Walker Evans (born November 3, 1903) was an American photographer and photojournalist whose influence on the evolution of ambitious photography during the second half of the 20th century was perhaps greater than that of any other figure. Evans had the extraordinary ability to see the present as if it were already the past, and to translate that knowledge and historically inflected vision into an enduring art

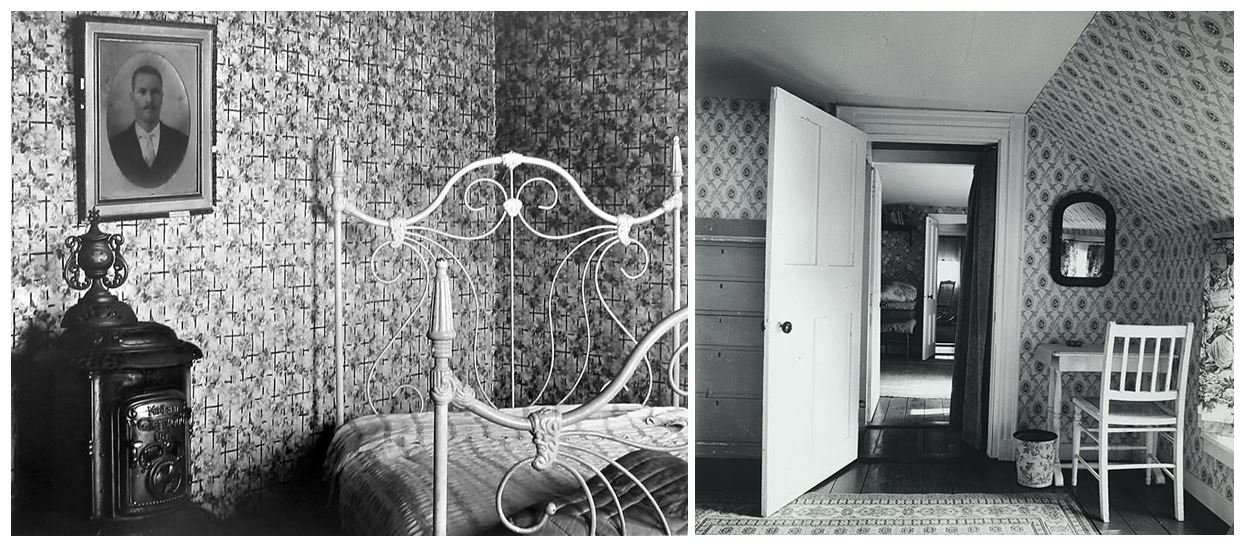

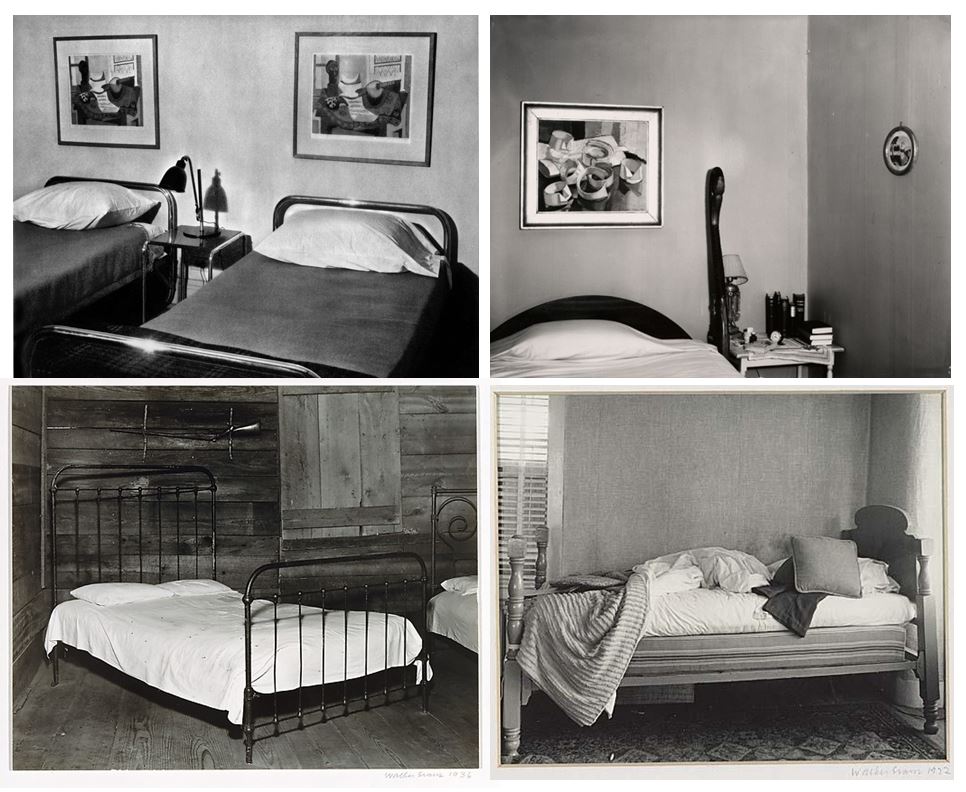

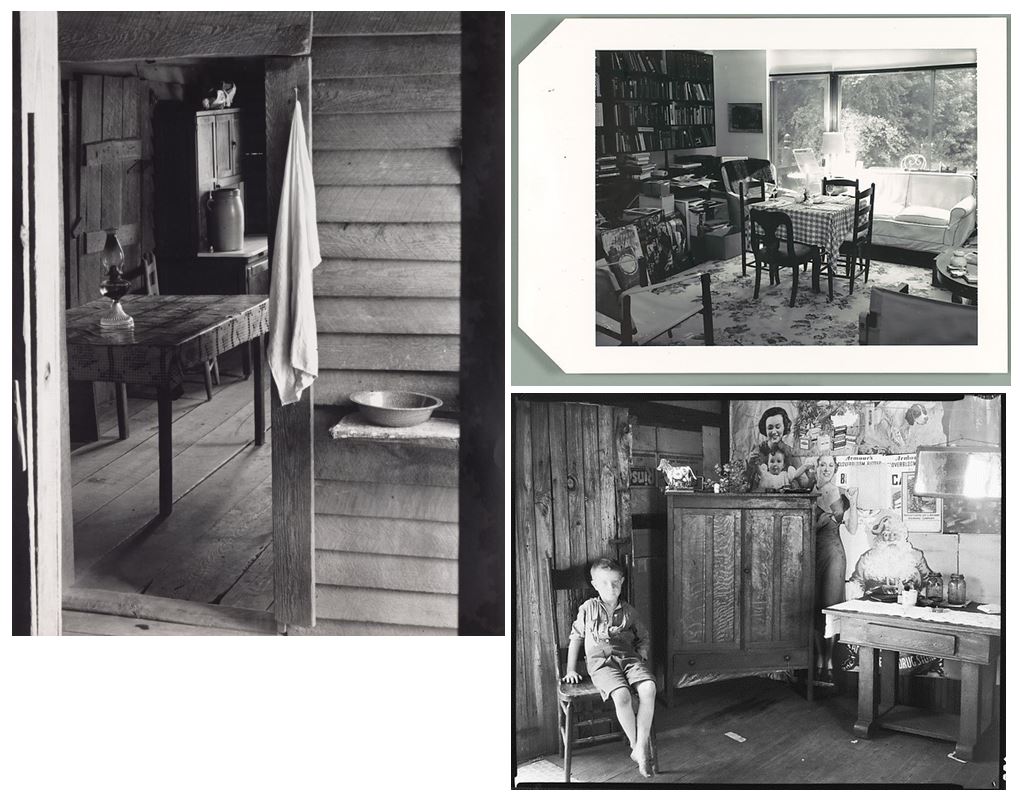

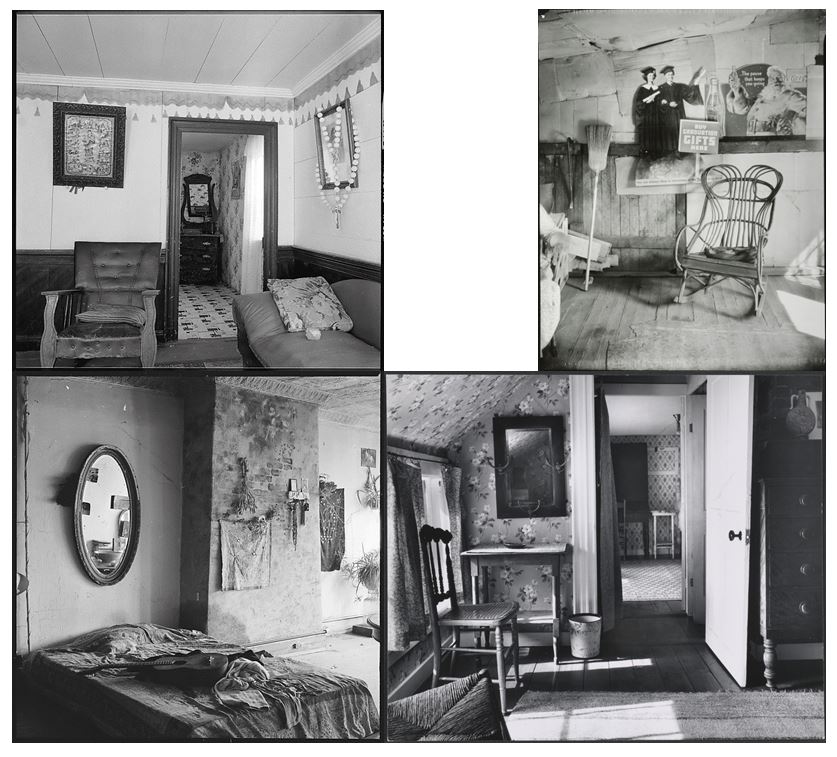

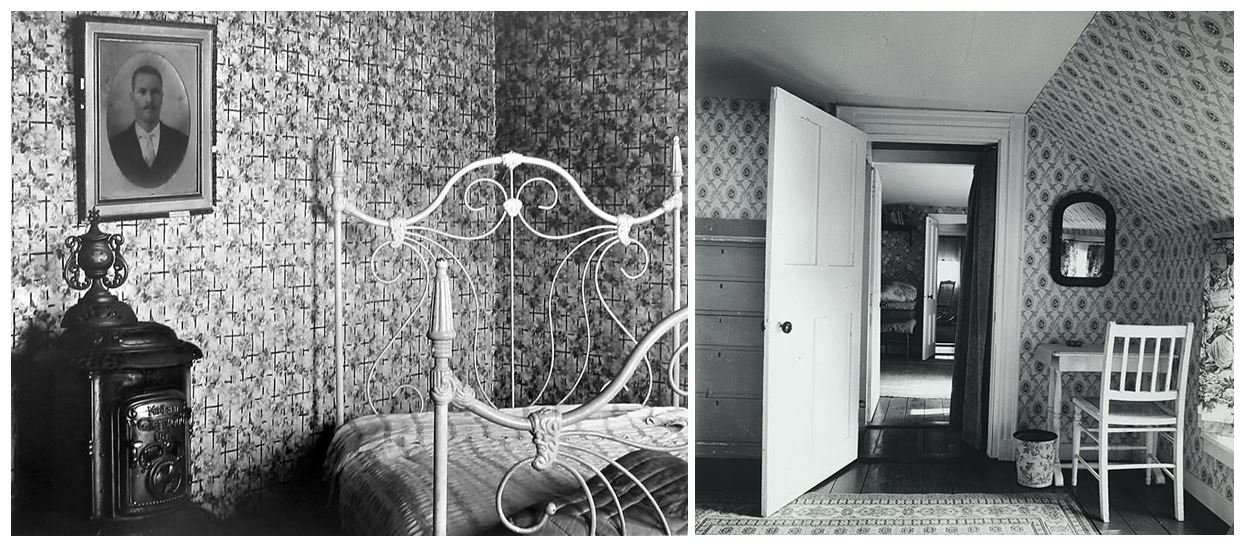

