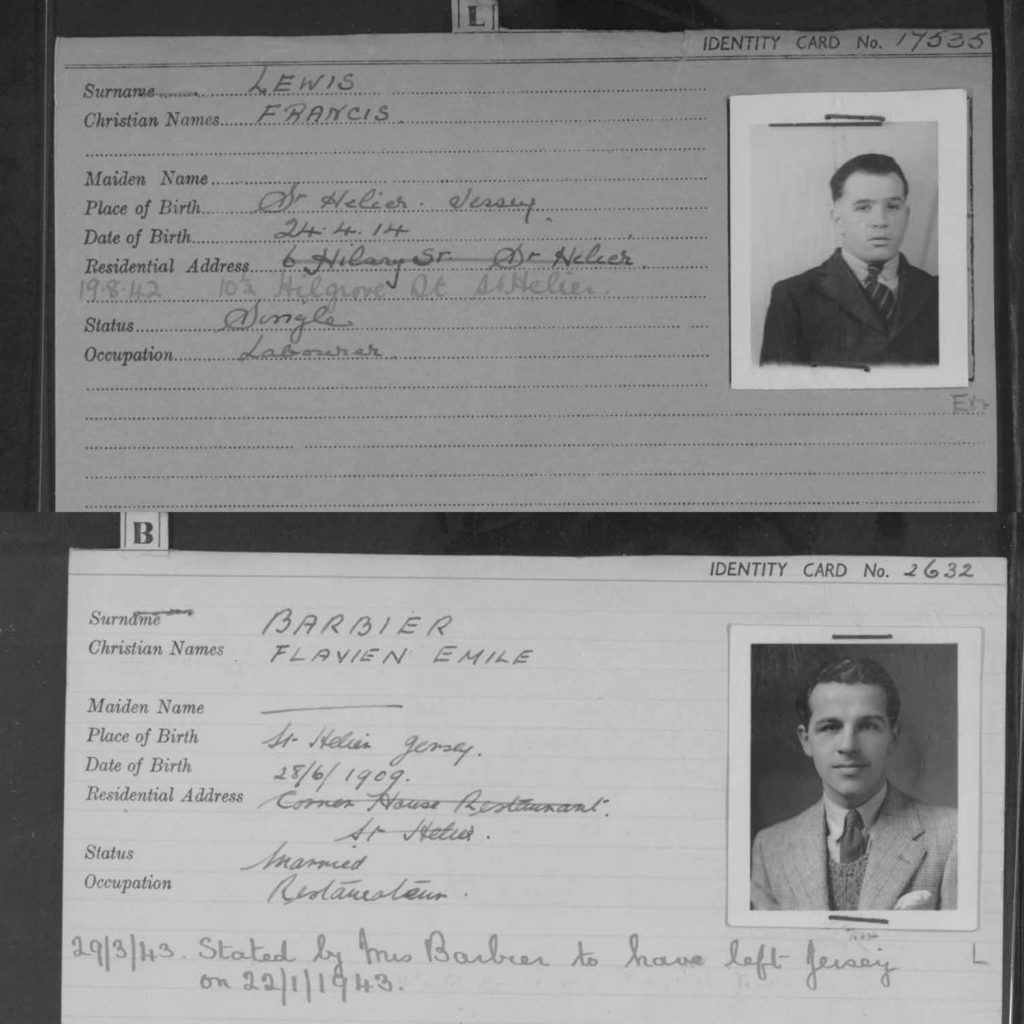

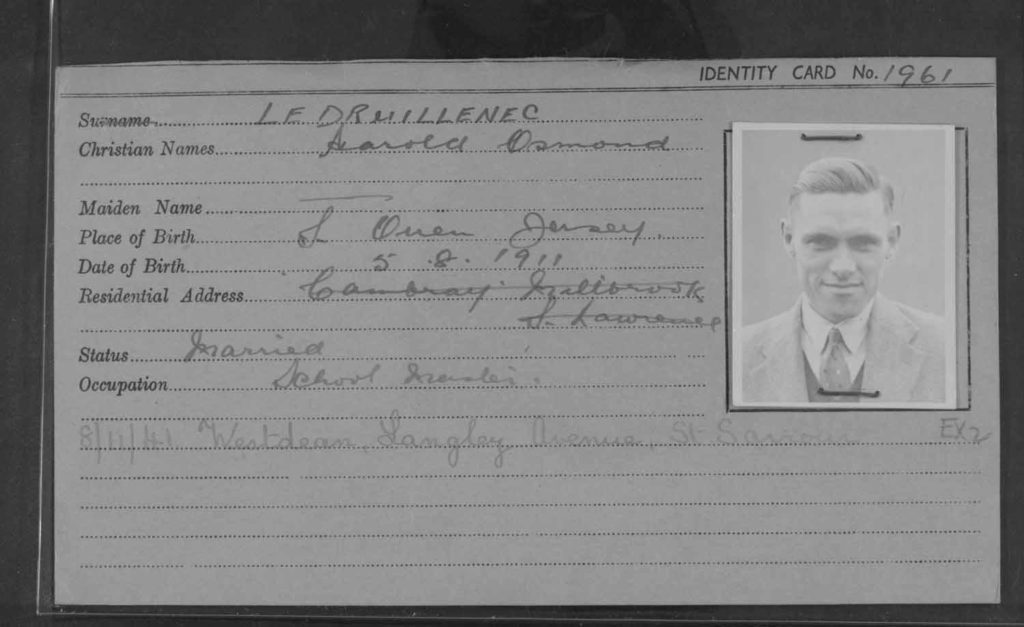

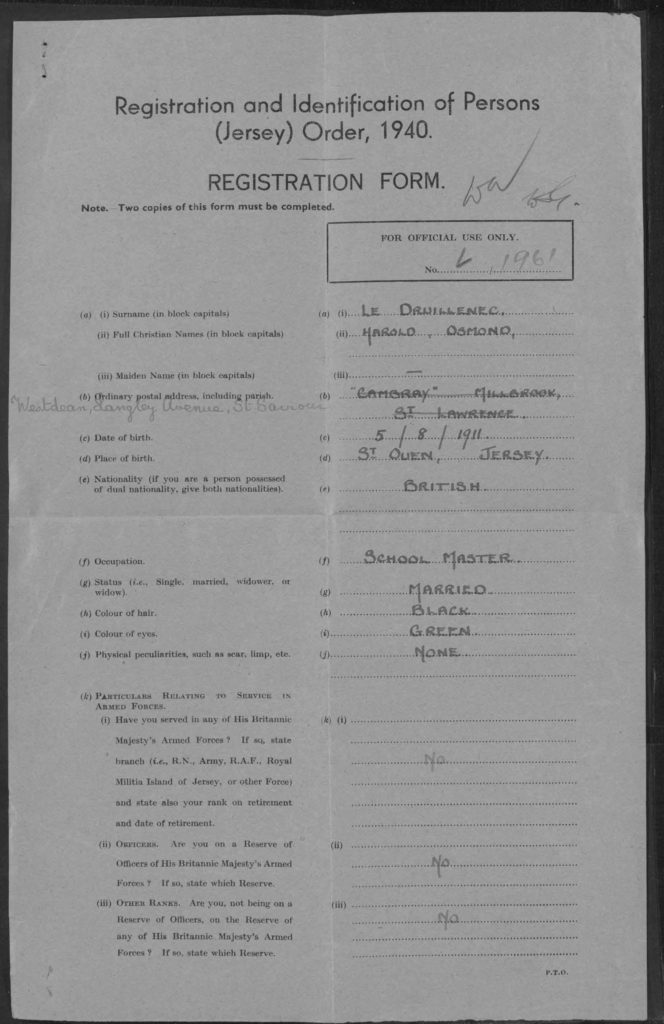

In December 1940, it was announced to the Jersey people that anyone over the age of 14 had to be officially registered under the Registration and Identification of Persons (Jersey) Order, 1940. This was put in place to control and restrict the movement of Jersey people during the occupation.

“The Archive holds over 31,000 registration cards of those individuals who lived in Jersey during the German Occupation. Each registration card contains personal details, such as name, address, date and place of birth, maiden name and occupation. The cards also include a passport sized photograph.” -Jersey archive website

These cards showed details of islanders living under the occupation, such as their picture, address and family details. Every islander was given a card and the Nazi authorities kept an official set which is now stored at the Jersey archive, after being kept in the bailiff’s chambers for many years after the occupation had ended.

“At first things weren’t too horrendous on the surface of it…it wasn’t until the Germans demanded that everybody be registered under the ‘Registration & Identification of Persons Order, 1940’ that things took a turn for the worse”– source

