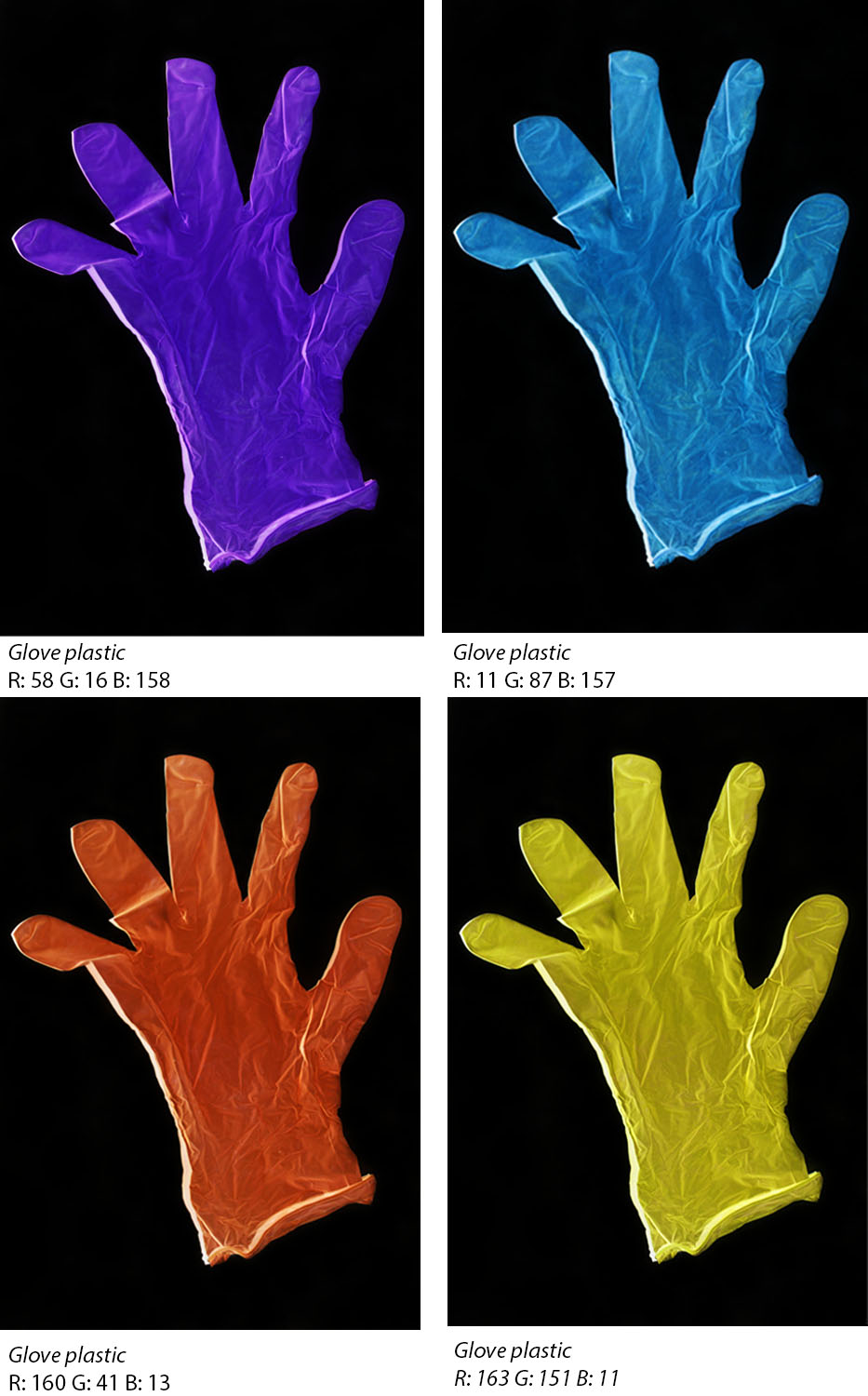

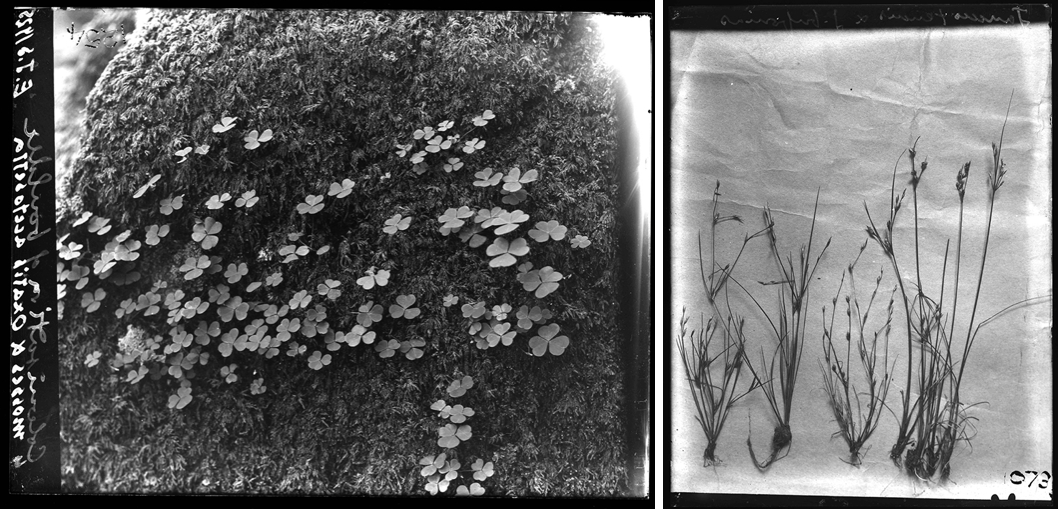

Chrystel’s “Plant Portraits or Weeds & Aliens Studies” is inspired by Edward Salisbury’s approach of documenting species. Lebas takes each plant directly placing it onto colour photographic paper in a darkroom under an enlarger light. She alters the colour of filtration on the enlarger in turn changing the way that the species appears on the paper. Each filtration value and exposure time is annotated alongside the photogram.

Plant Portraits or Weeds & Aliens Studies, 2013-

Pictured above is the species, Fallopia japonica (commonly known as Japanese Knotweed). She chose this species as Salisbury had previously carried out extensive research described in his book, Weeds and Aliens. The species is illegal to plant and come into contact with in the UK. Yet originally this plant was brought over as an exotic import. The shifting of meaning and classification over time fascinated Lebas becoming a thread of her new work.

“For most of history the only criterion by which human beings judged other species was their usefulness but,

in recent centuries, other dimensions became important so that certain species came to be valued for their attractiveness, their novelty or their

potential for game sport.”

