Albert Renger-Patzsch

Albert Renger-Patzsch, born on June 22, 1897 was a German photographer who was heavily associated with the New Objectivity. Renger-Patzsch was born in Würzburg, Germany, and began taking photographs by the age of twelve. After military service in the First World War he studied chemistry at Dresden Technical College. In the early 1920s he worked as a press photographer for the Chicago Tribune before becoming a freelancer. In 1925, publishing a book, the choir stalls of Cappenberg. He had his first museum exhibition in 1927.

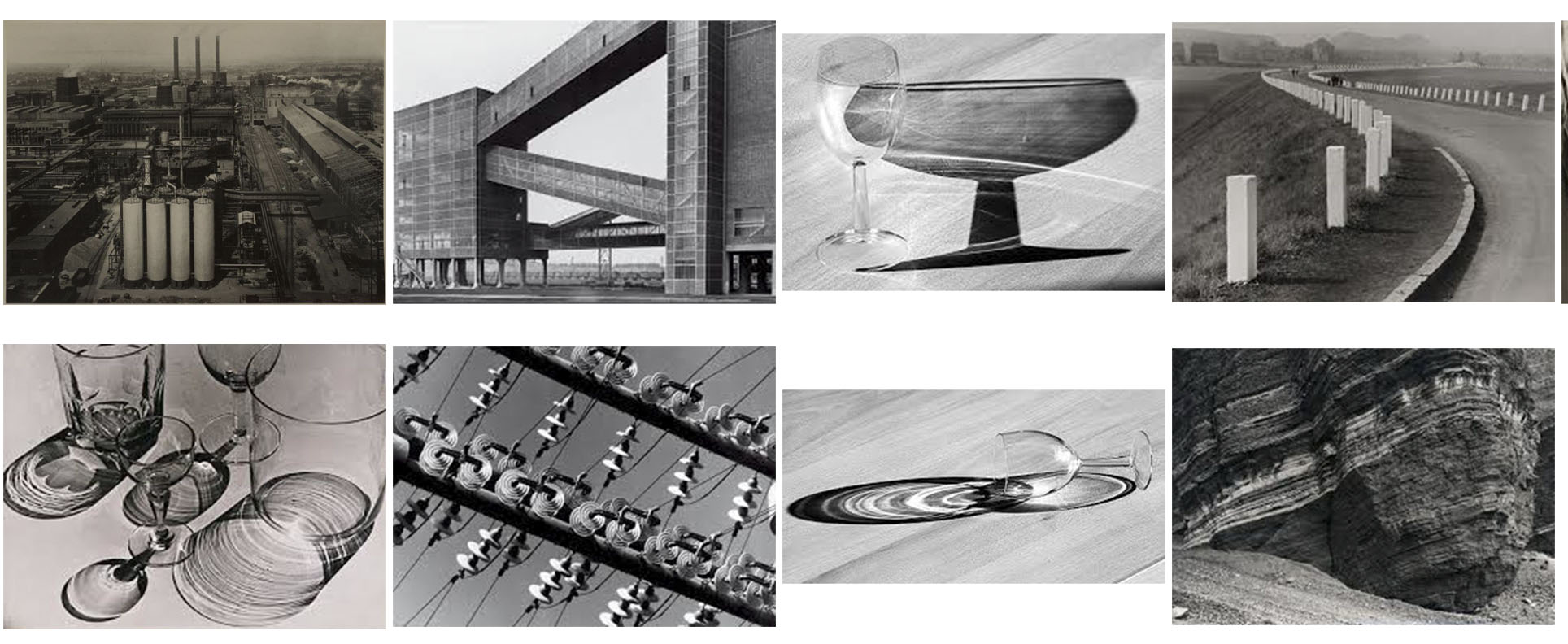

A second book followed in 1928, Die Welt ist schön (The World is Beautiful). This, his best-known book, is a collection of one hundred of his photographs in which natural forms, industrial subjects and mass-produced objects are presented with the clarity of scientific illustrations, the intent being to create beautiful photographs out of everyday items. The book’s title was chosen by his publisher; Renger-Patzsch’s preferred title for the collection was Die Dinge.

