Street Photography and Candid Photography

Street photography, also sometimes called Candid photography is photography conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents within public places. Although there is a difference between street and candid photography, it is usually subtle with most street photography being candid in nature and some candid photography being classifiable as street photography. Street photography does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment.

- when the subject is in motion,

- by avoiding prior preparation of the subject,

- by surprising the subject,

- by not distracting the subject during the process of taking photos.

Henri Cartier–Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004) was a French humanist photographer considered a master of candid photography, and an early user of 35mm film. He pioneered the genre of street photography, and viewed photography as capturing a decisive moment. Cartier-Bresson was one of the founding members of Magnum Photos in 1947.

Magnum Photos

In early 1947, Cartier-Bresson, with Robert Capa, David Seymour, William Vandivert and George Rodger founded Magnum Photos. Capa’s brainchild, Magnum was a cooperative picture agency owned by its members. The team split photo assignments among the members. Rodger, who had quit Life in London after covering World War II, would cover Africa and the Middle East. Chim, who spoke a variety of European languages, would work in Europe. Cartier-Bresson would be assigned to India and China.

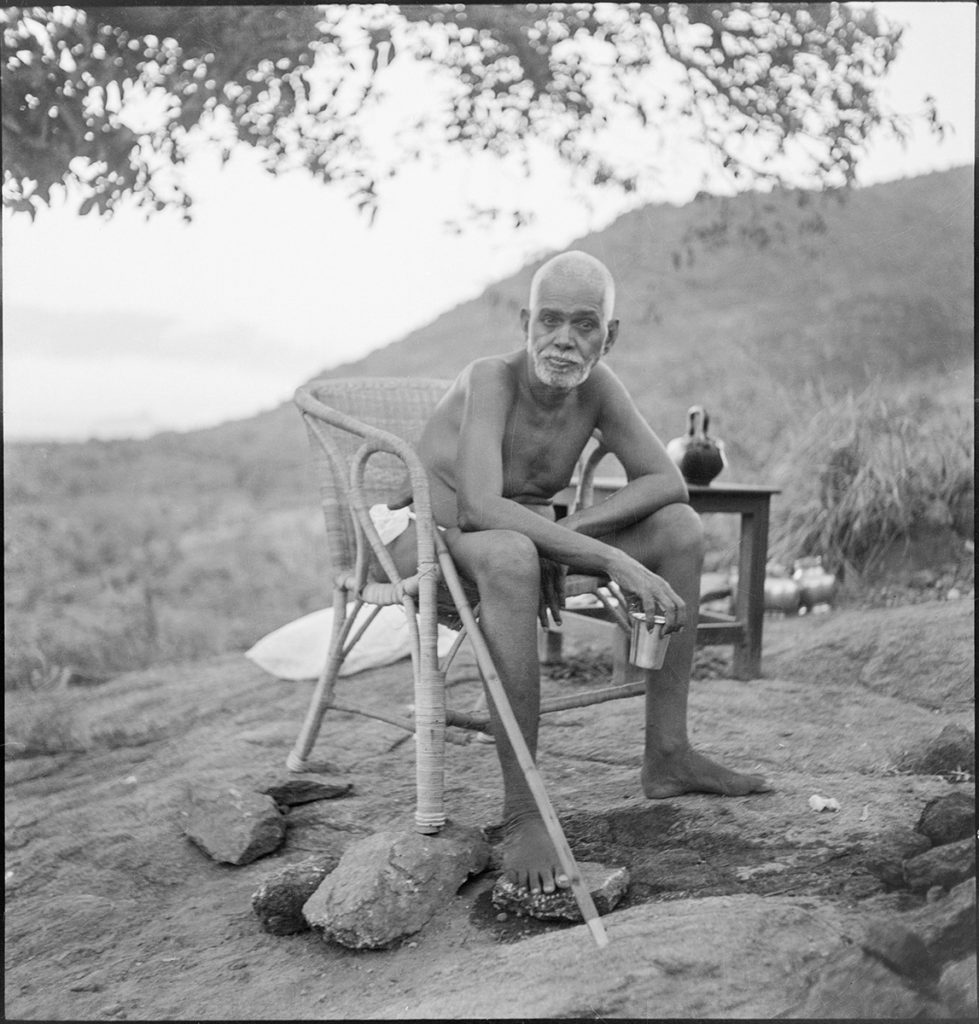

