An archive is a collection of historical records or an actual place that they are located in. Archives contain documents which have been collected over a longitudinal period of time. These primary documents are then stored and used to showcase the function and or story of a particular person or organisation. Archives are used to allow us to gain a more in depth understanding of the historical factors at a particular moment in time, and act as a repertoire allowing us to reflect on the history of that specific place and time. Records stored within an archive is varied, from diaries, legal documents, financial documents to photographs and film. An archive can act as repositories of cultural memories of the past, as we are able to store reliable documents, which are memories of the past, which when we reflect on the documents will clearly show cultural memories. Although they are reliable, imagery is highly subjective which can lead to misinterpretation of the objects stored within an achive. Archival memory can be considered a social construct as they can show power of relationships in that society at that particular time in history.

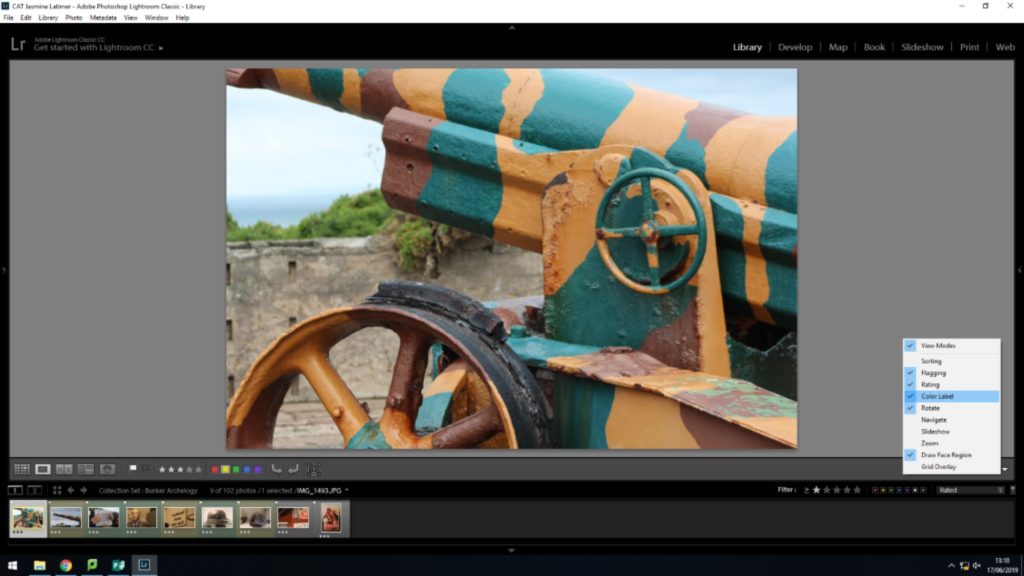

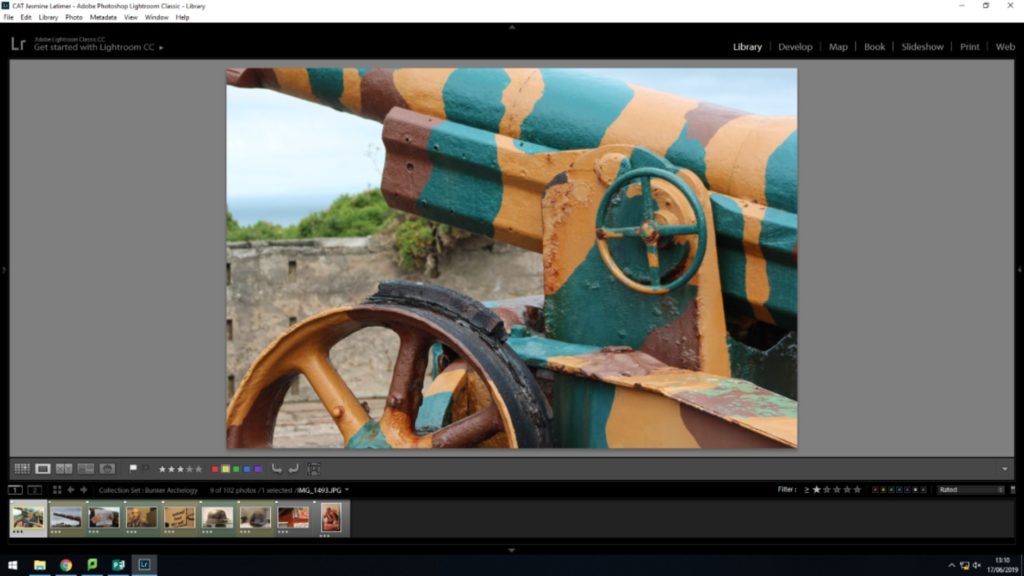

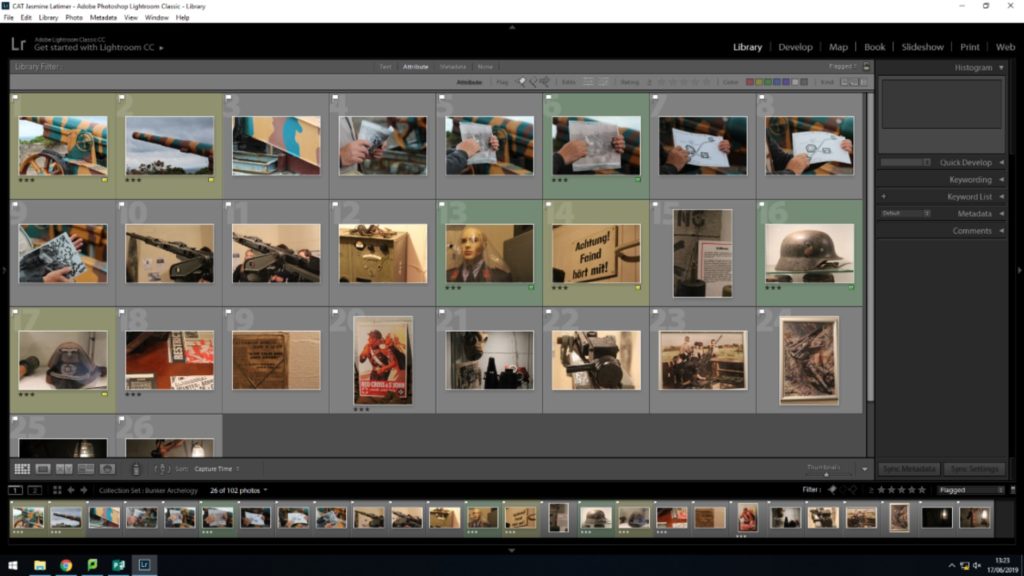

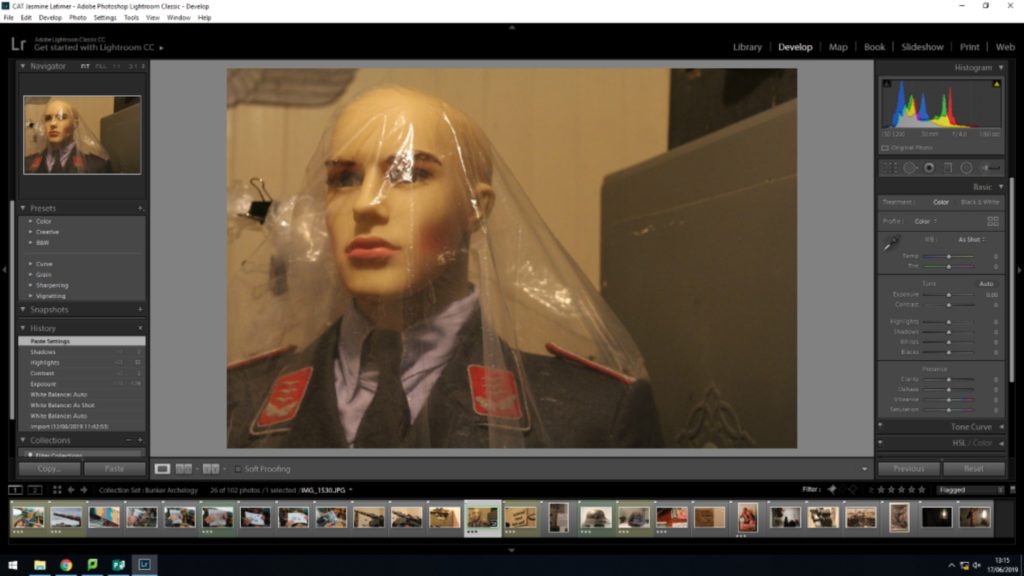

Photography can perform as a double role within an archive as it visually showcases the person or organisation. Photographs can be used for both scientific purposes (images which are precise and detailed photographs of industrial events and processes. These photos can be used for monitoring industrial processes and allows us to view and analyse the change in the process. Within an archive this scientific purpose is useful as it allows us to see how a process or industrial event has changed from an archival image compared to a recent image of the same thing, allowing us to visually see a clear change) and artistic purposes (images which allows us to visually see the historic and cultural elements of the time and place at which the photograph was taken at. These photographs can almost tell stories which gives us insight into what life is like in that image and allows the imagination of the viewer to explore and interpret the photograph in a unique way.) which showcases the double role, of scientific and artistic purpose, which photographs have within a photo archive.