– Charles Warren (2009), Managing Scotland’s Environment

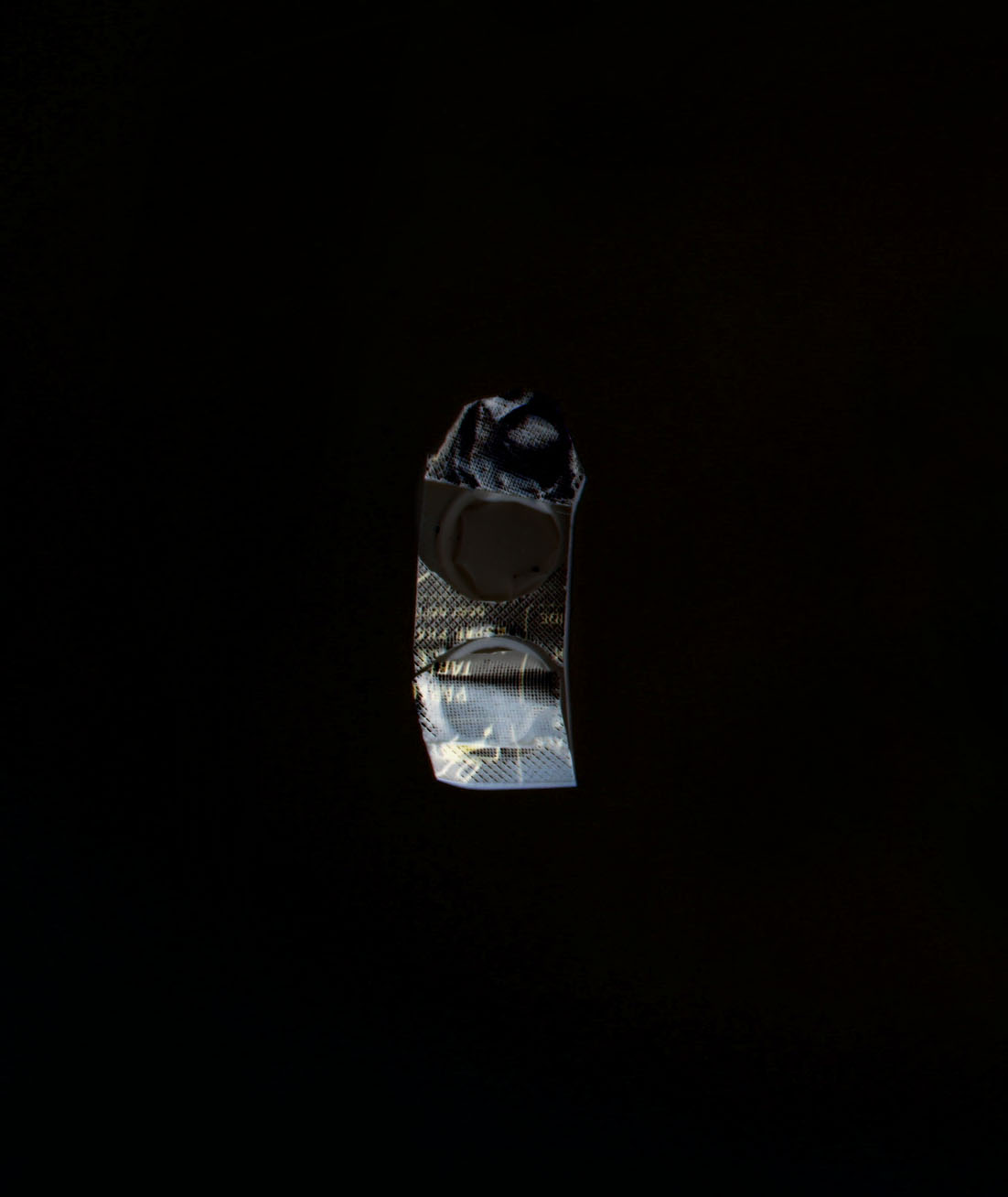

Similarly, Animated Nature uses similar techniques of placing species onto photographic paper in this case to form photograms of bird silhouettes.