Cartier-Bresson achieved international recognition for his coverage of Gandhi’s funeral in India in 1948 and the last stage of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. He covered the last six months of the Kuomintang administration and the first six months of the Maoist People’s Republics. He also photographed the last surviving Imperial eunuchs in Beijing, as the city was falling to the communists. In Shanghai, he often worked in the company of photojournalist Sam Tata, whom Cartier-Bresson had previously befriended in Bombay. From China, he went on to Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), where he documented the gaining of independence from the Dutch. In 1950, Cartier-Bresson had traveled to the South India. He had visited Tiruvannamalai, a town in the Indian State of Tamil Nadu and photographed the last moments of Ramana Maharshi, Sri Ramana Ashram and it’s surroundings. A few days later he also visited and photographed Sri Aurobindo, Mother and Sri Aurobindo Ashram.

Magnum’s mission was to “feel the pulse” of the times and some of its first projects were People Live Everywhere, Youth of the World, Women of the World and The Child Generation. Magnum aimed to use photography in the service of humanity, and provided arresting, widely viewed images.

The Decisive Moment

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his book Images à la sauvette, whose English-language edition was titled The Decisive Moment, although the French language title actually translates as “images on the sly” or “hastily taken images”. Images à la sauvette included a portfolio of 126 of his photos from the East and the West.

Cartier-Bresson took his keynote text from the 17th century Cardinal de Retz, “Il n’y a rien dans ce monde qui n’ait un moment decisif” (“There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment”). Cartier-Bresson applied this to his photographic style. He said: “To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.”

