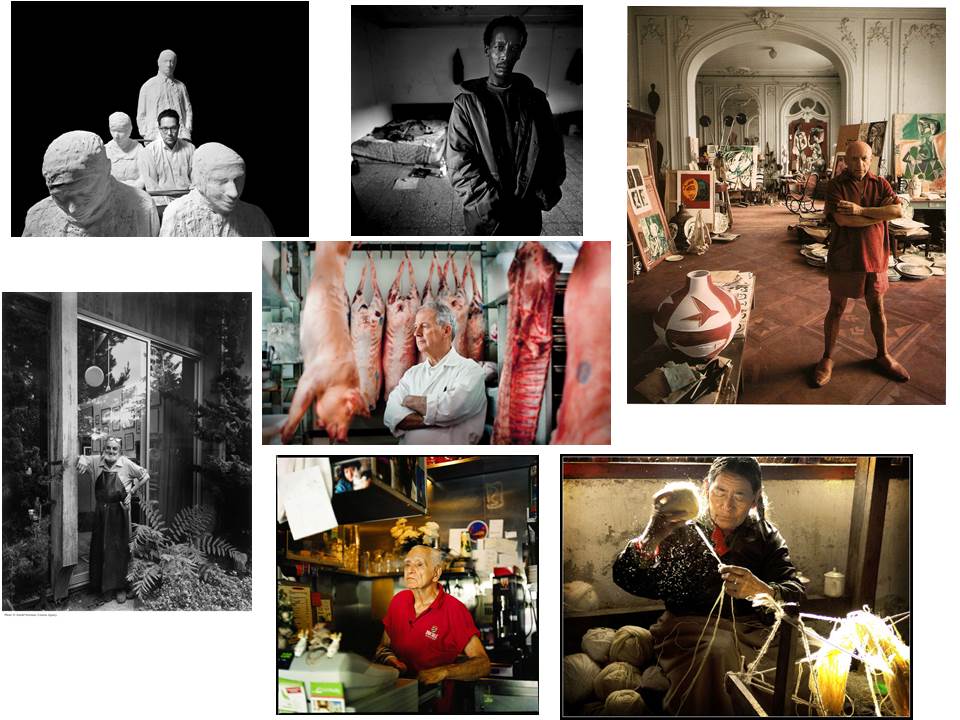

Arnold Newman is generally acknowledged as the pioneer of the environmental portrait, he is also known for his still life and abstract photography, and he is considered as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th Century.

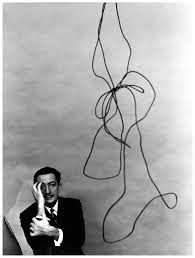

Newman found his vision in the empathy he felt for artists and their work. Although he photographed many personalities, he maintained that even if the subject is not known, or is already forgotten, the photograph itself must still excite and interest the viewer.

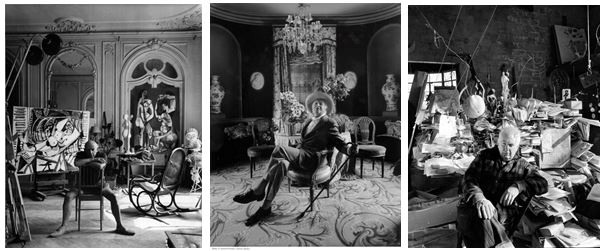

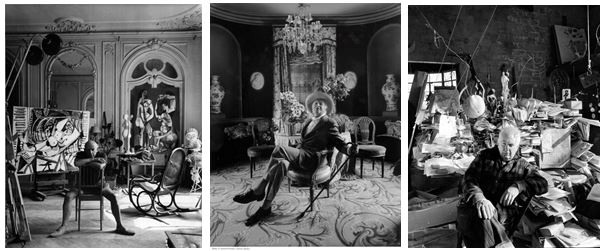

Newman normally captured his subjects in their most familiar surroundings with representative visual elements showing their professions and personalities

Newman normally captured his subjects in their most familiar surroundings with representative visual elements showing their professions and personalities

“I didn’t just want to make a photograph with some things in the background, the surroundings had to add to the composition and the understanding of the person. No matter who the subject was, it had to be an interesting photograph. Just to simply do a portrait of a famous person doesn’t mean a thing.”

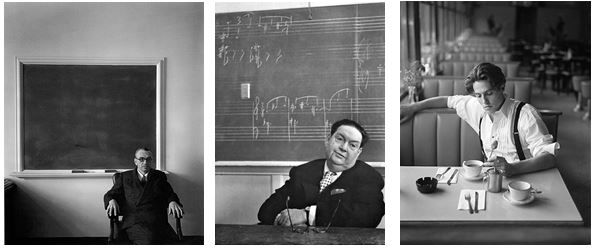

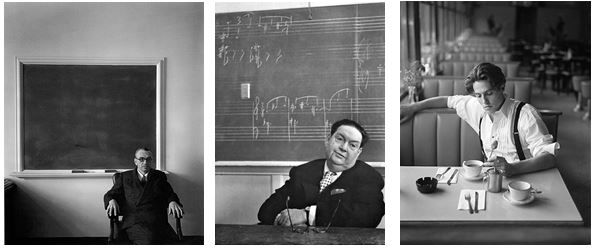

Newman’s best-known images were in black and white, although he often photographed in color. This image was photographed in 1946 and is a black and white portrait of Igor Stravinsky seated at a grand piano which became his signature image, even though it was rejected by Harper’s Bazaar, the magazine that gave the assignment to Newman.