David Bate’s text explains how museums often use archives and collections of artefacts in order to display and present a particular cultural and or historical moment in time. Museums creates historical narratives of culture and can act as a repository of memories.

At the beginning of the text it talked about the ‘British Museum’ in London and how they only employed the first photographer, Roger Fenton, in 1854. Fenton captured images of the museum’s interior showcasing the artefacts, the reason behind this was to showcase what these artefacts looked like in the Victorian era, showing change and the historical values of the museum. The text says “The pictures themselves create an atmospheric space, with a kind of silence around the artefacts, a stillness of the historical museum.” This implies that the objects are said to have an “aura”, suggested by Walter Benjamin, which created a historical distance, outlining the importance of the historical factors in relation to the object. Fenton’s arhived images are still famous and are featured in museums to showcase the artefacts.

Another key artist mentioned within the text is Tracey Moffatt, who painted the series ‘Something More’ in 1989. In this series the paintings present a “fictionalised biographical account of a young Aboriginal woman’s desire to leave her rural life in the city.” In these images the background holds blurred figures in the background which are starring at the woman located in the foreground, the difference in appearance of the people helps to showcase the story and cultural factors within the paintings. Needless to say, the majority of the stories end in violence and or death. It is said that Moffatt’s early work within the series where based on personal memories, which makes her work a personal archive of personal memories presenting historical factors of her past.

