Within this essay I will be examining the ways in which both photographers, Lewis Bush and Clare Rae’s work contrast and compliment each other regarding political aspects of Jersey’s development and history. Described as “working to explore forms of contemporary power”, Bush’s stance is to identify the impact of destructive influences over property speculation and redevelopment, picturing the financial scene in Jersey and those involved almost topographically (same composition in different locations). Rae’s work however looks at “questioning issues of representation and the condition of female subjectivity” within domestic and institutional architectures, this is mainly portrayed through the female figure (her own) placed in varying locations, enacting her travels from a larger island of Australia to a smaller island, Jersey. Here I will be exploring how both exhibitions I have visited,Lewis Bush’s Trading Zones and Clare Rae’s Entre Nous and how through their differentiating styles depict their perspective and insight into the path of Jersey’s progression. Considered political to many, Bush’s work revolves around the concept of producing imagery through different photographic approaches such as topography and landscapes. One aspect I found most dominant in his work from the Trading Zone exhibition was his take on how political landscapes of specific businesses shaped its people in accordance with its development. Described as “the self-image of how finance represents itself”Bush gathered images of finance employees and generated an overall figure, done by overlapping various workers profile pictures it created a generalized portrayal of the faces behind the running of businesses, whilst providing us with an insight into the otherwise invisible side of companies. This technique, known as composite pictures, was the off-product of the anthropologist Francis Galton who usedrepeated limited exposure to produce a single blended image of the chronically sick during that time period. However the further into the exhibition I looked the more political the message seemed, an example of this was the board installed filled with various people’s opinions on the financial sector of Jersey. Here by gathering opinions together to form an overall insight into societies perspective of finance it produced an un-bias result, this was because the cards originated from a huge variety of sources such as: schools, finance and retail sectors, and so allowed for feedback into how they viewed Jersey should head towards. Once again inspired by another photographer, called EJ Major, Bush sent out cards of his own in response to hers which had the written question “Love is…” on them, a direct influence for Bush whose own cards had written “Finance is…” on the front of them to engage the audience. In addition to this photographer Clare Rae, whose work I studied in the recent Entre Nous exhibition, looked towards the female figure and the landscape around her as a form of putting across her political views of Jersey. Her form of photography described as “regaining subjectivity and controlling representation” can be linked to how the female figure was criticized regarding gender essentialism, and so the idea of a hidden female face in each image was meant to reflect this specific ideology rather than deflect it. This can be seen as directly confronting the political aspect of her surrounding environment, where her body takes up the form and representation of her “precarious relation to these environments and their narrativity“, compelling the idea of how the subjects gaze upon the image could be interpreted and the idea that could be associated to it. Causing topic for debate regarding “subject of the gaze and the

object of it” from how her uncertainty over issues considering photographic significance and the political stance surrounding it, caused her to turn the camera upon herself and become the subject of the shoot, due to it being her standing point upon the matter. Much of Rae’s working seems to be the focus of the male gaze and the idea of subverting it through the use of female nature (seen here as passive) and male nature (seen here as dominant), challenging this perspective by how she wishes to present the female nature as closer to the environment surrounding them, but instead has been ‘dismantled’ by society as it’s progressed through the ages due to post-structuralist scrutiny. However when contrasting works of both Bush and Rae it can be argued that their political stances are completely different to each others arguing voices. This is due to how I believe that Rae chooses to create her focal point around one particular topic, subversion of the female figure, therefore constricting her opinion to only one or two political perspectives as you can either agree or disagree. Bush on the other hand chooses the wider perspective regarding the entirety of Jersey’s society, instead looking at how the congregated opinions of citizens could come together to form an overall input into the development of Jersey as a whole. Both these standing points clash and compliment each other from how yes, both restrict and broaden their political opinion base completely, but how both look at attempting to sway the perspective and judgment of the viewers towards not what they believe but rather what each individual thinks when they view the work. Each photographer indicates the ever-developing change that has progressed in Jersey’s society, with certain beliefs and viewpoints changing as Jersey did, with some standing put against this advancement rather than join it In conclusion it’s I believe that both photographer’s work can be classed as political through the implicit and explicit messages that most of their photos hold. Though both focus their works on different sectors of Jersey’s history, looking at individuals or entire areas, both conclude the needed or controversial change that has occurred and the distinct voices that many embrace regarding the future of not just St. Helier but the whole of Jersey and the path being headed towards. This as a result becomes a hugely political debate as both photographers do not look just at their opinions but rather those who they see as being effected by the change that should or has occurred.