Analysis

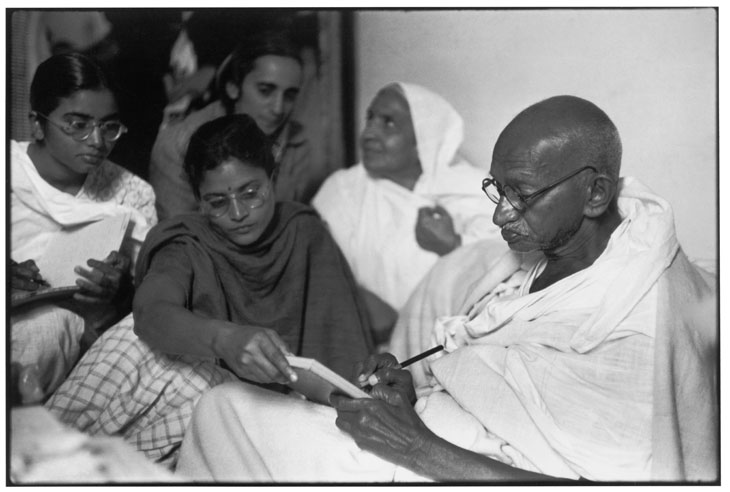

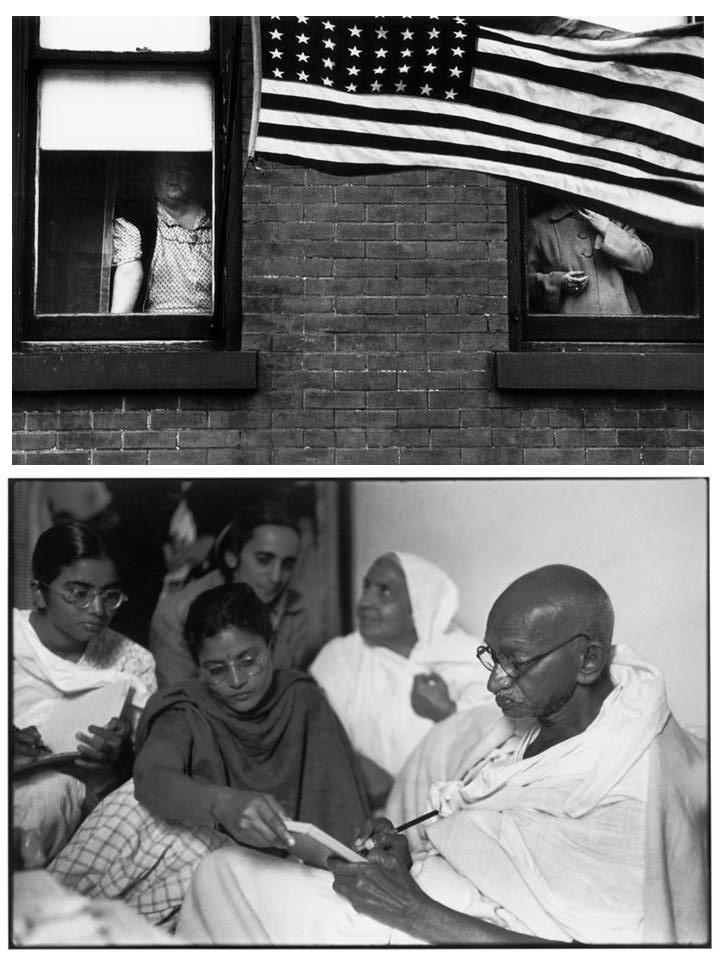

Technical: There seems to be the use of natural lighting in this photograph there is no harsh lights which gives off the impression that it is the natural lighting in the room which is giving the photograph the light. There is a strong focus in the foreground of the photograph where Gandhi himself is seated and then towards the background of the photograph it becomes a little less focused but there is also a strong sense of depth and you can see the layers in the image as there is a clear foreground, mid ground and background creating perspective and a sense of depth.

Visual Elements: Visually there is a lot of tone throughout the image it is lighter and brighter towards the front of the image and in the background there is a lot more dark tones created by the shadows and gives a contrast in the photograph, as it is lighter in the front of the photograph compared to the back it also helps us understand that the light source would be coming front behind the camera and looking on at the scene. Our eyes are easily lead through this photograph as they move from one person easily to the next and this creates a leading line as it leads us towards the back end point of the photograph.

Context/ Concept: The photograph shows Gandhi dictating a message at Birla House, the residence where he spent his last days and in which he was assassinated, just before breaking his fast. Delhi, India. 1948. Cartier-Bresson initially set out to create a photographic essay that would capture the essence of the country, its past and present at a time of rapid social change. India’s recent independence from Britain had quickly deteriorated into unrest with the dividing of the country into Hindu India and Muslim East and West Pakistan. At the centre of these upheavals was Mahatma Gandhi, who, after campaigning for India’s independence, was now protesting for the end of the violence between Hindus and Muslims. Cartier-Bresson had exclusive access to Gandhi, recording the activist’s hunger strike in protest of riots in which millions died. However, with the assassination of Gandhi on January 30, 1948, the day after he had taken his portrait, he unexpectedly found himself witness to a major historical event.

Emotional Response: My initial emotional response to this photograph is that it is quite a light photograph creating it to seem almost uplifting in a way.