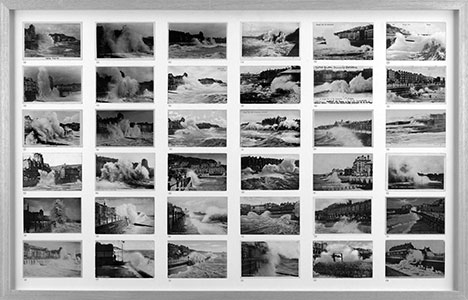

Another key artist mentioned is Susan Hiller, who created hundreds of postcards of waves crashing onto the coasts around Britain, each postcards is presented differently through the experimentation of tinting, black and white and painting them. The postcards are then arranged into a grid format, showcasing an archival of “how a culture sees itself”. It is said that all the images work well together creating a lyrical display, as our eyes go round the frame following the waves crashing. Although the piece can be tranquil, the natural force of the sea begins to suggest a different viewpoint of force and power, which creates a link yo an emotional threat by a hostile person or idea. These methods and attitudes makes Hiller’s work an anthropologist or cultural archivist.

In a recent documentary on the BBC, Dr Gil Pasternak researched the photographic history of what family photographs say about Britain’s post-war social history. Within this they looked at issues concerning social class, gender and cultural background which affect the production, use and perceived meaning of a family portrait. They also looked at how the internet is changing the way photo archives are stored and used. Family Narratives where mainly shown through photo albums which showcased how precious some of the stories and memories where to the family. An important phrase told by Dr Gil read “These examples demonstrate how the development in photographic technology combined with local social history influenced the types of photographs they were able to capture, and therefore also the stories they were able to tell about themselves, their family and friends, their beliefs, interests, aspirations, and life in the UK more broadly.” They also said “In the era of smart technologies, family photographs no longer merely function as memories of the past, but they instead become active participants in the formation of our present experiences and in shaping the dynamics of family life.” This quote summaries the conclusions of the research and how modern day is shaping society and photography.