Animated Nature, 2009, Unique Chromogenic photograms, 40 x 50 cm

Image Analysis

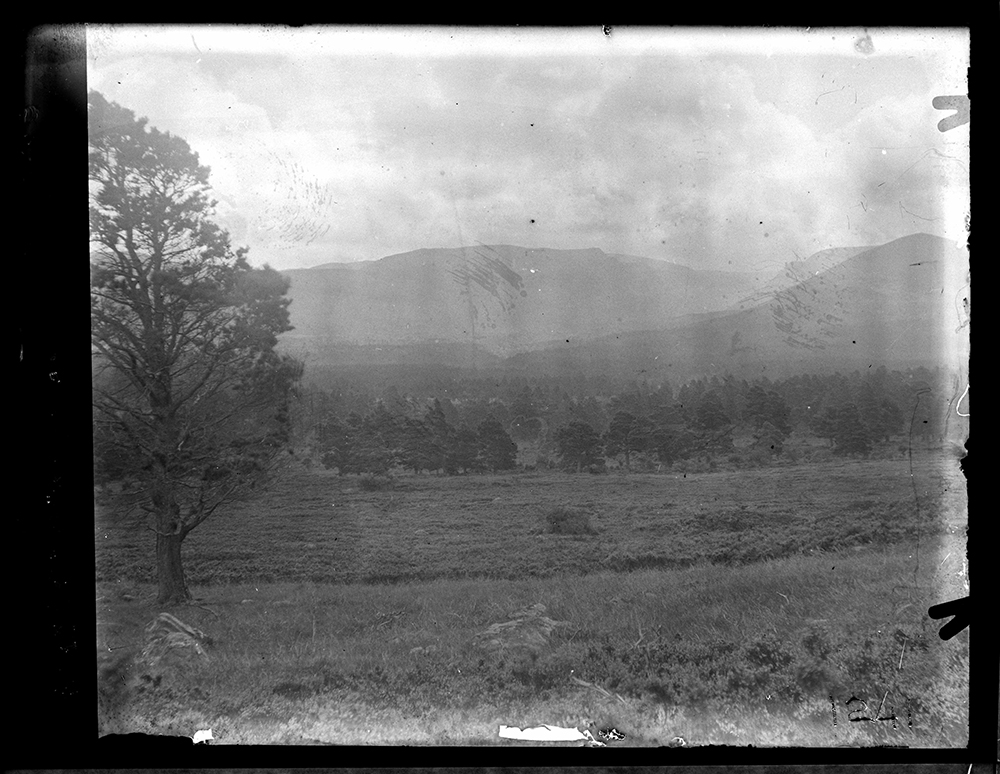

Between about 1907 and 1938, armed with a camera and a notebook, Edward Salisbury worked in four geographical areas: Arrochar, in Argyll and Bute, south-west Scotland; Rothiemurchus Forest, an estate in the Highlands near Aviemore; Culbin Sands, a long spit of sand along the southern shore of the Moray Firth; and Blakeney Point in Norfolk, where as a student Salisbury had made a study of the vegetation, which is now a nature reserve. In 2011, Lebas set off in Salisbury’s footsteps. Using both a medium format and a panoramic camera, and with GPS to help her establish the same locations, she focused, as he had, on three subject areas: habitat, locality and specimens. Through working on this project Lebas has learnt to identify species and types of plants and became immersed in a world of classification.