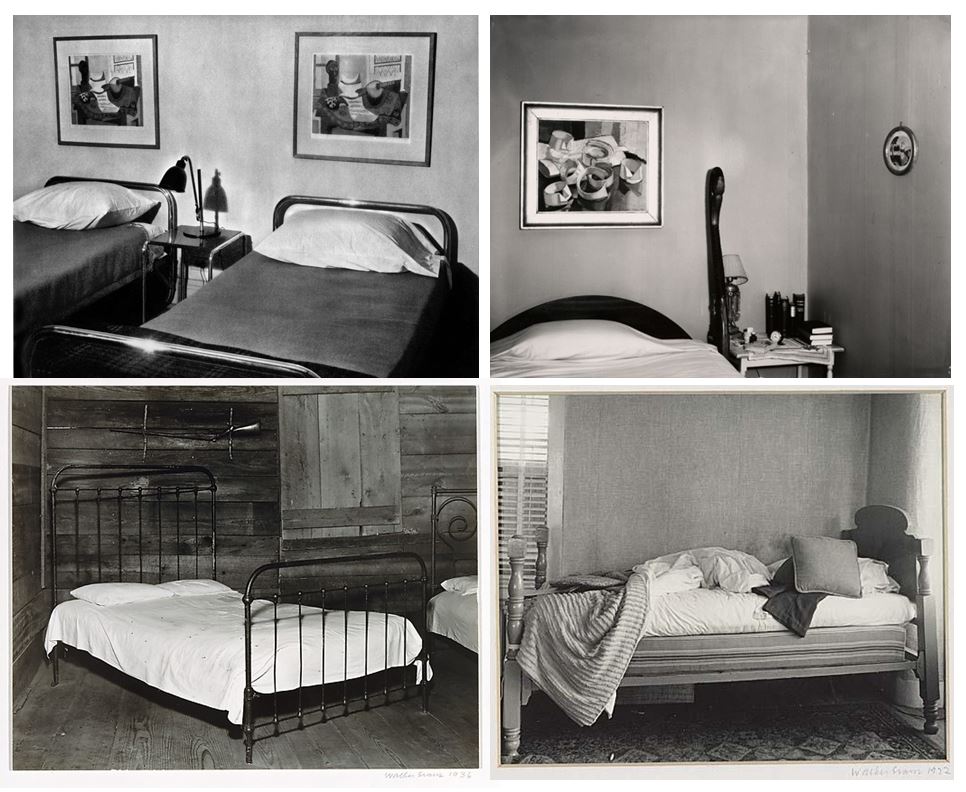

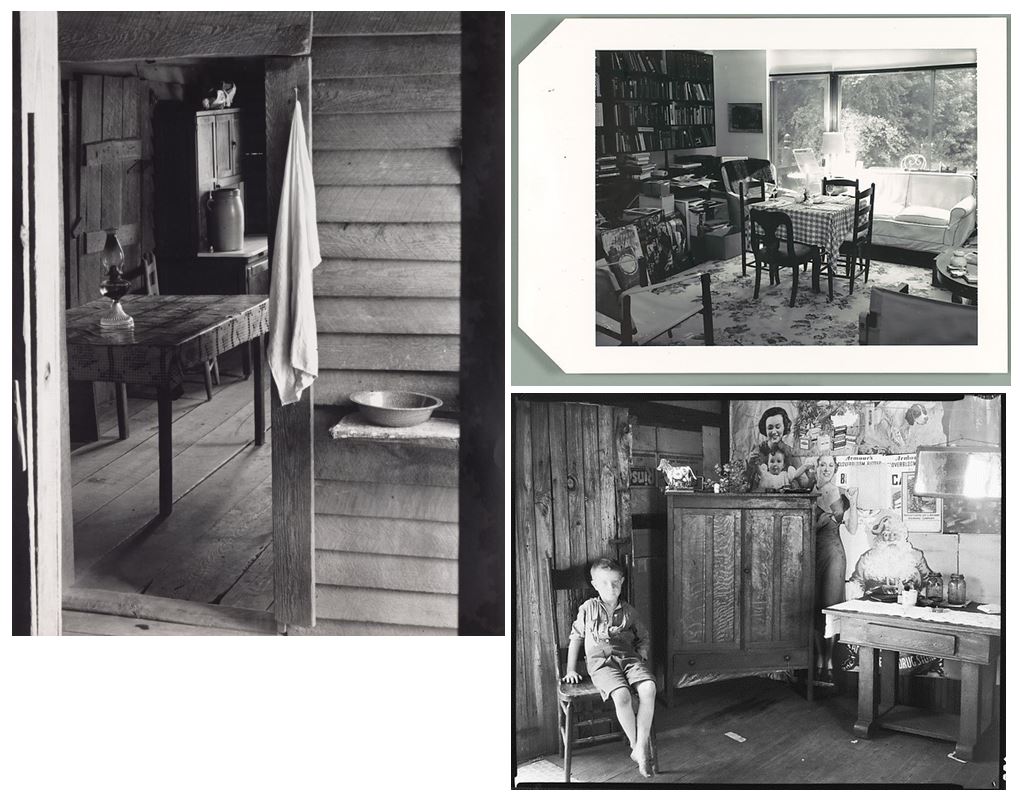

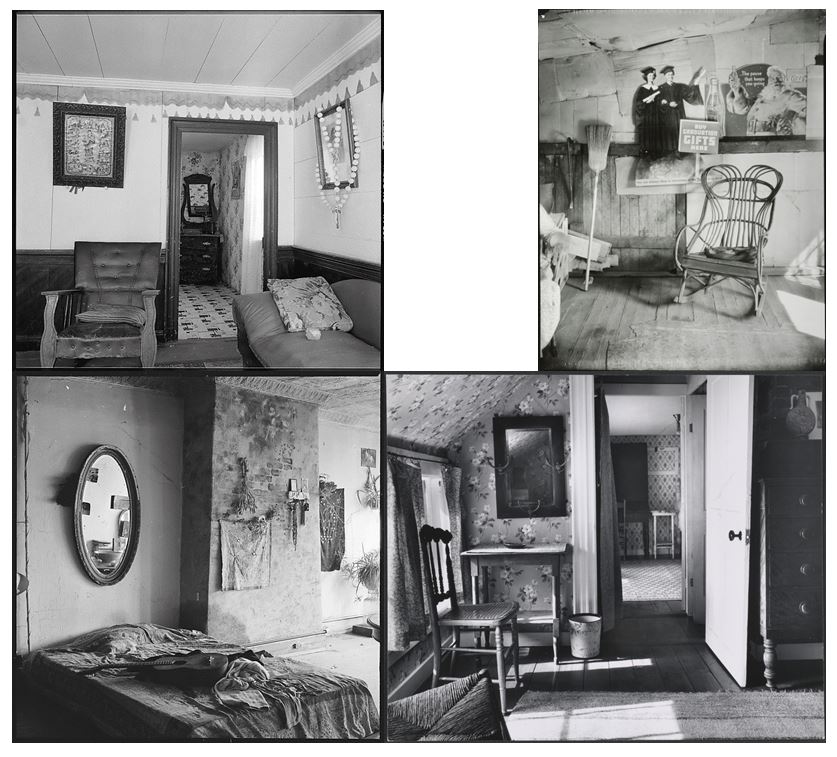

His principal subject was the vernacular—the indigenous expressions of a people found in roadside stands, cheap cafés advertisements, simple bedrooms, and small-town main streets.