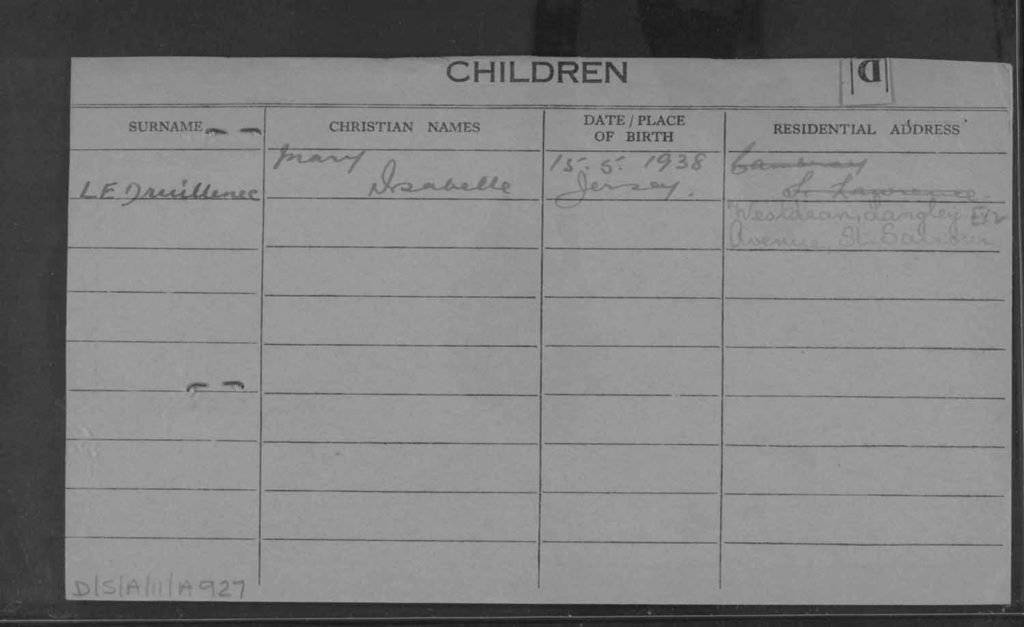

Each card was accompanied with a blue form that contained extra information that was not on the card, such as any physical peculiarities and any military service experience. Children who were under 14 had their names written on the back of their father’s cards.

The German soldiers required everyone to carry these registration cards as it meant they were easily identifiable if stopped by troops and also since the place of origin was readily available, it became easy to deport those of English origin back to England at the end of the occupation.

The cards were updated regularly and details were added if people had more children or if they moved address. As soon as children reached the age of 14, they were promptly issued with their own card.

Many of the Jersey occupation registration cards have been listed by UNESCO, which means they are registered as they have important cultural or historical significance.

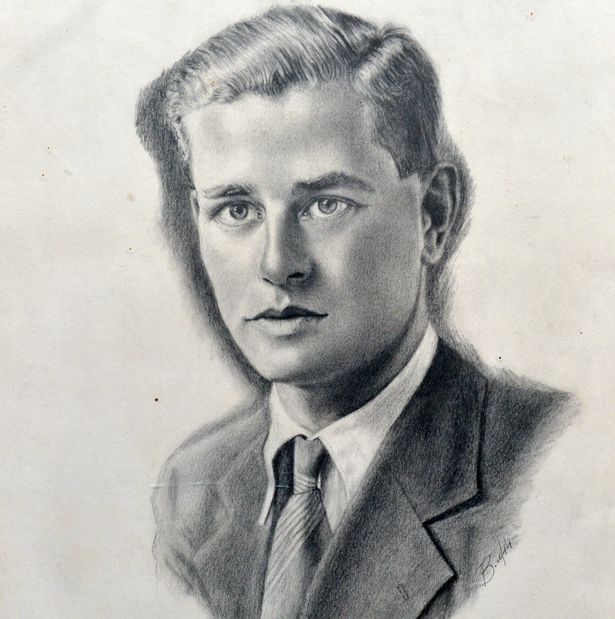

Above you can see the registration card of Jersey Resident, Harold Le Druillenec. The card tells us that he was born in St. Ouen, which is in the North West of Jersey. Mary Isabelle Le Druillenec, who was born on 15/05/1938, is registered as his child on the back of the card. Below you can see his blue registration form showing that he was British, a school head master, married, had black hair and green eyes.

After researching Harold further I learnt that him and his family had a very interesting backstory. Harold had a sister named Louisa Gould, who hid a Russian slave worker in her house during the occupation named Feodor Burriy (nicknamed Bill) in 1942. Since Harold was an educated man, and a teacher, he taught Feodor how to speak English along with his siblings. An informer later reported them to German officials and Harold, Louisa and their sister Ivy Foster were taken to German court where they were accused of assisting an escaped prisoner.

Harold was found not guilty, however was imprisoned for 5 months since the Germans discovered a radio while searching for Feodor in his home. Ivy Foster who had taken Feodor in for a short time, and also sheltered a different prisoner was also sentenced to 5 months. Louisa was sentenced to 2 years in prison. Ivy avoided being sent to France with her brother and sister after a doctor at the Jersey General Hospital forged papers stating she was too ill to leave the island. Harold was sent to Belfort while his sister Louisa was sent to Ravensbruck, which was a concentration camp for women close to Berlin. This is where they saw each other for the last time.