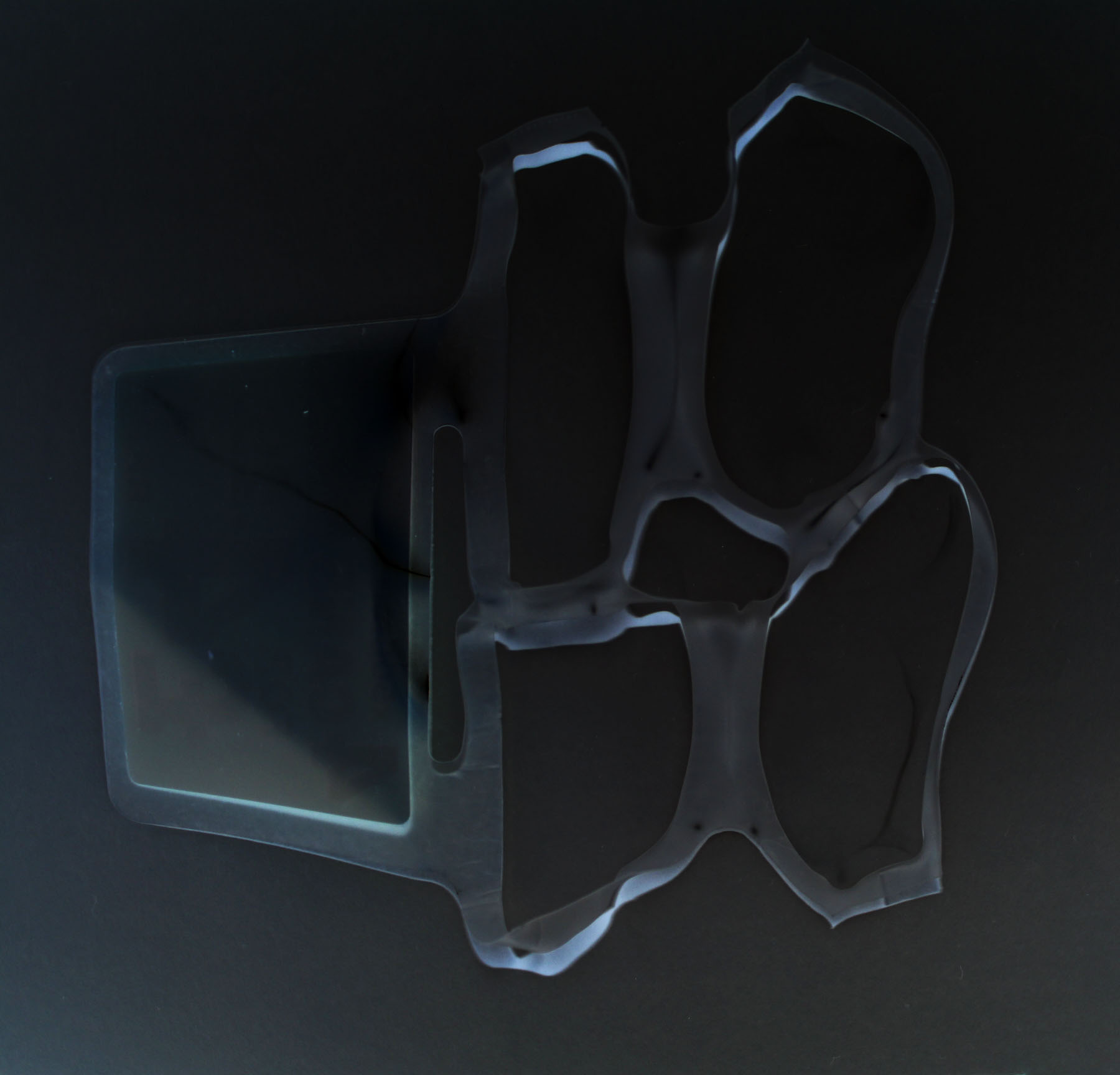

The images appear flat where the silhouette of dead birds float above a dark surface. These mummified birds were found in Houghton Hall’s attic (Norfolk). Fallen from chimneys, the birds had died there due to being trapped. In the above image, the bones of a Long Heared owl can be seen.

The images show a negative colouring due to the process of using photographic paper where the pure white areas show solid parts of the birds body.

Lebas prefers to work at night, or at twilight when the world becomes more mysterious. “I was fascinated by night itself, by the absence of light and the impossibility of photographing”. “I was interested in challenging how I used the cameras, but also challenging