Comparison to other Photographers

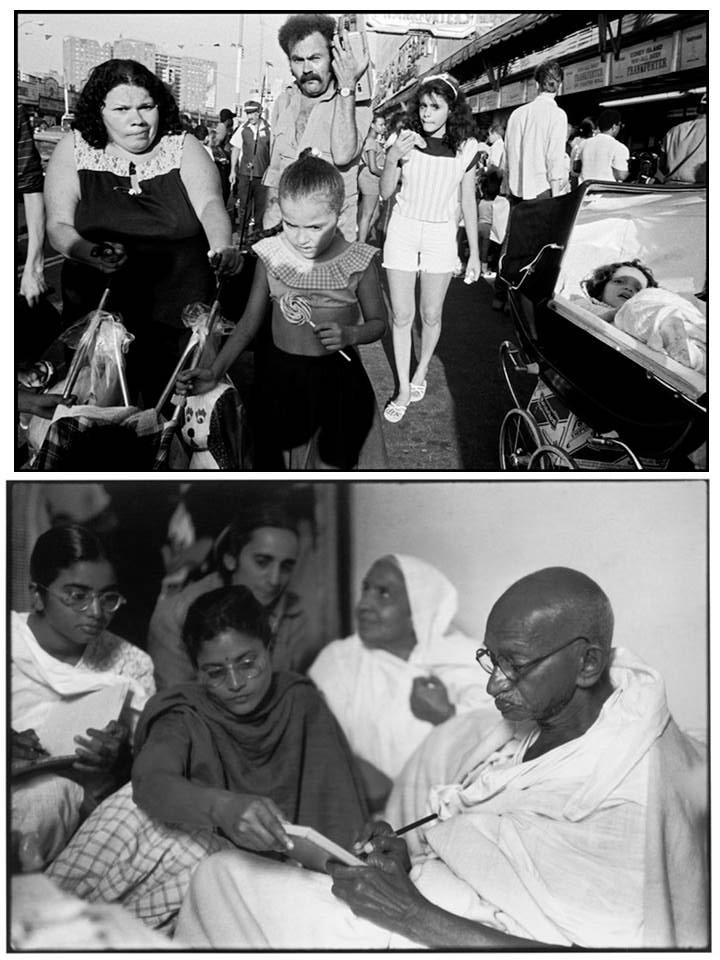

Bruce Gilden

-Bruce Gilden

Bruce Gilden (born 1946) is an American street photographer. He is best known for his candid close-up photographs of people on the streets of New York City, using a flashgun. He has had numerous books of his work published, has received the European Publishers Award for Photography and is a Guggenheim Fellow. Gilden has been a member of Magnum Photos since 1998.

Bruce Gilden was fascinated with people on the street and the idea of visual-spontaneity. His work is characterized by his use of flash photography and he has mostly worked in black and white, but began shooting in digital and colour when he was introduced to the Leica S camera as part of Magnums’s Postcard’s from America Project.

Both Henri Cartier-Bresson and Bruce Gilden produce documentary photography, however in two different styles and ways. Bruce Gilden is very extreme in the way he takes his photographs by using a flashgun and creates very up-close portraits of the general public and people on the streets in busy urban areas such as Brooklyn, New York. Neither of the photographers went into a lot of effort to alter the moment that they were capturing they wanted to document it raw and as it was however Bruce Gilden was a lot more intense and extreme with the way he took his photographs getting up close to the people very quickly and for a short span of time. Henri Cartier-Bresson, however, played a more subtle approach and captured the moments either from the side of the scene or mixed in the crowds that were on-looking. Technically, Gilden’s work seem to contain more contrast due to him using the flashgun as he works, Gilden’s photographs seem to be more busy and have more noise compared to some of Cartier-Bresson’s work.

Robert Frank

“When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.”

―

Robert Frank (born 1924) is a Swiss-American photographer and documentary film maker. His most notable work, the 1958 book titled The Americans, earned Frank comparisons to a modern-day de Tocqueville for his fresh and nuanced outsider’s view of American society. The Americans reveal Frank’s mature style, which is characterized by bold composition and ironic, sometimes bitter, social commentary.

Frank became associated with the so-called ‘Beat Circle’, a group of poets, writers and artists – beatniks – who exemplified the apolitical, free-form spirit of post-war American existentialism. Having made his living as a commissioned commercial photographer, but left feeling frustrated artistically in that role, Frank took his 35mm camera onto the streets and highways of America where he honed his highly influential style of wandering, observational photography. Frank shunned the principle of balanced compositions in favor of crooked, grainy high contrasts in black and white and his revolutionary approach to his subjects was to prove decisive in the development of a more authentic reportage photography.

Both Frank and Cartier-Bresson use their photography to document moments and people lives. Frank wanted to be both intuitive and ‘somehow engaged’ and his goal was to capture through his lens the way in which the environment had effected him on a personal level. Rather than capturing the environment effecting him on a personal level Cartier-Bresson felt his camera was and extension of his eye and wanted to capture visually stimulating material and he could linger for hours observing waiting for the perfect moment. In this aspect both Frank and Cartier-Bresson are similar in what they might look for but their work is also similar in the way it presents itself, both of their works hold a lot of tone, some of Franks tend to be on the darker toned side compared to Cartier-Bresson.