Before he was sent to Belsen, Harold spent time at Neuengamme. In 1945 while being transferred to Belsen, he had to spend 5 days on a cattle truck. He was at Belsen for another 5 days, then finally the camp was liberated by British soldiers. Harold was 1 of 2 British men who survived Belsen concentration camp. Harold later testified in the Belsen trial where he gave evidence on how he was treated during his time there:

“I do not know if I shall succeed in giving you an idea of what life in Belsen was like on those last five days. I would like to point out that we suffered from, firstly, starvation, absolute starvation; secondly, complete lack of water for some six days; thirdly, lack of sleep, a few minutes sleep near the burial pits was occasionally possible; fourthly, to be covered with lice and delousing onself three or four times a day proving absolutely useless. If one sat inside the hut or outside in the yard one was covered within five or ten minutes. Then the fatalistic attitude among the prisoners towards what the end would certainly be – the crematorium or the pits.”

–Harold Le Druillenec, Belsen Trial.

The belsen trial was held in Luneberg in 1945 where 45 camp guards were accused of war crimes. Harold had to relive his terrible experience again after not being fully restored to health after his time spent there. Harold needed very serious hospital treatment after his experience at the camp.

“In the two previous camps there was an attempt made at cleanliness, although the atrocities or sadism in the other camps were worse than Belsen. I think I can fairly describe Belsen as probably the foulest and vilest spot that ever soiled the surface of this earth.”

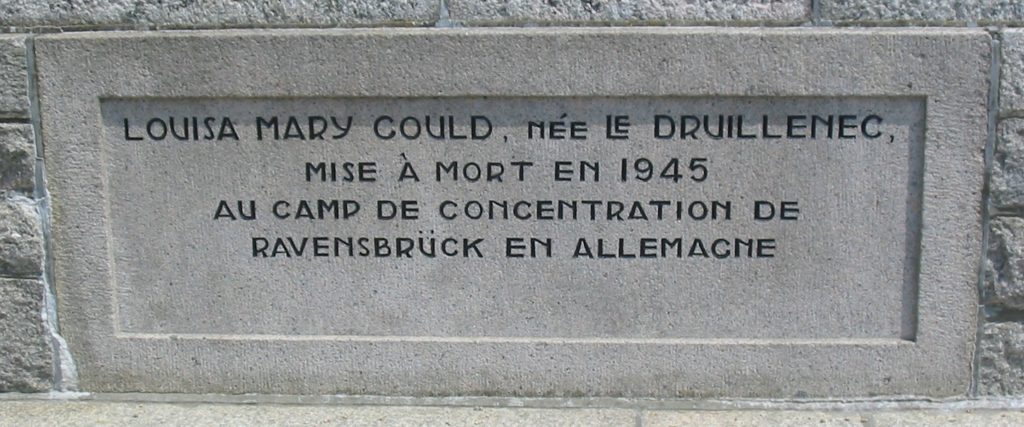

Harold’s sister Louisa fell ill soon after leaving Jersey, and was taken to the gas chamber in Ravensbruck in 1945 where she died.

The POW Feodor Burriy was never found by the Germans and continued to be sheltered by another islander Bob Le Sueur who in his 20s spent the last year of the war moving Feodor from hiding place to hiding place, along with 7 other POWs. The first time Bob went to Louisa’s house, she told him “Bill” was French, as she had taught him to speak English with a French accent, however it was clear to Bob that he was not actually French.

“One night Bill got so drunk he crouched down and started a Russian song and dance routine.”

Feodor was a talented artist, and sketched many pencil portraits during the 2 years he stayed with Louisa. Strict control in the soviet union meant that Feodor wasn’t able to contact Bob again until the 60s. They finally met each other again in 1992 when Bob travelled to Russia, after the USSR had collapsed meaning travel restrictions were not as strict. Feodor then returned to Jersey in 1995 for the 50th anniversary of Jersey’s liberation. 3 years later, he died at the age of 80.

“…he agreed to come and as the plane landed the pilot announced he was returning for the first time since 1945. All the passengers burst into applause.”

There was also a film made which is based on Harold, Louisa and Ivy’s story that was released in 2017. The script was written by Louisa Gould’s great niece, Jenny Lecoat. Bob Le Sueur also helped with the script. George Lawrie, who’s an extra in the film, is the great great grandson of Louisa Gould.

“It took a year to research it and two years before it was picked up”

“Having lost one of her sons serving in the Royal Navy, she explained to a friend, “I had to do something for another mother’s son.”

– Source