the landscape.” Although not presenting a night landscape, this project uses a colour scheme that still reflects the mysterious feel shown in Chrystel Lebas’ other projects.

Overall, the series questions our relationship to the animal’s death and death in nature as a whole.

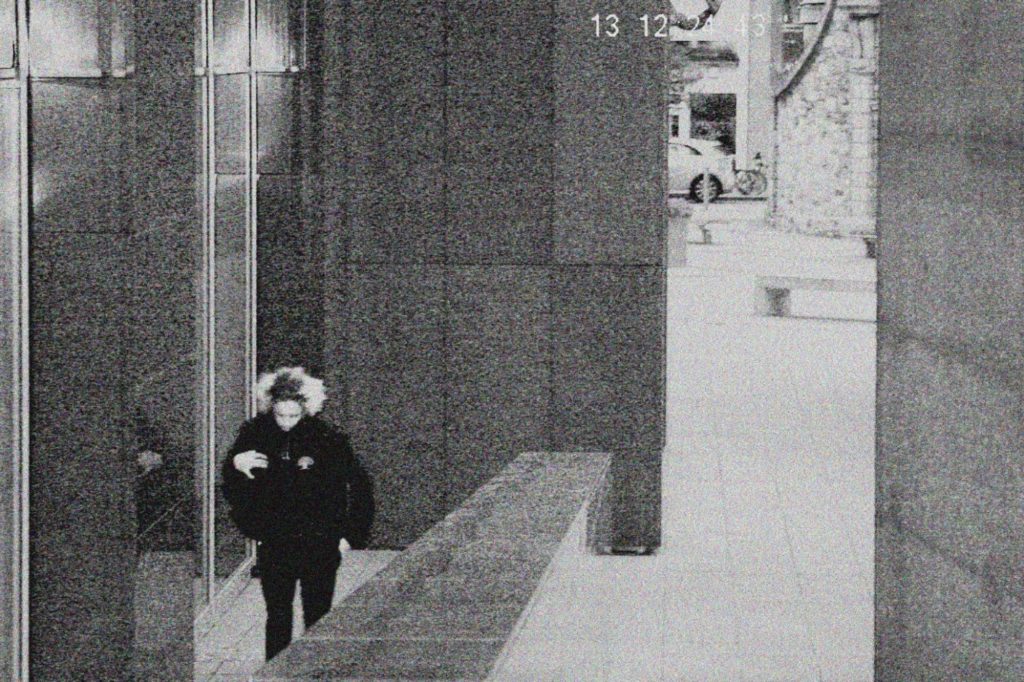

This is one of my favourite images as it is minimalistic yet powerful due to the strong presence of colour in the centre of the image. This occurred due to the use of flash when taking my images. The white paper had turned black after inverting the image. The toothbrush represents a lifestyle of disposable items, used a few times before being thrown away, in some cases not being recycled and ending up in the environment.