Daily Archives: September 13, 2018

Filters

Exploring And Planning Manifestos

What is a manifesto?

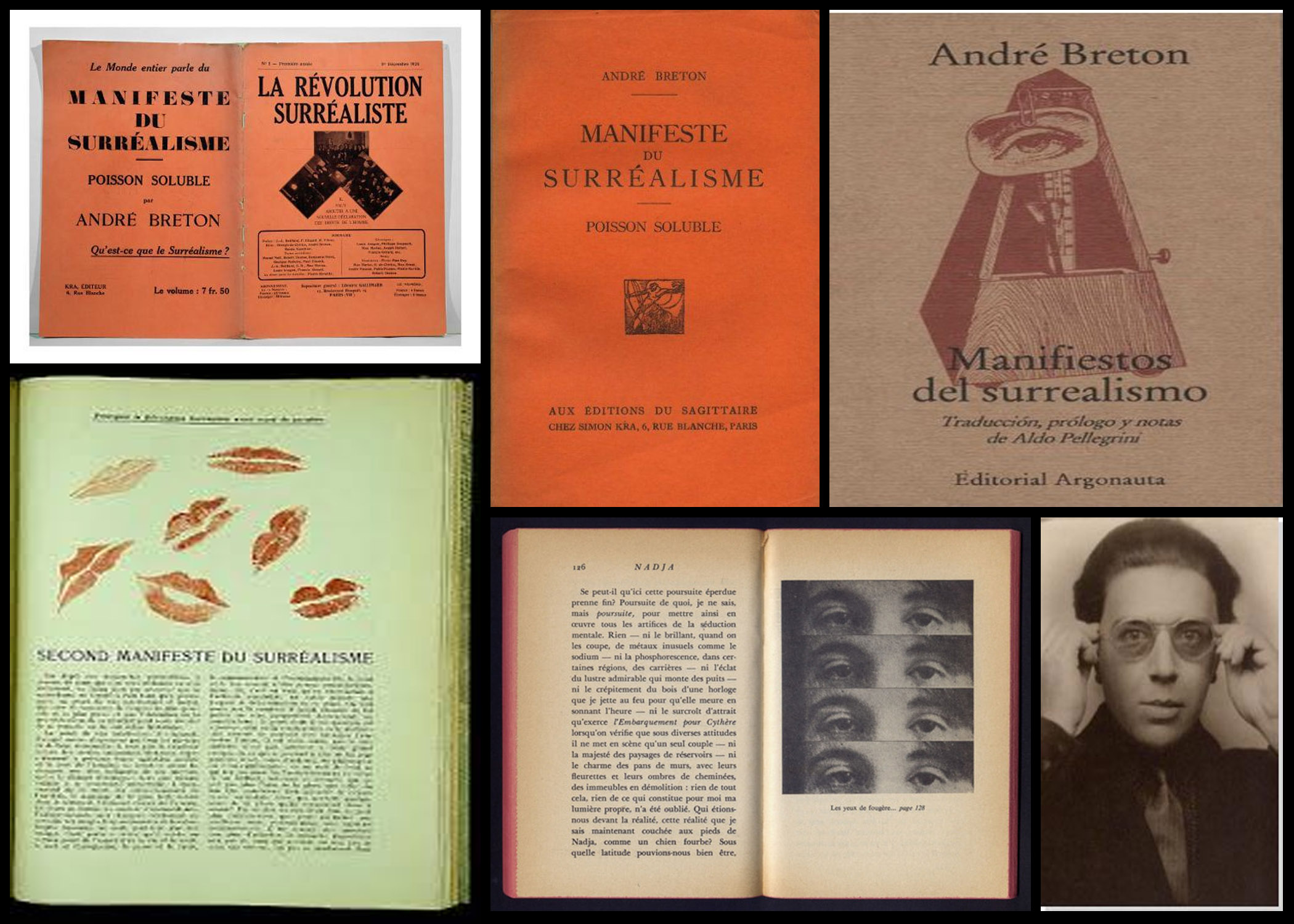

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a new idea with prescriptive notions for carrying out changes the author believes should be made. It often is political or artistic in nature, but may present an individual’s life stance. Manifestos relating to religious beliefs are generally referred to as creeds. I will be looking at a chosen manifesto, identifying what it is an what it argues. The manifesto I have selected is called Andre Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto.

The main goal of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism is to free one’s mind from the past and from everyday reality to arrive at truths one has never known. By the time Breton wrote his manifesto, French poets—including Breton himself—and artists had already demonstrated Surrealist techniques in their work. In this sense, Breton was intent on explaining what painters and poets such as Giorgio de Chirico, Joan Miró, Robert Desnos, Max Ernst, and Breton himself had already achieved.

In Breton’s view, one can learn to ascend to perception of a higher reality (the surreal), or more reality, if one can manage to liberate one’s psyche from traditional education, the drudgery of work, and the dullness of what is only useful in modern bourgeois culture. To achieve the heightened consciousness to which Breton wants humanity to aspire, those interested can also look to the example set by children, poets, and to a lesser extent, insane persons.

Children, Breton suggests, have not yet learned to stifle their imaginations as most adults have, and successful poets have, similarly, been able to break down the barriers of reason and tradition and have achieved ways of seeing, understanding, and creating that resemble the free, spontaneous imaginative play of children. On the other hand, as one grows up, one’s imagination is dulled by the need to make a living and by concern for practical matters. Hence, in the manifesto’s opening paragraphs, Breton calls for a return to the freedom of childhood. Furthermore, if the “insane” are, as Breton suggests, victims of their imaginations, one can learn from the mentally ill that hallucinations and illusions are often sources of considerable pleasure and creativity.

