The Rorschach test is a psychological test in which subjects’ perceptions of inkblots are recorded and then analysed using psychological interpretation, complex algorithms, or both. Some psychologists use this test to examine a person’s personality characteristics and emotional functioning. It has been employed to detect underlying thought disorder, especially in cases where patients are reluctant to describe their thinking processes openly. The test is named after its creator, Swiss psychologist Hermann Rorschach. In the 1960s, the Rorschach was the most widely used projective test.

Using interpretation of “ambiguous designs” to assess an individual’s personality is an idea that goes back to Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. Interpretation of inkblots was central to a game, Gobolinks, from the late 19th century. Rorschach’s, however, was the first systematic approach of this kind. The ink blots were hand drawn by Rorschach.[

It has been suggested that Rorschach’s use of inkblots may have been inspired by German doctor Justinus Kerner who, in 1857, had published a popular book of poems, each of which was inspired by an accidental inkblot. Kerner pioneered Klecksography, the art of making images from inkblots. French psychologist Alfred Binet had also experimented with inkblots as a creativity test, and, after the turn of the century, psychological experiments where inkblots were utilized multiplied, with aims such as studying imagination and consciousness.

After studying 300 mental patients and 100 control subjects, in 1921 Rorschach wrote his book Psychodiagnostik, which was to form the basis of the inkblot test (after experimenting with several hundred inkblots, he selected a set of ten for their diagnostic value).

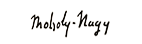

Inkblot 1

Inkblot 2

Inkblot 3

Inkblot 4

Inkblot 5

Inkblot 6

Popular Responses as according to various authors:

Inkblot 1: Beck: two humans (grey), Piotrowski: human figures (72%, grey), Dana (France): human (76%, grey)

Inkblot 2: Beck: bat, butterfly, moth, Piotrowski: bat (53%), butterfly (29%), Dana (France): butterfly (39%)

Inkblot 3: Beck: two humans, Piotrowski: four-legged animal (34%, grey parts), Dana (France): animal: dog, elephant, bear (50%, grey)

Inkblot 4: Beck: animal hide, skin, rug, Piotrowski: animal skin, skin rug (41%), Dana (France): animal skin (46%)

Inkblot 5: Beck: bat, butterfly, moth, Piotrowski: butterfly (48%), bat (40%), Dana (France): butterfly (48%), bat (46%)

Inkblot 6: Beck: animal hide, skin, rug, Piotrowski: animal skin, skin rug (41%), Dana (France): animal skin (46%)

Inkblot 7: Beck: human (orange), Piotrowski: none, Dana (France): none

Inkblot 8: Beck: crab, lobster, spider (blue), Piotrowski: crab, spider (37%, blue), rabbit head (31%, light green), caterpillars, worms, snakes (28%, deep green), Dana (France): none

Inkblot 9: Beck: animal: not cat or dog (pink), Piotrowski: four-legged animal (94%, pink), Dana (France): four-legged animal (93%, pink)

Inkblot 10: Beck: human heads or faces (top), Piotrowski: heads of women or children (27%, top), Dana (France): human head (46%, top)

Inkblot 7

Inkblot 8

Inkblot 9

Inkblot 10

Rorschach never intended the inkblots to be used as a general personality test, but developed them as a tool for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. It was not until 1939 that the test was used as a projective test of personality, a use of which Rorschach had always been skeptical. Interviewed in 2012 for a BBC Radio 4 documentary, Rita Signer, curator of the Rorschach Archives in Bern, Switzerland, suggested that far from being random or chance designs, each of the blots selected by Rorschach for his test had been meticulously designed to be as ambiguous and “conflicted” as possible.

The interpretation of the Rorschach test is not based primarily on the contents of the response, i.e., what the individual sees in the inkblot. In fact, the contents of the response are only a comparatively small portion of a broader cluster of variables that are used to interpret the Rorschach data. Other significant information can be gained from the time taken before providing a response for a card (taking a long time can indicate “shock” on the card) as well as by any comments the subject may make in addition to providing a direct response.

Determinants and location are often considered more important than content, although there is contrasting evidence. Determinants are the factors that contribute to establishing the similarity between the inkblot and the subject’s content response about it. They can also represent certain basic experiential-perceptual attitudes, showing aspects of the way a subject perceives the world. Form is the most common determinant, and is related to intellectual processes. Colour responses often provide direct insight into one’s emotional life. Movement and shading have been considered more ambiguously, both in definition and interpretation. Rorschach considered movement only as the experiencing of actual motion, while others have widened the scope of this determinant, taking it to mean that the subject sees something “going on”. More than one determinant can contribute to the formation of the subject’s perception. Fusion of two determinants is taken into account, while also assessing which of the two constituted the primary contributor. For example, “form–color” implies a more refined control of impulse than “color–form“. It is, indeed, from the relation and balance among determinants that personality can be most readily inferred.

Location refers to how much of the inkblot was used to answer the question. Administrators score the response “W” if the whole inkblot was used to answer the question, “D” if a commonly described part of the blot was used, “Dd” if an uncommonly described or unusual detail was used, or “S” if the white space in the background was used. A score of W is typically associated with the subject’s motivation to interact with his or her surrounding environment. D is interpreted as one having efficient or adequate functioning. A high frequency of responses coded Dd indicate some maladjustment within the individual. Responses coded S indicate an oppositional or uncooperative test subject.

“Popularity” and “originality” of responses can also be considered as basic dimensions in the analysis.The goal in coding content of the Rorschach is to categorize the objects that the subject describes in response to the inkblot.

Subject’s responses are categorised into one of 27 established codes. The codes include terms such as “human”, “nature”, “animal”, “abstract”, “clothing”, “fire”, and “x-ray”, to name a few. Content described that does not have a code already established should be coded using the code “idiographic contents” with the shorthand code being “Idio”.