With the world constantly changing, and the future looking to be solely reliant on technology, it begins to suggest how archives will change and adapt to meet the requirements of the future. Many people share there images through social media, from facebook to instagram, which creates an online storage/archive of that person’s past, which allows others to reflect on their past and presents that person’s narrative in life. Images are much easier to store this way and are more cost effective, compared to printing them out, and accessible to everyone making this an ideal way for people to achieve their past. A limitation to using modern technology to create archives is the issues of loosing images, or if a social media sight was to shut down, due to this it can lead to an incomplete of completely lost photo archive, making material harder to find and less reliable.

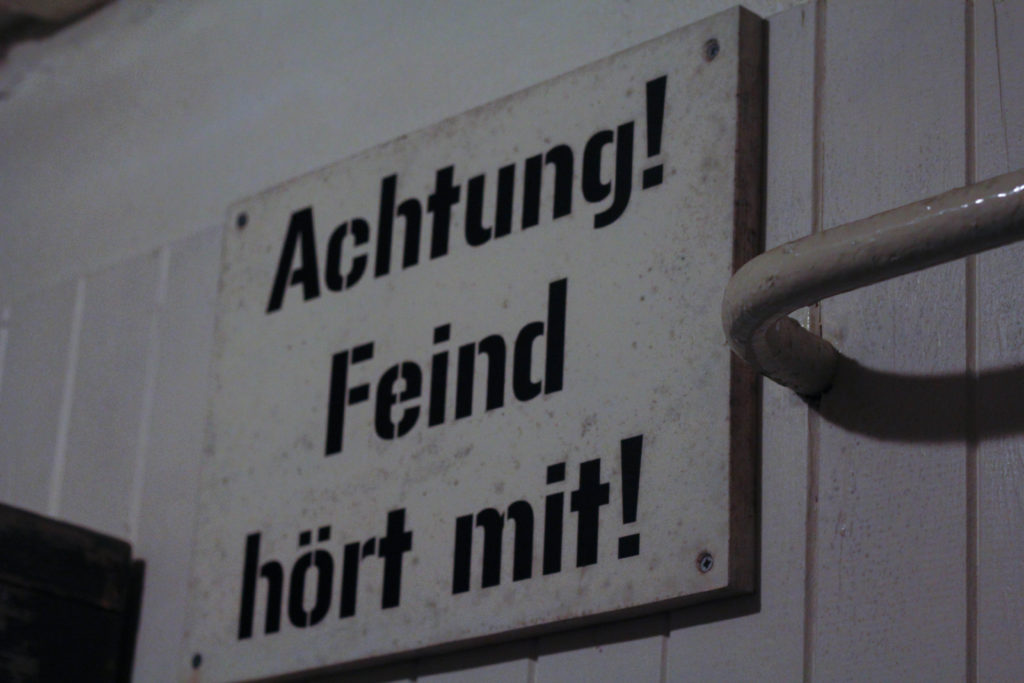

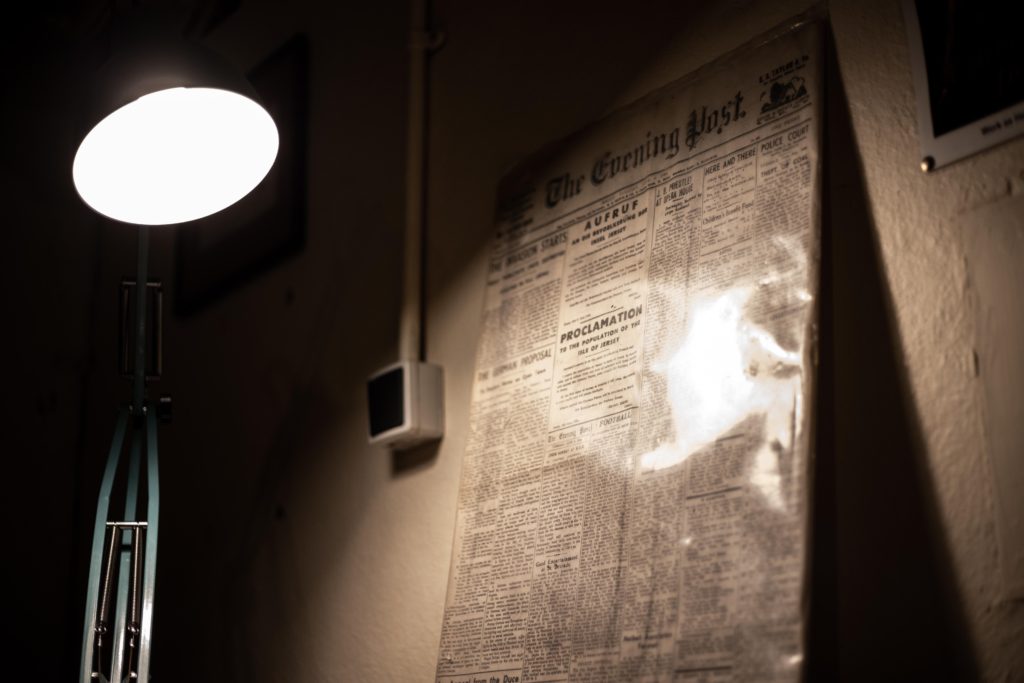

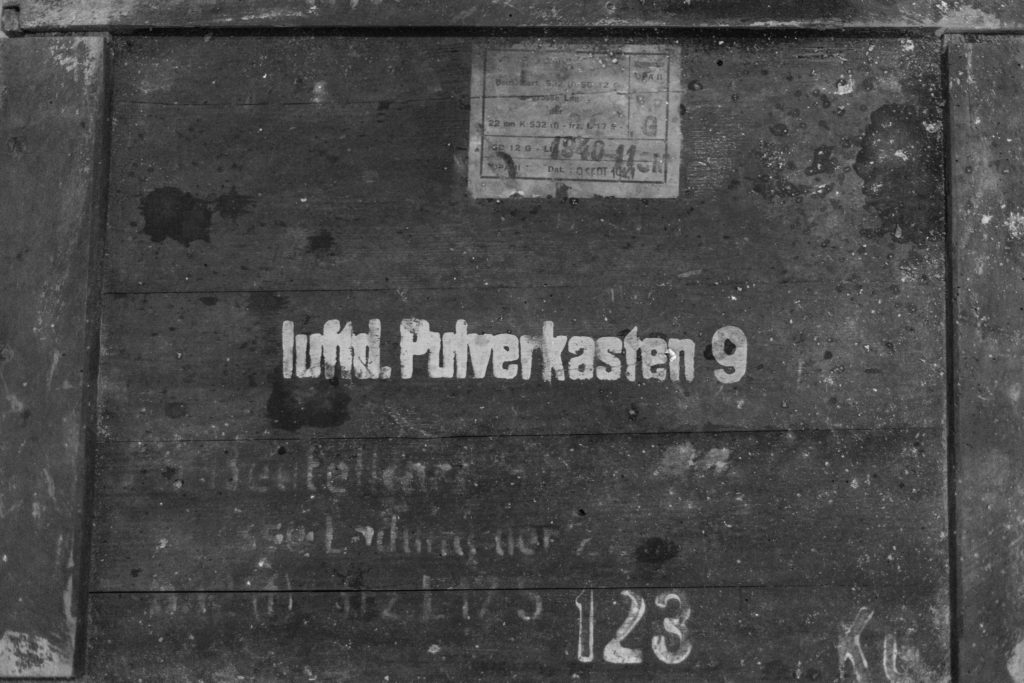

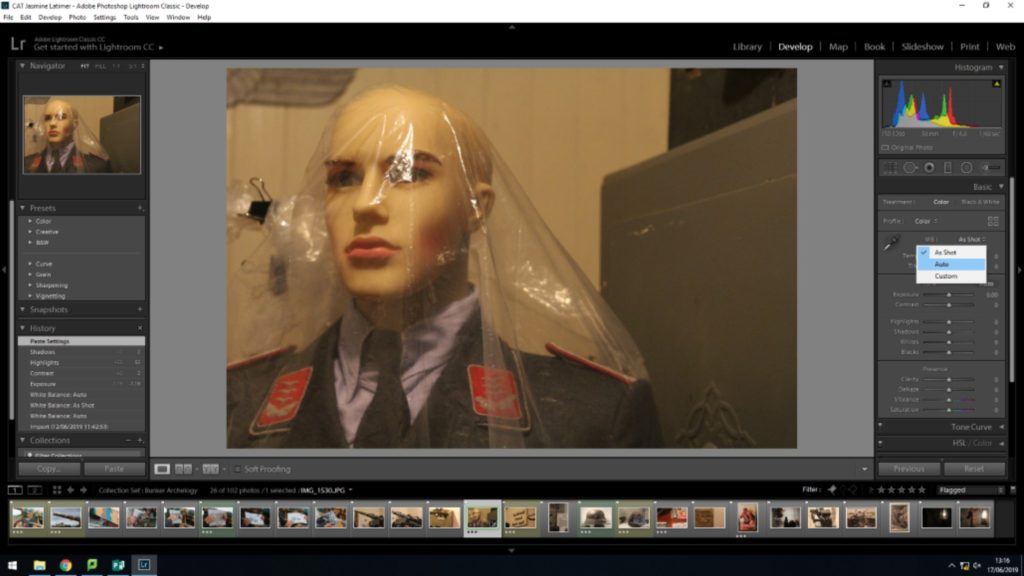

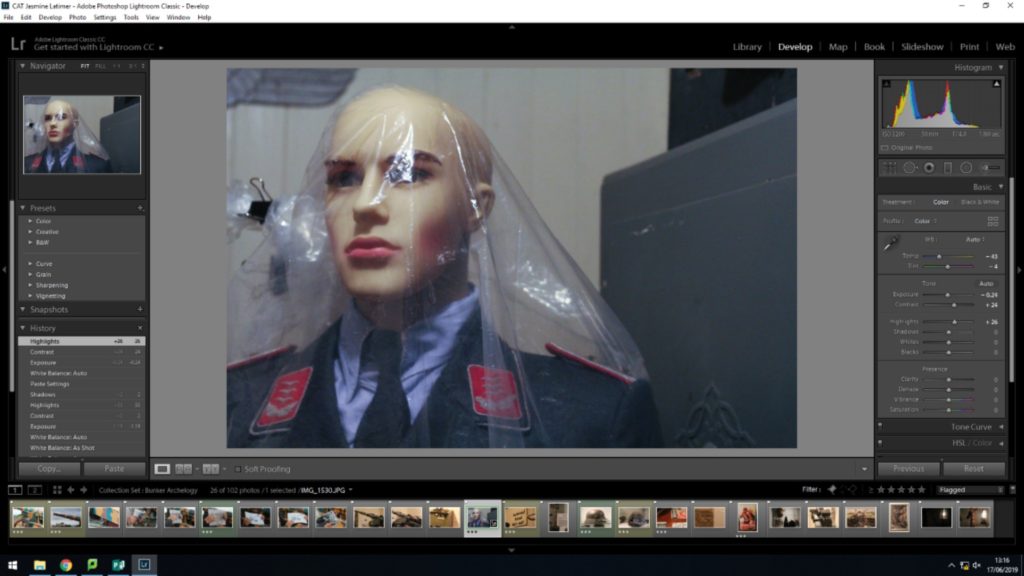

To conclude, an archive is a key tool for contemporary photographers. They provide historical/cultural narratives which gives us insight in what life was like at that time and place. The documents stored within an archive varies but all still help to present a specific memory and provides useful insight. Archival material can enrich my personal study as the material will gives me insight into historical and cultural elements of the second world war, which enables me to think more carefully about what I am capturing and allows meaning to be presented within the images. Moreover, the narrative of the images tells the story of the war and the different aspects which will allow me to explore the story and the different aspects, which will provide a more well rounded project. In addition, archival material will be useful when I want to explore the memories of others in order to present their stories and will provide useful historical facts and stimulus’ to help develop my idea and knowledge of the war. In Jersey we have an archive called “Societe Jersiaise” which is a photographic archive containing roughly 80,000 images dating from the 1840s to present day. Due to the resources available to me should lead to an in-depth research into Jersey’s Second World War. In addition, a photographic achieve is a valuable source for contemporary photographers because of the idea “the best art understands a history to anticipate a future.” It also allows photographers to look at interpreting history in a new way to reveal a subjective narrative.