After completing two photographic shoots so far for my Variation and Similarity project, based around the diversity of nature and zooming in on the sublime detail, I have decided to review and reflect my current work:

How well have ideas developed?

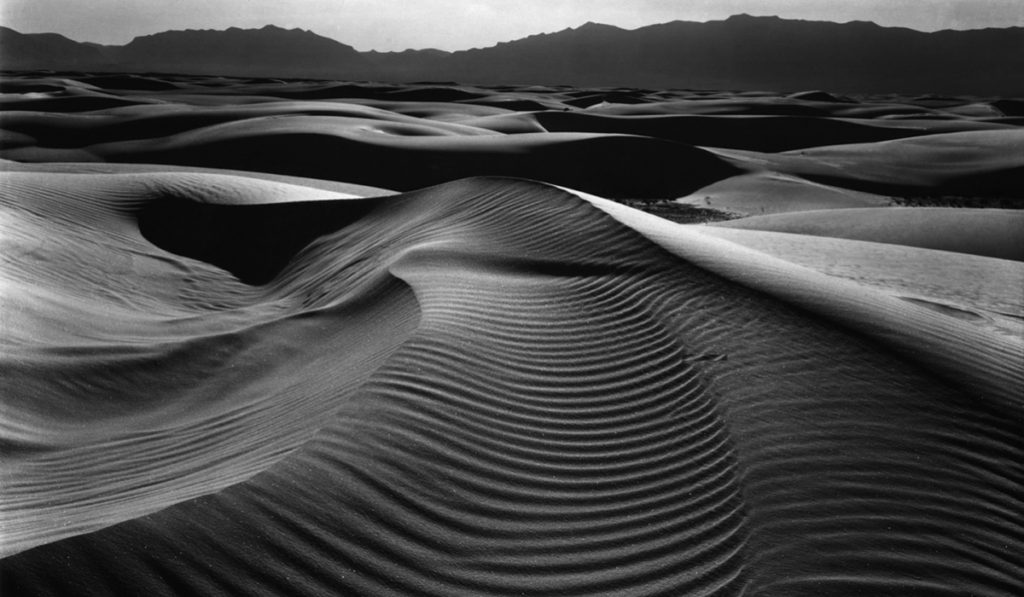

I believe my ideas have developed to a good extent after completing thorough research of photographers, contextual studies and artists before-hand. This research has enabled me to have a clear focal point of zooming in on the four categories of nature I have chosen: water, natural forms, trees and cloudscapes.

Are they sustained and focused?

Creating a 4 shoot photo plan early on in the project has really helped me to photograph what I want in a sustained way. It has given me basic guidelines to follow so I am not taking photographs randomly and unpurposefully.

Are they reviewed and refined?

Giving myself four categories to focus on photographing has helped refine my project, as nature is such a broad spectrum with so many aspects I could look at.

How many responses/ shoots?

I have so far only completed two photographic shoots, but have spent time editing and experimenting so I will end up with the highest quality images possible. I intend to complete at least two more shoots, with additional images if I am unhappy with my edited collection and feel I require more to strengthen my work.

