When photography was invented in 1839, it was a black-and-white medium, and it remained that way for almost one hundred years. Photography then was a fragile, cumbersome, and expensive process. In order to practice, photographers needed a lot of extra money and time, or a sponsor. In that early period, the people advancing photographic technology tended to focus not on achieving color photographs but on making improvements in the optical, chemical, and practical aspects of photography. For many, the goal was to make photography more suitable for portraiture—its most desired application. For that, photographic technology needed to be more stable, portable, and affordable, not more colorful. But people wanted color photos. (Portraits before photography were paintings—in full, glorious color.) By 1880, once the early technical hurdles had been overcome, portrait photographers began experimenting with color. They employed artists to tint photographers’ daguerreotypes and calotypes by hand.

British photographers introduced hand coloring photographs to Japan, where the practice became widespread and Japanese artists further perfected the technique. The refined, delicate hand coloring became a defining characteristic of Japanese tourist photography, the results of which were carried back to the West, influencing the art of hand coloring there. This wildly popular technique persisted in Europe and the Americas until twenty years later when Autochrome plates arrived. In Japan, hand coloring lasted yet another twenty years beyond.

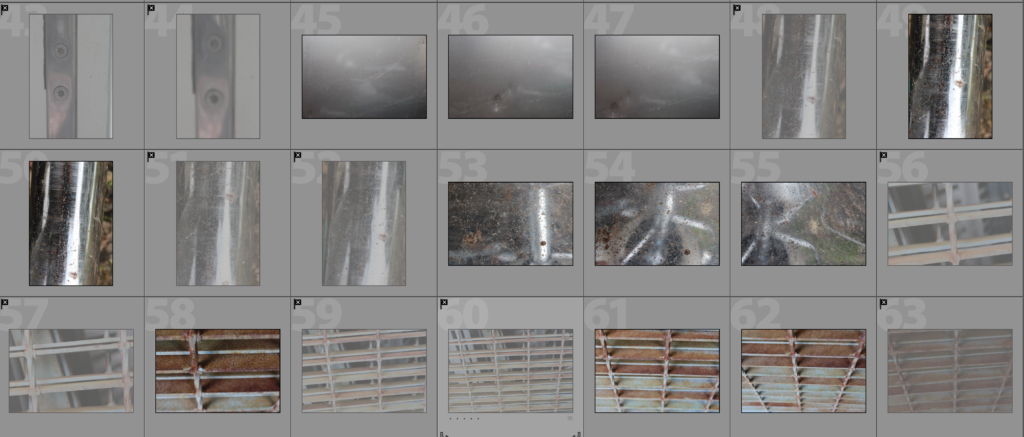

When first attempted in early 1840s people were trying to find a sort of chameleon substance which would be be able to assume the colour of any light falling upon it. The first results were typically obtained from projecting a solar spectrum directly onto the sensitive surface promising an eventual success, however a comparatively dull image would form in the camera required exposures lasting for hours or even days. The quality and range of the image colour were sometimes severely limited mainly due to primary colours, such as the chemically made ‘Hillotype’ process invented by America Levi Hill in 1850. Many others tried to experiment with other methods that prevented colours from fading over time such as Edmond Becquerel who achieved better results to some extent. Over about seven decades there was continuous experiments along these lines which would occasionally raise hopes but having no value at practical level. Here are some examples of early coloured photography:

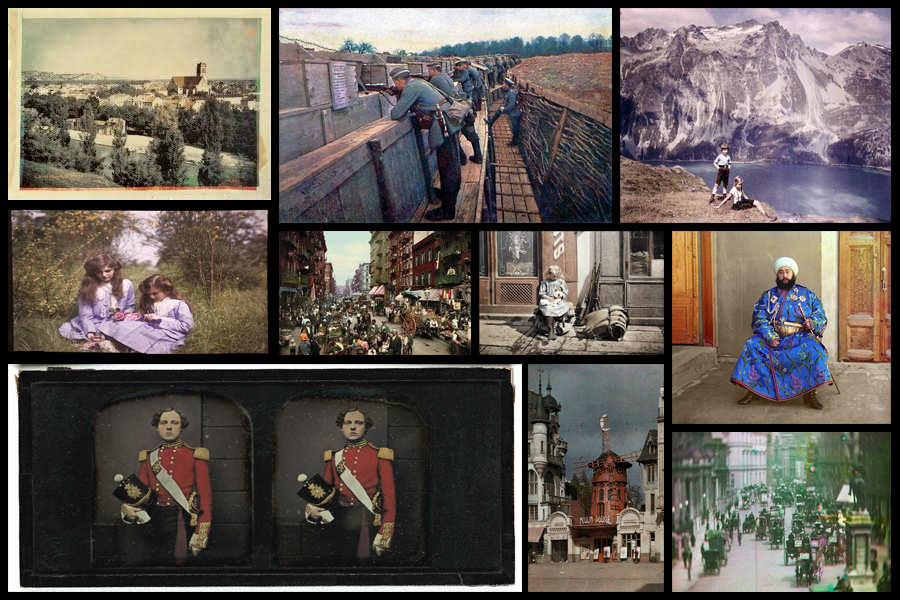

Regarding the first ever colour photograph it was taken as early as 1826 by Nicephore Niepce, however it took until 1861 to be developed by technology which could incorporate very basic colour. Overall though it was the Scottish Physicist and poet James Clerk Maxwell who produced the first true colour photograph that didn’t fade immediately or need colour adding afterwards by hand. The image can be interpreted as sinister and mysterious, this is because the colours red, green and blue have been used to take a still image of some tartan ribbon which had to be taken three times using different coloured filters each time. The technique itself was developed because of the theories about how the eye can process colour. This is the first non-fading coloured image:

The three-colour method, which is the foundation of virtually all practical color processes whether chemical or electronic, was first suggested in an 1855 paper on colour vision by Maxwell. It is based on the Young-Helmholtz theory that the normal human eye perceives colour because the retina is covered with millions of intermingled cone cells of three different types: In theory, one type is most sensitive to the end of the spectrum we call “red”, another is more sensitive to the middle or “green” region, and a third which is most strongly stimulated by “blue”. The named colours are somewhat arbitrary divisions imposed on the continuous spectrum of visible light, and the theory is not an entirely accurate description of cone sensitivity. Nevertheless, it coincides enough with the sensations experienced by the eye that when these three colors are used the three cones types are adequately and unequally stimulated.

In his studies of color vision, Maxwell showed, by using a rotating disk with which he could alter the proportions, that any visible hue or gray tone could be created by mixing only three pure colours of light red, green and blue in proportions that would stimulate the three types of cells to the same degrees under particular lighting conditions. To emphasize that each type of cell by itself did not actually see colour but was simply more or less stimulated, he drew an analogy to black-and-white photography: if three colorless photographs of the same scene were taken through red, green and blue filters, and transparencies made from them were projected through the same filters and superimposed on a screen, the result would be an image reproducing not only red, green and blue, but all of the colors in the original scene. Because Sutton’s photographic plates were in fact insensitive to red and barely sensitive to green, the results of this pioneering experiment were far from perfect.