This is one of my favourite images as it is minimalistic yet powerful due to the strong presence of colour in the centre of the image. This occurred due to the use of flash when taking my images. The white paper had turned black after inverting the image. The toothbrush represents a lifestyle of disposable items, used a few times before being thrown away, in some cases not being recycled and ending up in the environment.

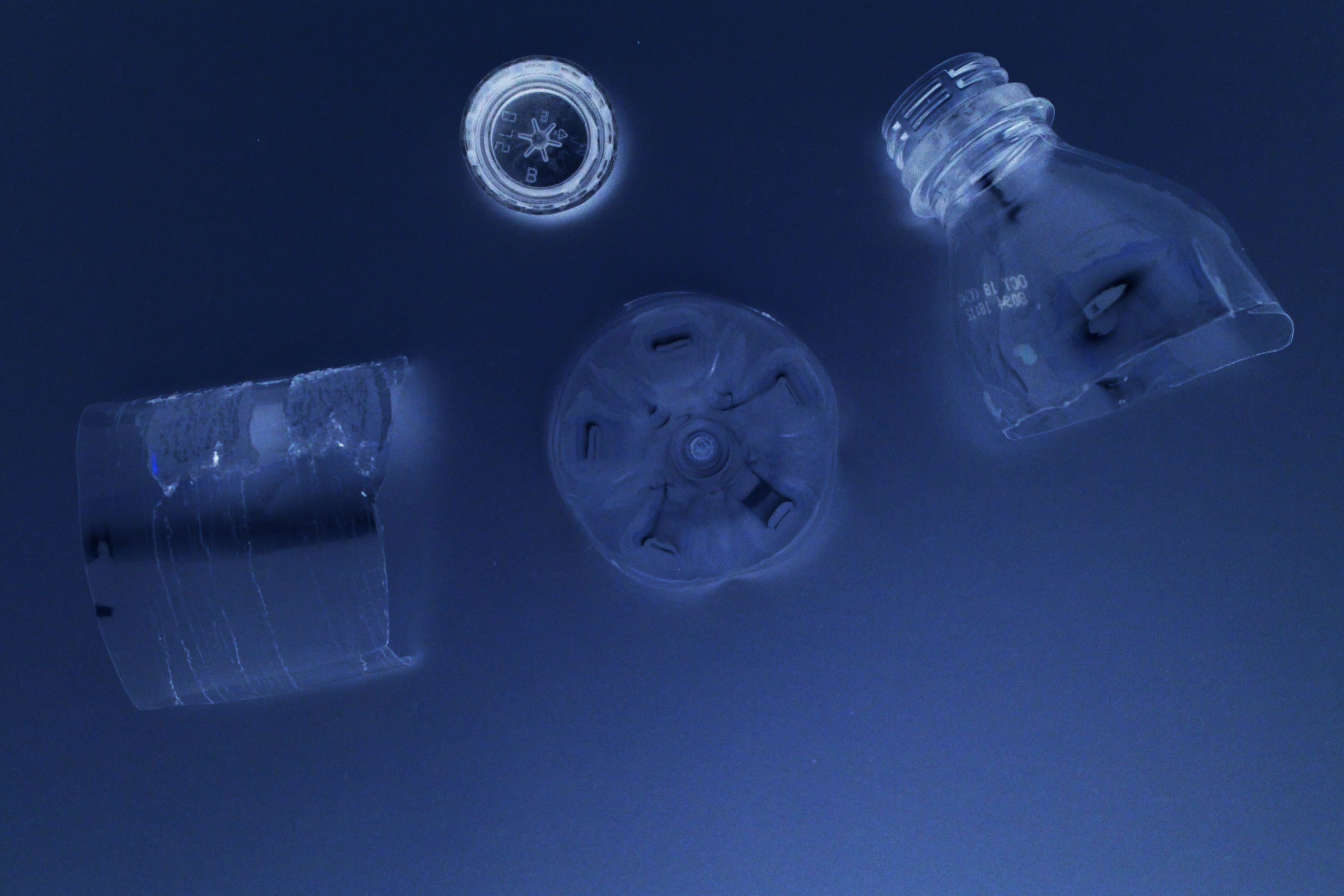

The negative space in these images gives an ocean-like effect, ironically being filled with plastic items.

The negative space in these images gives an ocean-like effect, ironically being filled with plastic items.