In its sharply focused on the newly emerging style of the time, The New Objectivity that flourished in the arts in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Like Edward Weston in the United States, Renger-Patzsch believed that the value of photography was in being able to capture the world in a way which displays all the textures and feelings that come along with it, and to represent the essence of an object. He wrote: “The secret of a good photograph—which, like a work of art, can have aesthetic qualities—is its realism … Let us therefore leave art to artists and endeavour to create, with the means peculiar to photography and without borrowing from art, photographs which will last because of their photographic qualities.”

Patzsch preferred to photograph items over people, focusing mainly on very ordinary everyday items but captured in a way which makes them extraordinary. A lot of his work also focuses on pattern and rhythm. The plants he photographs are often geometric and contain a lot regular pattern.

Among his works of the 1920s are Echeoeria (1922) and Viper’s Head. During the 1930s Renger-Patzsch made photographs for industry and advertising. His archives were destroyed during the Second World War. In 1944 he moved to Wamel, Möhnesee, where he lived the rest of his life.

ANALYSIS OF HIS WORK:

I have chosen and compare and analyse these two photos from Albert Renger-Patzsch’s work. Both of these photos include the presence of organic items, plants in this instance. Both have very clear and geometric shapes, with repeating patterns of forms. The focal point of the dandelion flower is the round and even tip of the stem, from which a repeating pattern of seeds come from. On the other hand, the image on the right lacks any noticeable focal point. Both images are very dramatic in nature, with deep and dark shadows being cast from the shapes of the two plants. The image on the right is very exposed, and the highlights are very strong, whereas the image on the left has more subtle highlights having an overall dark tone all-round. The image on the left has a deeper field of view through the use of the dark backdrop, whereas the image of the right lacks this as the light and over exposed backdrop shirks the depth of view. The overall undertone of the image on the left is warm and yellow, and the image on the right is a lot cooler with blue based undertones. Both images have been captured in portrait, unusual yet different and effective for this type of imagery.

MY FAVORITE IMAGES:

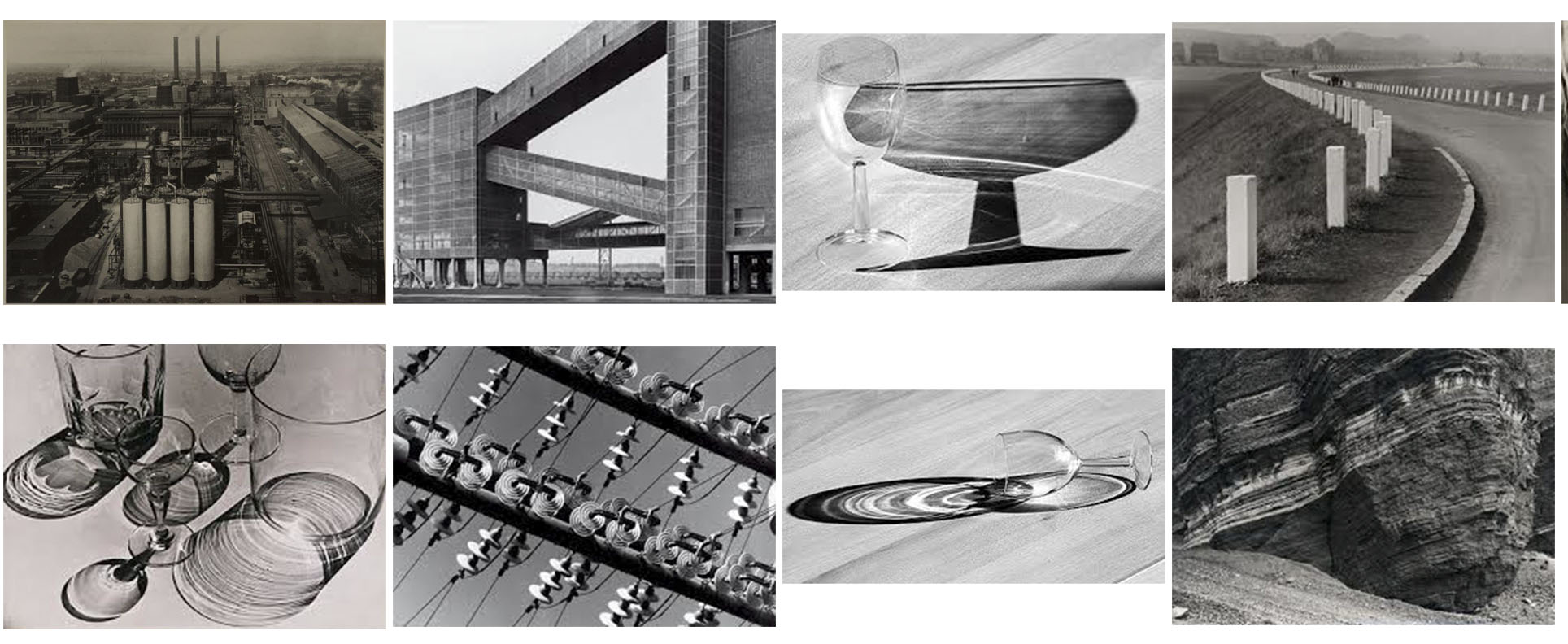

This is a collection of my favorite Albert RengerPatzsch work.