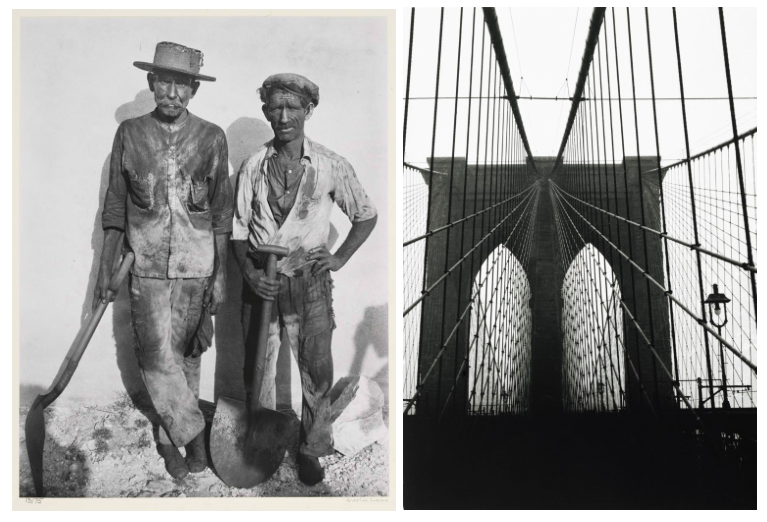

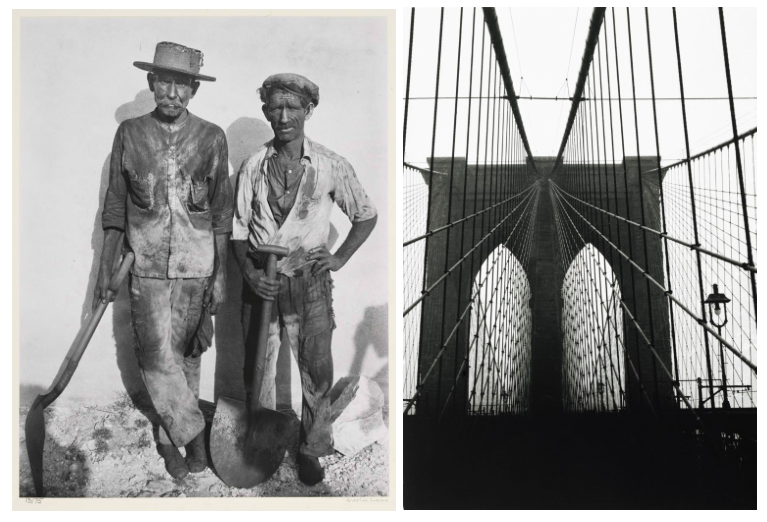

Evans began photographing regularly in 1928, while living in New York City. It was his goal to become a professional photographer, although it was difficult to find work. His first big break came in 1930, when three of his photographs were selected to be published in a poetry book by Hart Crane, titled The Bridge. This early work foreshadows his life-long interest in the imagery of urban architecture and industrial construction.

In 1933, Evans traveled to Cuba to take photographs for The Crime of Cuba, a book by American journalist Carleton Beals. Beals’s goal was to expose the corruption of Cuban dictator Gerardo Machado. For this project, Evans produced a number of portrait photographs using laborers, miners, and dockworkers. He also documented the urban street life in Cuba, including images of vendors, pedestrians, and signage. All of these themes would reappear in Evans’s later work for the FSA.