Perhaps his most celebrated image is a 1946 portrait of the composer Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky, his expression deeply serious, is confined to the bottom left corner of the picture, cropped to his head and shoulders, an elbow resting on the piano, his hand supporting his head. The rest of the photograph is taken up by the raised lid of a large grand piano, strategically silhouetted against a blank wall, which is divided off-center into a gray and white rectangle. The lid forms the reversed shape of a leaning, abstract musical note.

He was one of the few photographers allowed to make a portrait of the famously camera-shy Henri Cartier-Bresson.

He was one of the few photographers allowed to make a portrait of the famously camera-shy Henri Cartier-Bresson.

One of the most famous was this sinister picture of the German industrialist Alfried Krupp, taken for Newsweek in 1963. Krupp is smirking, his fingers clasped as he confronts the viewer against the background of a assembly line in the Ruhr. In the color version his face has a greenish cast. The impression it leaves was no accident: Newman knew that Krupp had used slave labor in his factories during the Nazi reign and that he had been imprisoned after World War II for his central role in Hitler’s war machine.

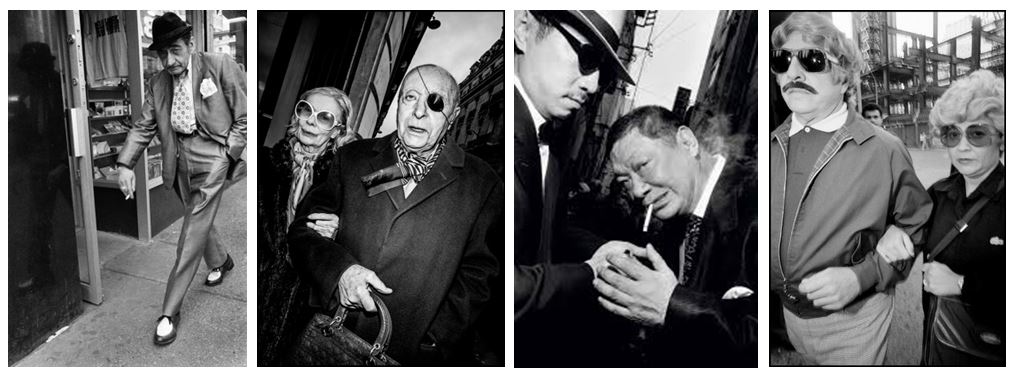

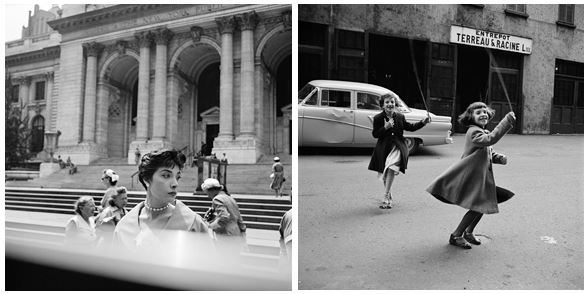

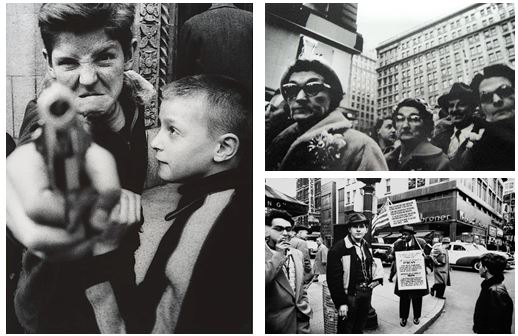

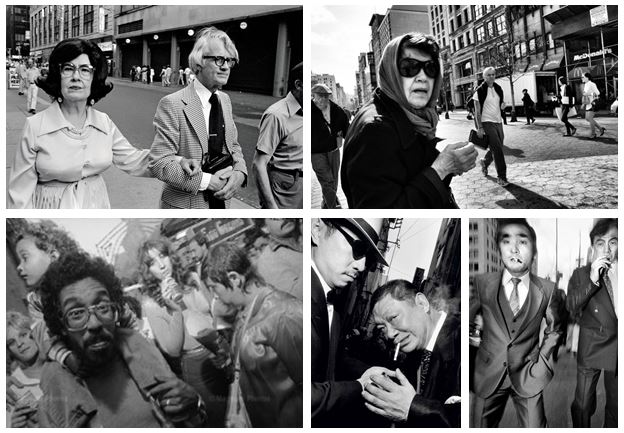

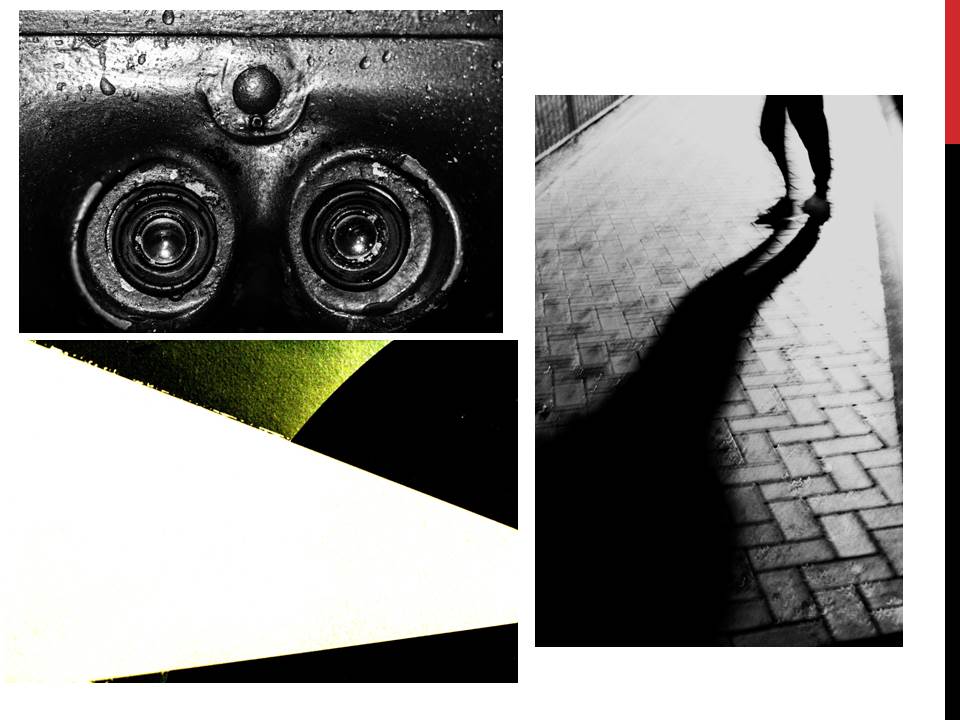

Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public, thereby also recording people’s history, but does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment.

Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public, thereby also recording people’s history, but does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment.

Newman normally captured his subjects in their most familiar surroundings with representative visual elements showing their professions and personalities

Newman normally captured his subjects in their most familiar surroundings with representative visual elements showing their professions and personalities

He was one of the few photographers allowed to make a portrait of the famously camera-shy Henri Cartier-Bresson.