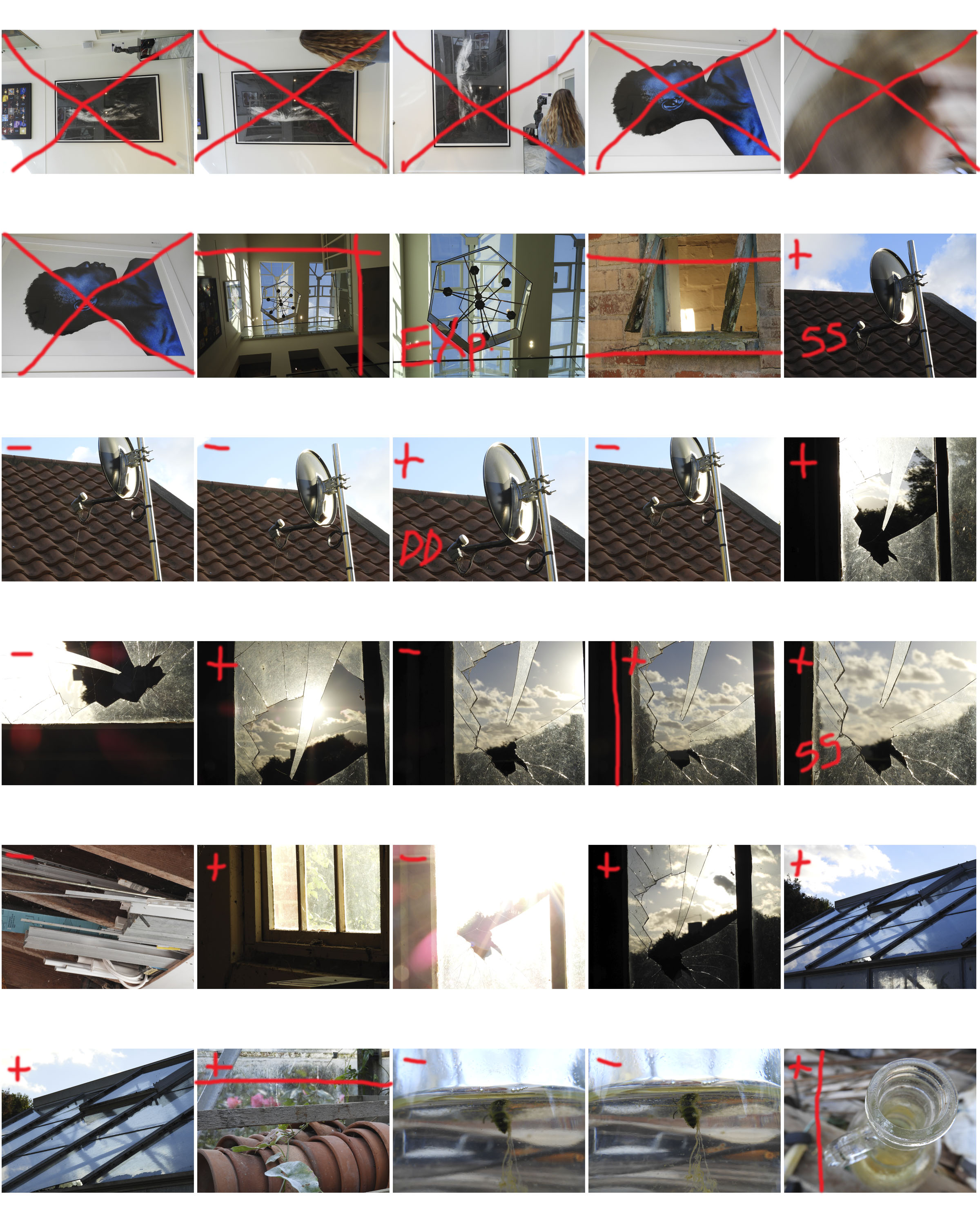

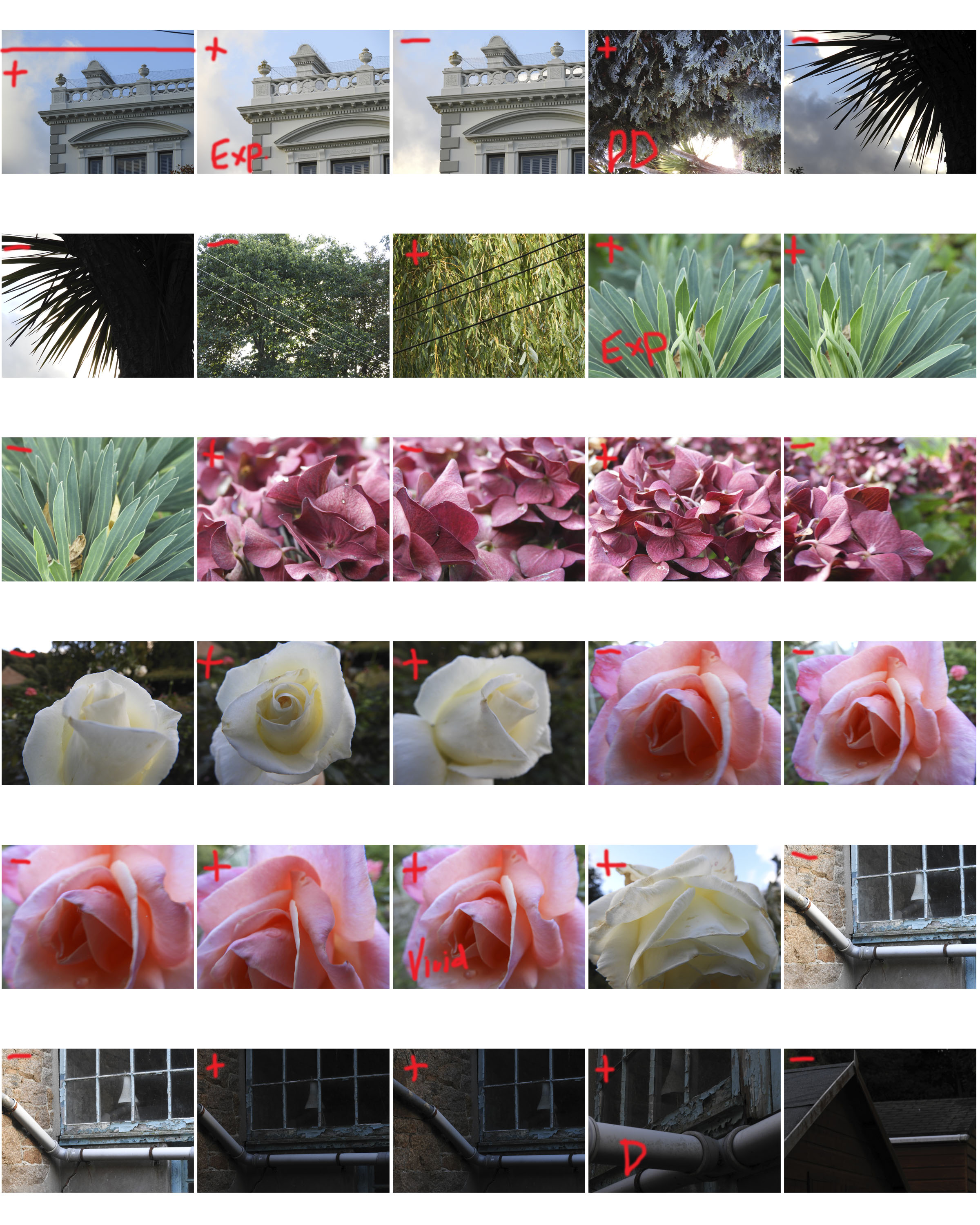

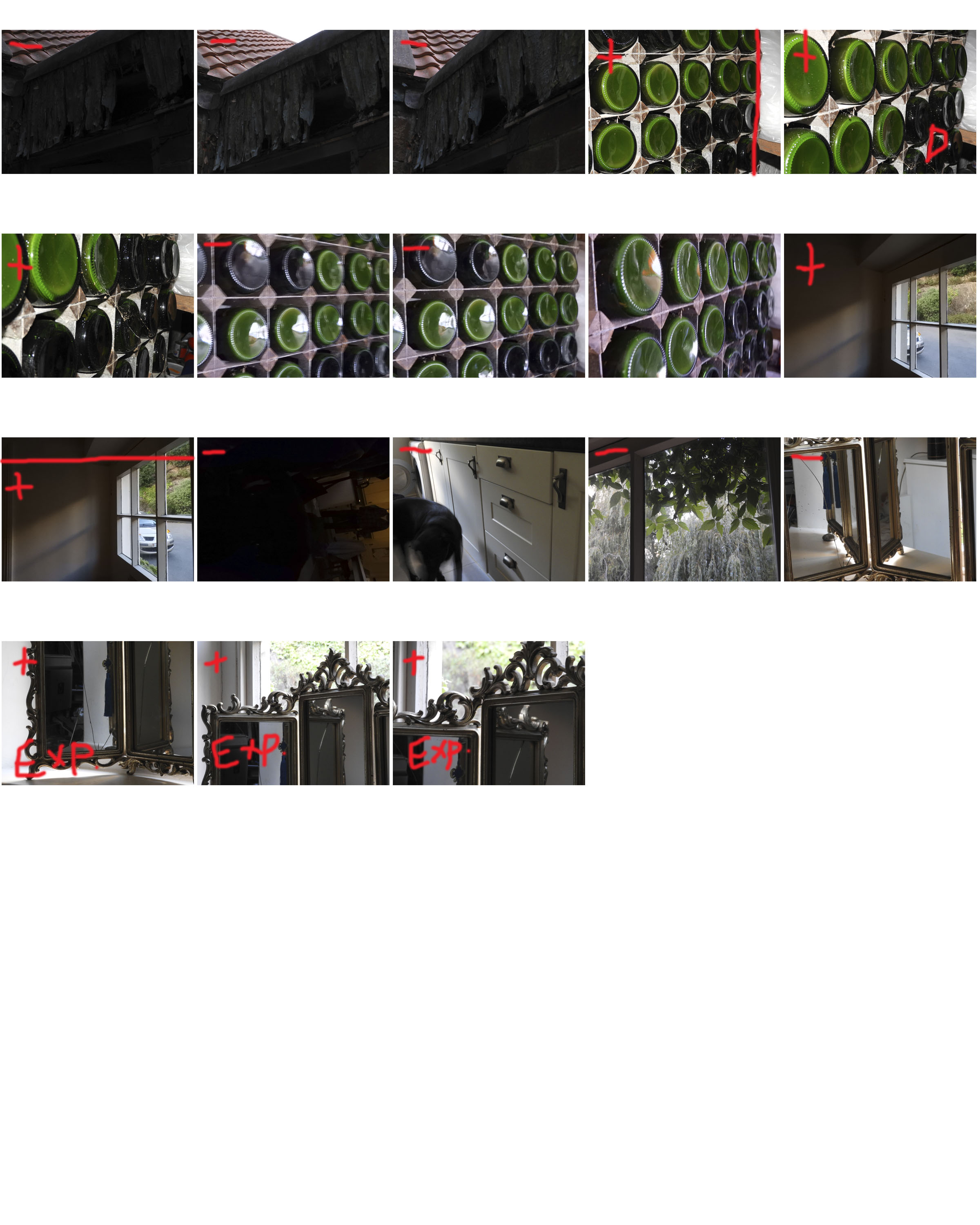

RESPONSE AND CONTACT SHEETS OF MY OWN WORK:

This is my response of Patzsch’s work in the form of contact sheets. like Patzsch, I focused on capturing very simple, everyday objects in a way that is beautiful and impressive. I experimented with light, changing the ISO settings on my camera and shutter speed, in order to capture images that are interesting and detailed. I found myself to often be using the macro setting on my camera when capturing up close photographs of plants, this allowed me to have clear and crisp photos that illustrated the detailed line work in the plants.