Mature Period

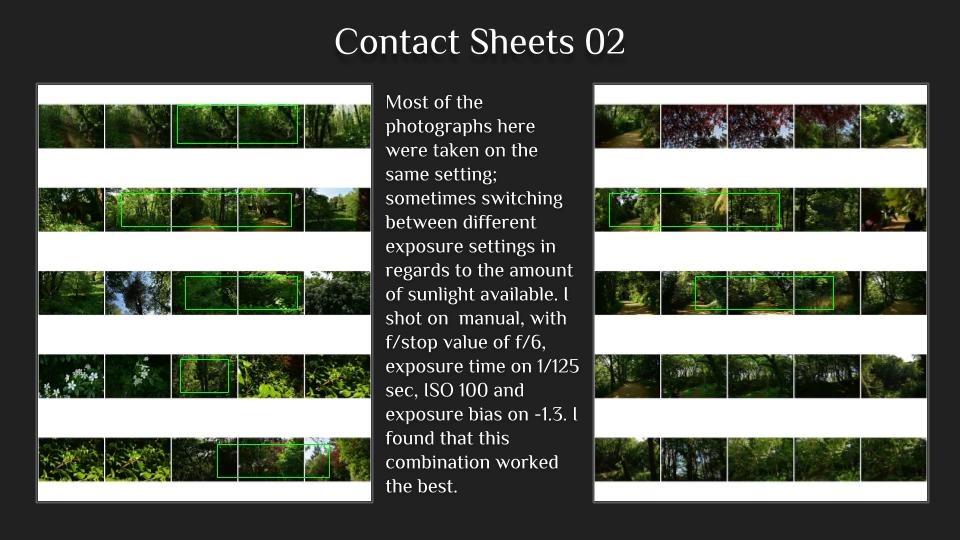

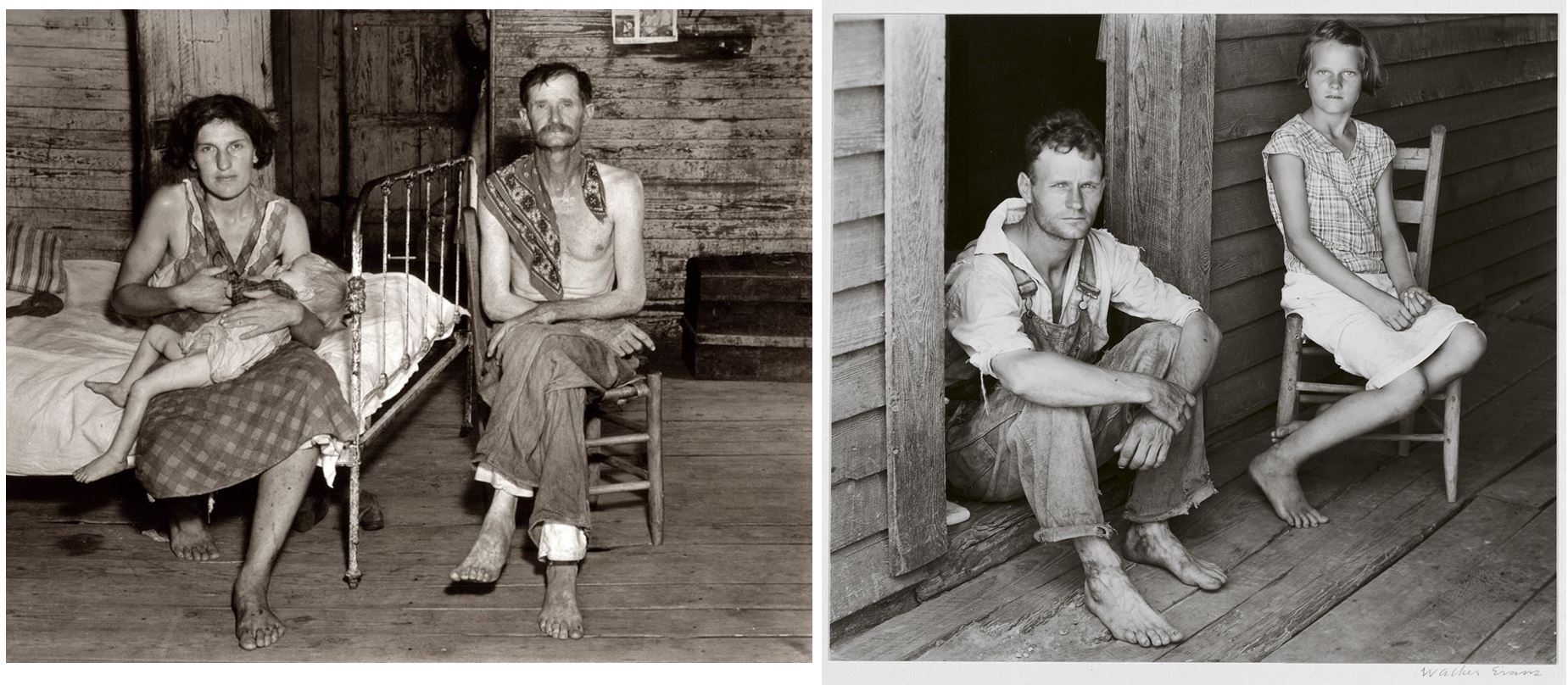

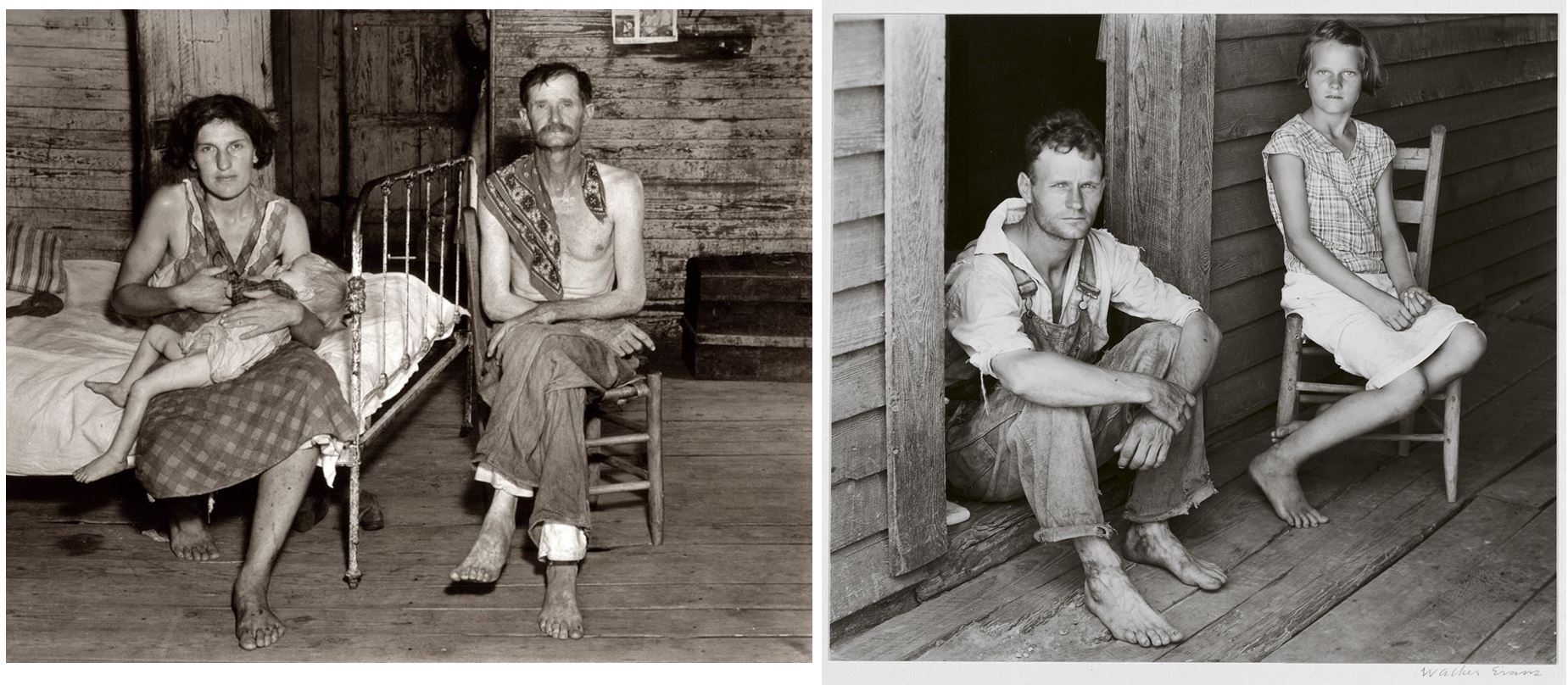

Photography flourished under the Great Depression, thanks to Roosevelt’s New Deal, which paid artists to work. The Farm Security Administration hired Evans alongside other photographers to document the government’s improvement efforts in rural communities. Unconcerned with the political ideology behind his assignment, Evans spent the better part of 1935 and 1936 eloquently capturing the aesthetic texture of ordinary life via rural churches, bedrooms, faded signs, and rumpled work clothes. He avoided using upscale equipment. Despite being familiar with and capable of affording the latest technology, Evans used an outdated camera with a very slow lens.