He was one of the few photographers allowed to make a portrait of the famously camera-shy Henri Cartier-Bresson.

The subject will be more at ease, and so be more conducive to expressing themselves, as opposed to in a studio, which can be a rather intimidating and artificial experience

The subject will be more at ease, and so be more conducive to expressing themselves, as opposed to in a studio, which can be a rather intimidating and artificial experience

Within environmental portraits the subject tends to have a relaxed and calm face, in order to create an effect inside the image itself, whilst allowing the image to be emphasized due to its dramatic characteristics.

Sally Mann tended to focus on a individual face within her images, to really make out the backgrounds of the character within, allowing us to see the conditions many of the subjects were brought up in.

Within environmental portraits the subject tends to have a relaxed and calm face, in order to create an effect inside the image itself, whilst allowing the image to be emphasized due to its dramatic characteristics.

Sally Mann tended to focus on a individual face within her images, to really make out the backgrounds of the character within, allowing us to see the conditions many of the subjects were brought up in.

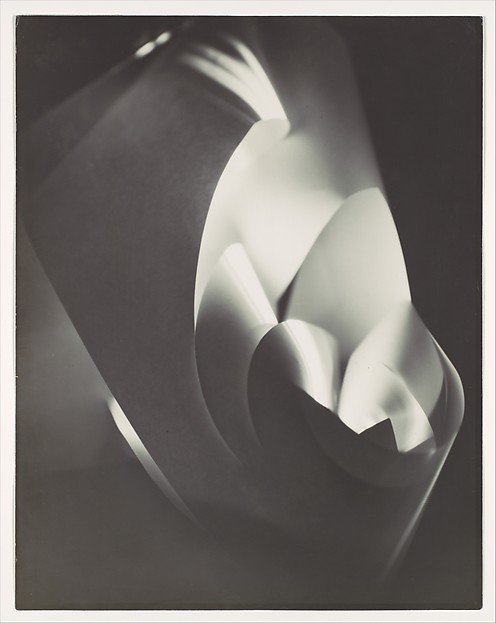

This enables a clear definition between the lights and darks to the photo, whilst it being very simplistic at heart, the scrunched effect makes an almost complicated look to the image.

This allows us to experiment as a photographer with not only composition but in a way our artistic creativity as well, due to how we are able to warp the materials given to form structures which we are able to use to our advantage.

This enables a clear definition between the lights and darks to the photo, whilst it being very simplistic at heart, the scrunched effect makes an almost complicated look to the image.

This allows us to experiment as a photographer with not only composition but in a way our artistic creativity as well, due to how we are able to warp the materials given to form structures which we are able to use to our advantage.