Because of Freud, Breton says, human beings can be imagined as heroic explorers who are able to push their investigations beyond the mere facts of reality and the conscious mind and seize dormant strengths buried in the subconscious. Freud’s work on the significance of dreams, Breton says, has been particularly crucial in this regard, and the manifesto contains a four-part defense of dreams.

Planning a response When creating my own manifesto regarding political landscape I intend to use consumerism as the basis for my work. However I would like to possibly incorporate surrealism into my work along the way, using enhancement to create dream like landscapes which don’t really reflect the true nature of that area. To do this I would be using software such as Photoshop and Lightroom to create the products desired, as they provide me with the necessary tools required. I want my manifesto to be creative, looking at varying sides of consumerism not just one aspect, allowing for diversity in my work produced. I would love to use colour and vibrancy as one of my leading aspects in the manifesto as it would provide the audience with aesthetic and appealing imagery that had a deeper meaning under the surreal appearance.

When creating my own manifesto regarding political landscape I intend to use consumerism as the basis for my work. However I would like to possibly incorporate surrealism into my work along the way, using enhancement to create dream like landscapes which don’t really reflect the true nature of that area. To do this I would be using software such as Photoshop and Lightroom to create the products desired, as they provide me with the necessary tools required. I want my manifesto to be creative, looking at varying sides of consumerism not just one aspect, allowing for diversity in my work produced. I would love to use colour and vibrancy as one of my leading aspects in the manifesto as it would provide the audience with aesthetic and appealing imagery that had a deeper meaning under the surreal appearance.