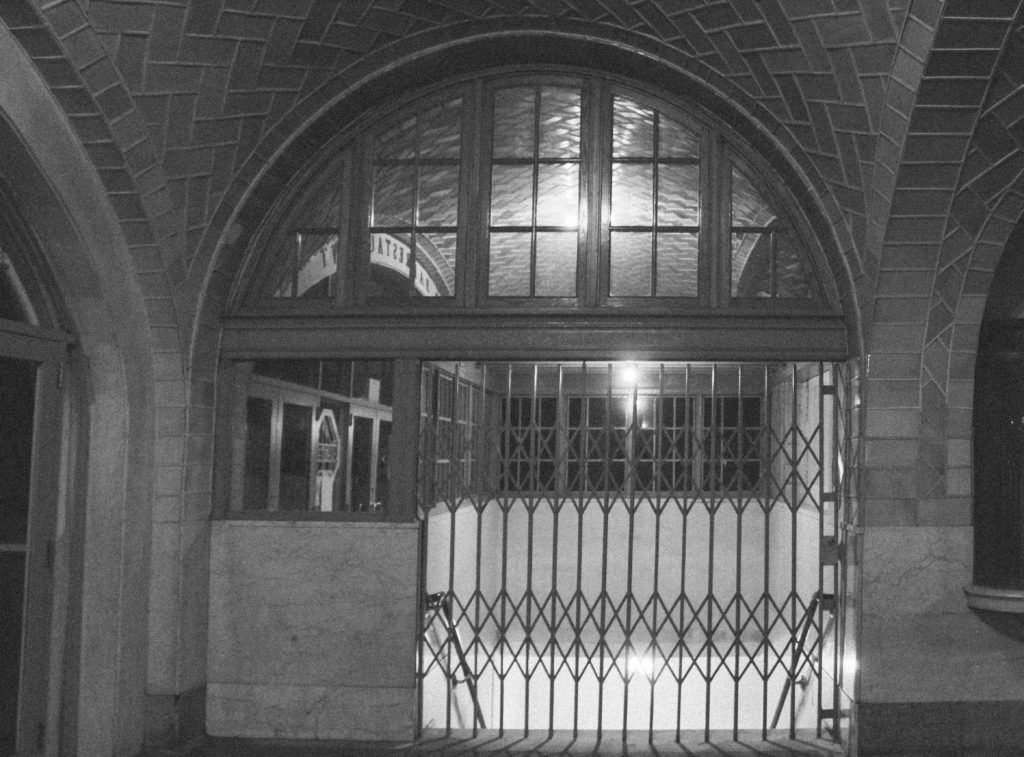

Evans’ interiors function like landscapes that open up towards other worlds, largely through the particular attention that he pays to the inanimate objects that are present, almost representing them as characters themselves

His book titled – Message from the interior – is both open and reserved, preparing the reader not only for its subject matter, but also for the atmosphere of intensity it contains. Here, through objects and places, the he speaks to us of absence, the difficulty of communication and the passage of time.

Walker Evans picks out details that unsettle our delicate balance with portraits set in living rooms, kitchens or bedrooms. On first impression, the meticulous layout of the images leave room for the disciplined and temporarily deserted places that they depict.

None the less there is resistance, in spite of all of these codes and the apparent passivity of these empty, predetermined spaces. Life is indeed present, in the smell of the wallpaper, the sound of the wooden floors, the slight movements of dust particles and the lengthening of shadows.

These spaces, now emptied of their occupants, rediscover their own life, perspectives stretch out or become flattened; shadows recompose themselves into sculptures, as the objects take over the roles of the missing occupants and complete the story.

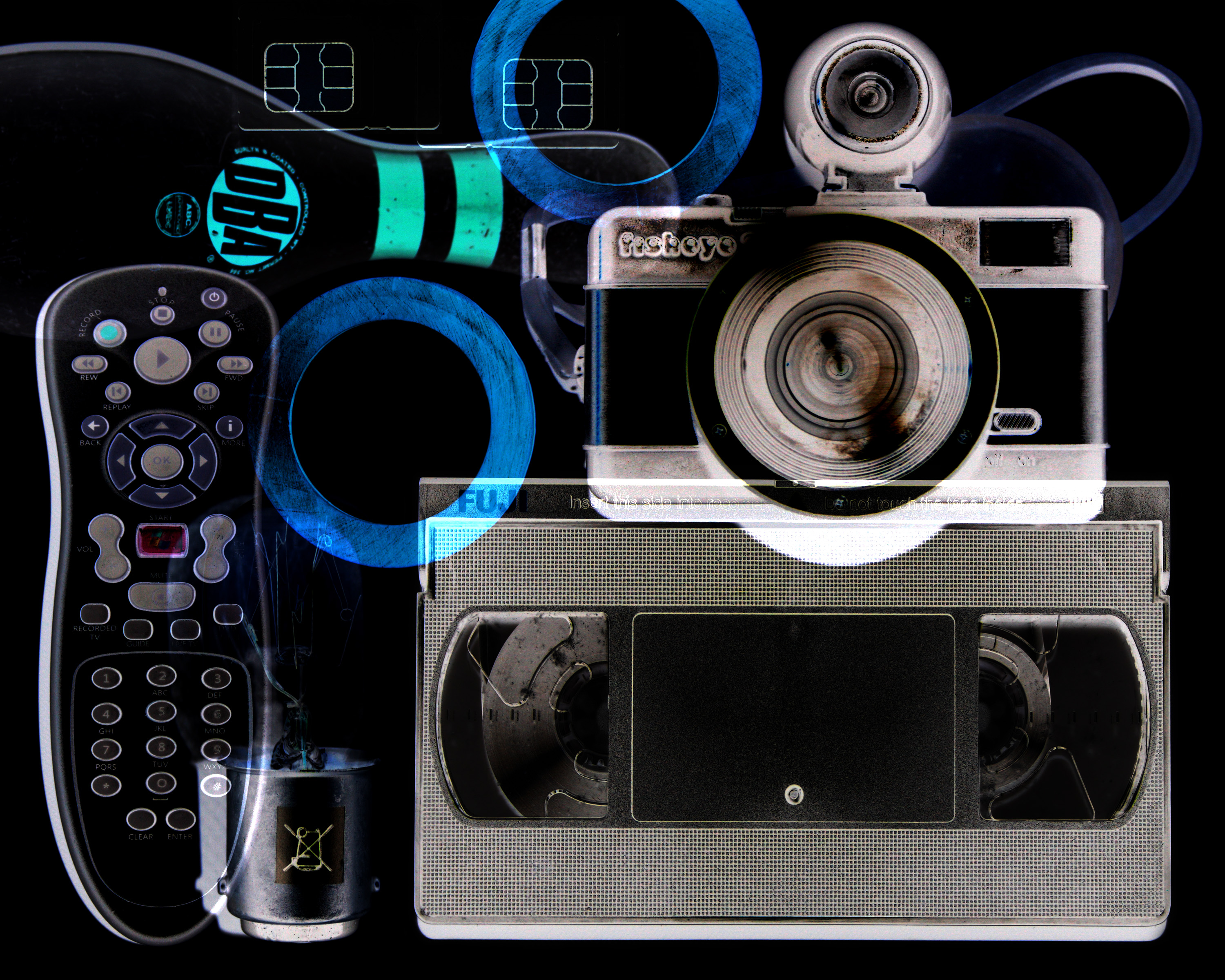

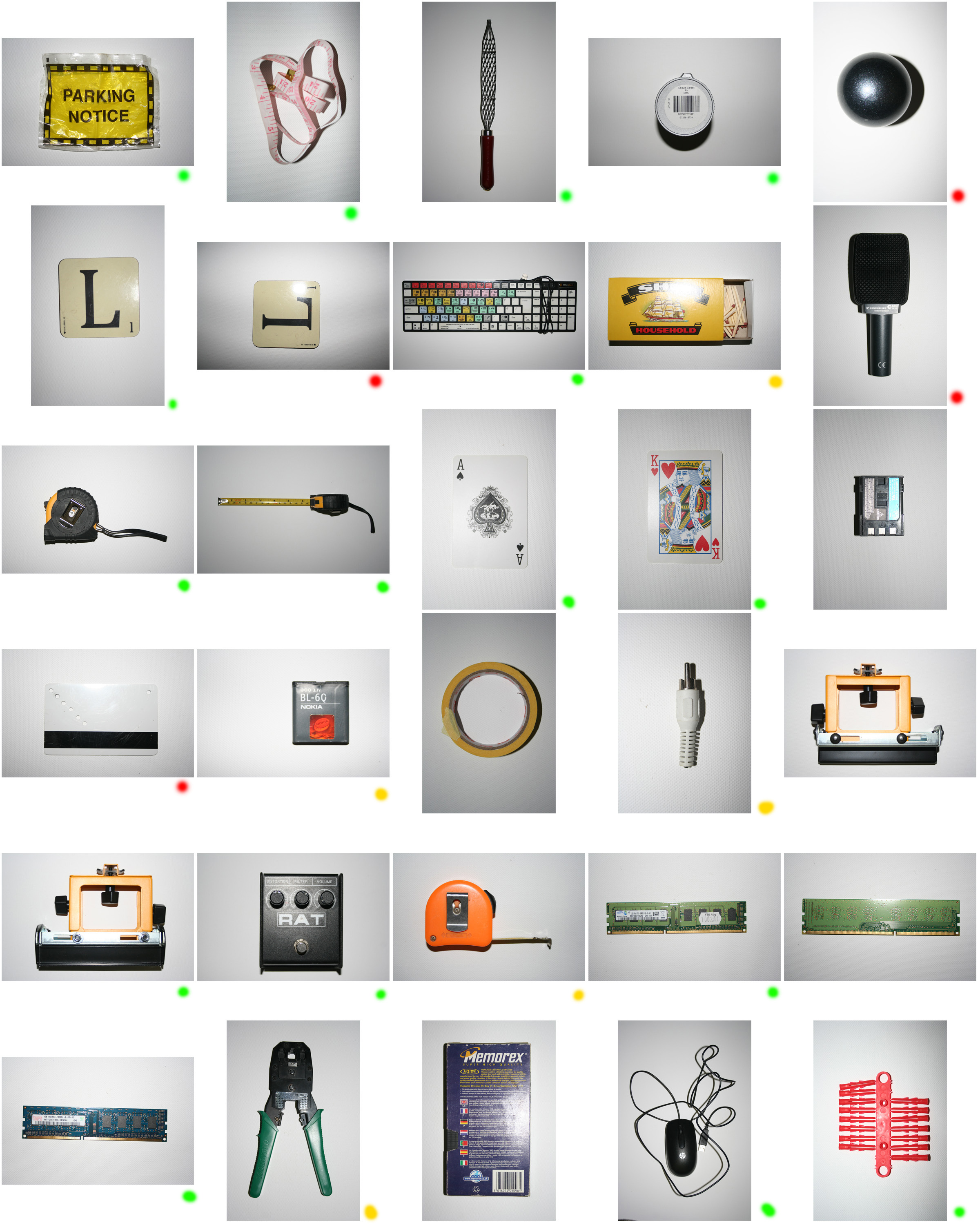

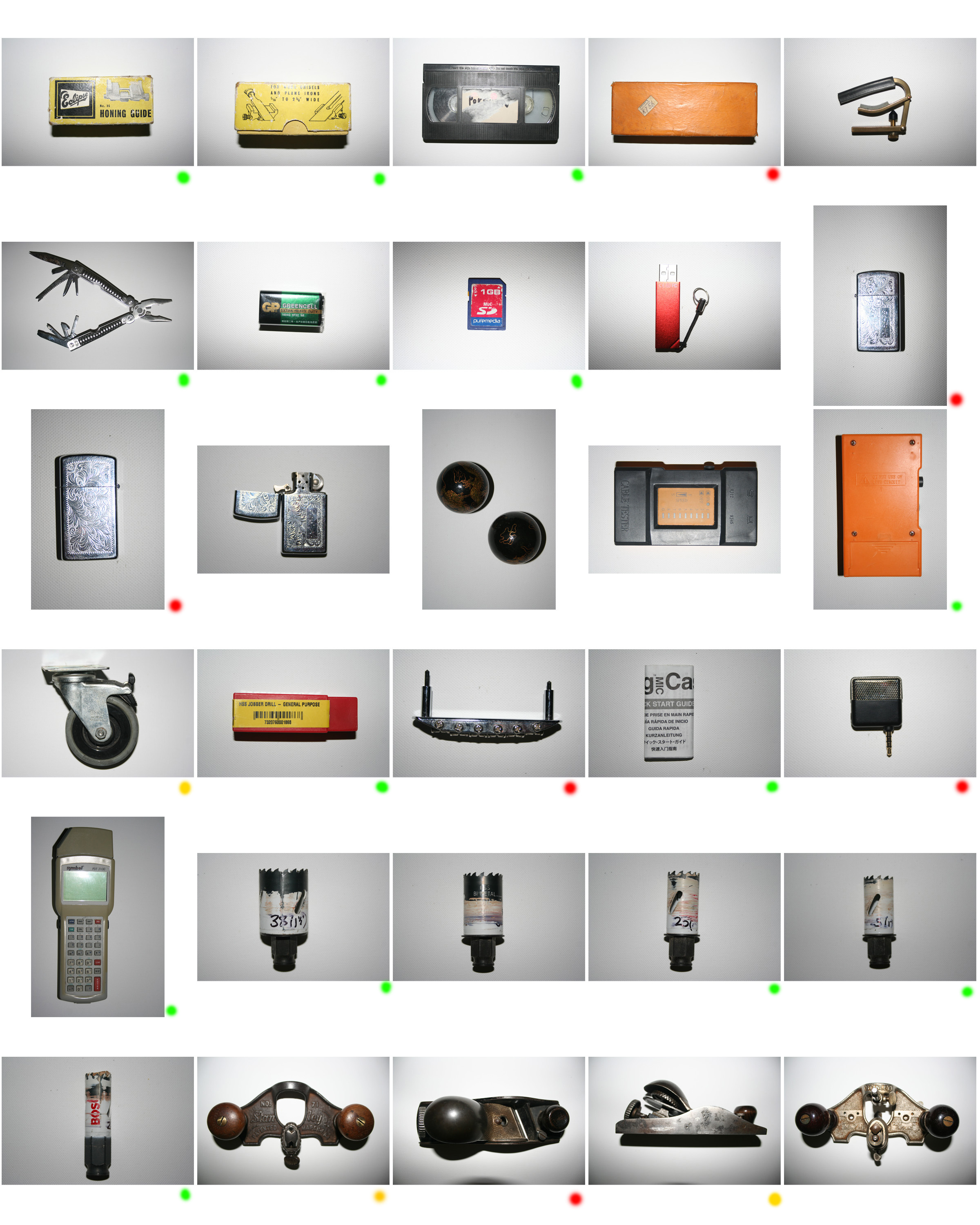

![]() Most of Evans’s best work dealt not with people but with the things they made: he was concerned most of all with the character of American culture as it was expressed in its vernacular architecture and in its unofficial decorative arts, such as billboards and shop windows.

Most of Evans’s best work dealt not with people but with the things they made: he was concerned most of all with the character of American culture as it was expressed in its vernacular architecture and in its unofficial decorative arts, such as billboards and shop windows.

In Evans time, there were essentially two competing philosophies of photography: Documentary vs. Pictorialist. Documentary strove to represent the world as it was, flaws and all; Pictorialism produced a selective, transcendent view of the world, akin to traditional Western painting. Evans’s work, a blend of these two philosophies, brought greater nuance to the practice of photography. As he put it, “What I believe is really good in the so-called documentary approach to photography is the addition of lyricism… produced unconsciously and even unintentionally and accidentally by the cameraman.”

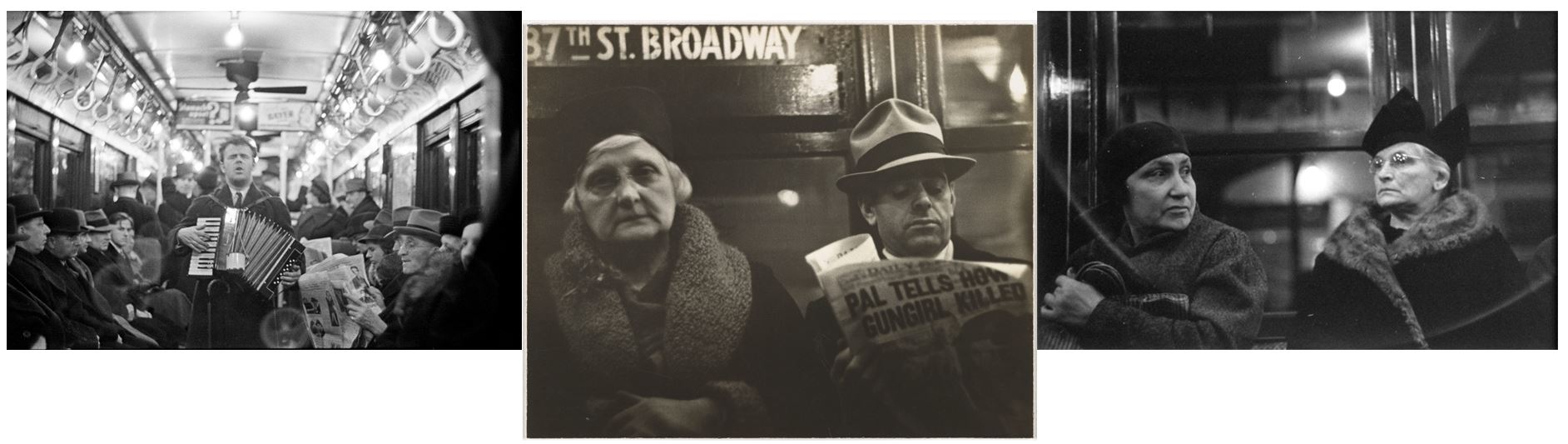

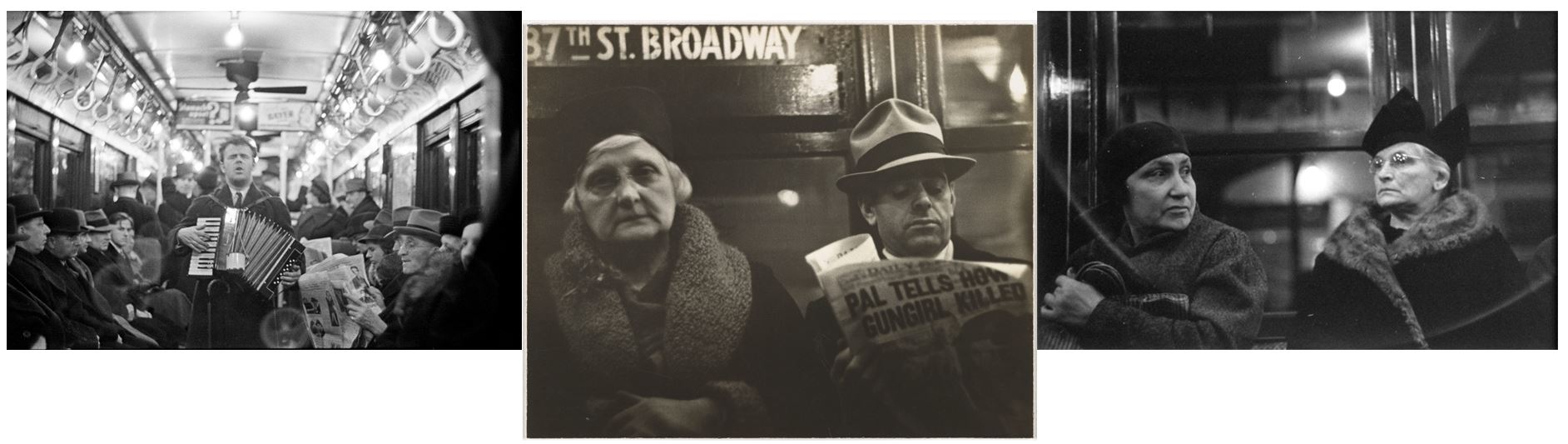

During the winter months between 1938 and 1941, Evans strapped a camera to his midsection, cloaked it with his overcoat, and snaked a cable release down his suit sleeve to photograph New York City subway passengers unawares.

For Evans, the subway portraits were an attempt to capture the ultimate purity of a recording method without human interference. He sought to reflect ordinary life in an organic and natural way. The subway portraits were also, in many ways, a rebellion against studio portraiture and the commercialization of photography. Evans criticized the inherently artificial nature of typical portrait photography, with its use of costumes, make-up, props, and posed stances.

Best Images

Best Images