Understanding of composition/ considering quality of light

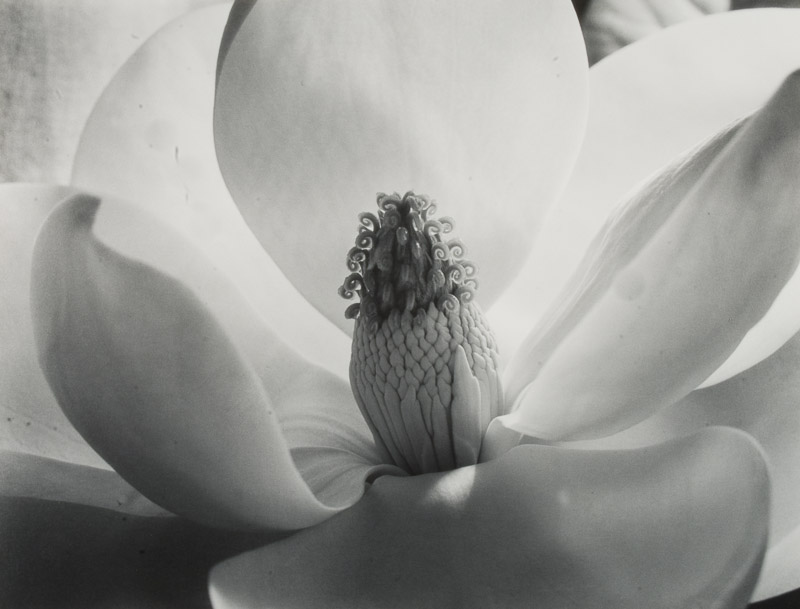

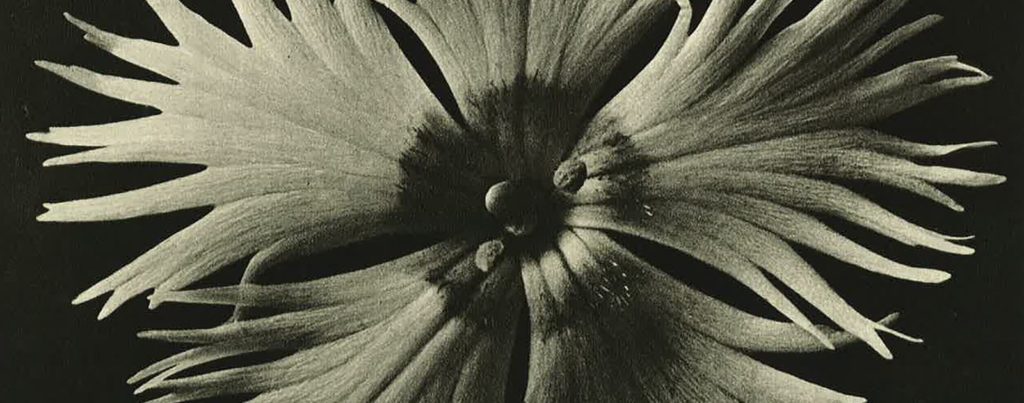

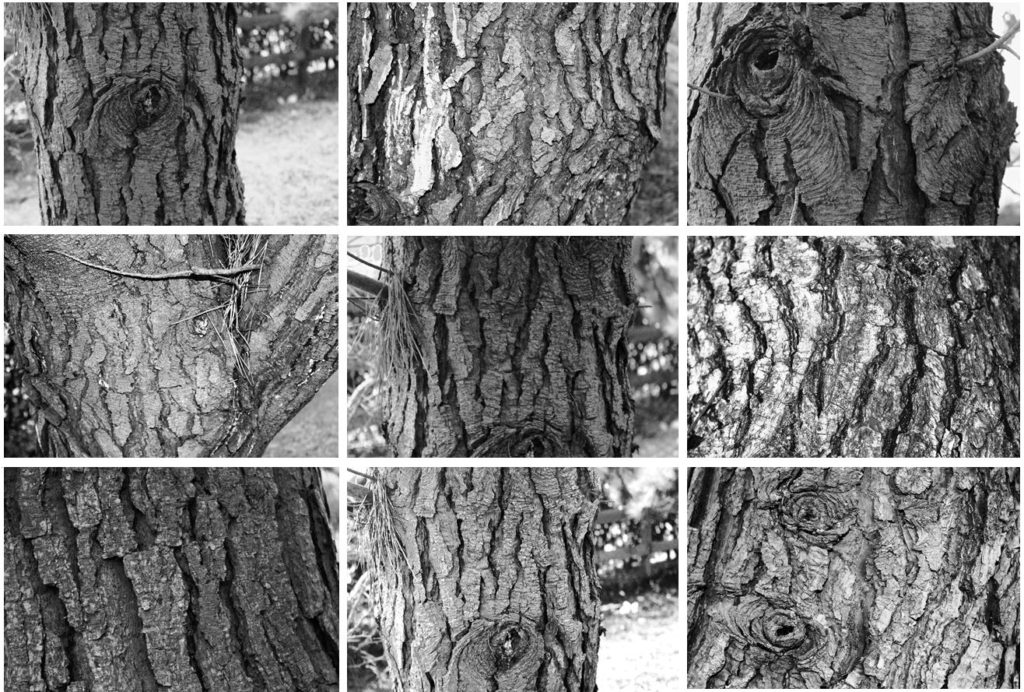

I have completed my first photo shoot in the day time where the light is prime so I could gain the best photographs of trees and bark patterns. My shoot location was in an area of shade due to the large collection of trees, meaning I had to use the optimum amount of light so my photos wouldn’t turn out too underexposed. I completed my second shoot of natural forms early morning as the sun was beginning to rise, and there was sources of natural light I was able to use to highlight the colours and patterns up close of my photographic subjects of flowers and plants.

What are the overall quality of the images?

I am photographing using a Canon 1300d, a camera that produces good quality images. I have experimented with using a range of camera settings, like landscape and close up, white balance and ISO.

How do I respond to research?

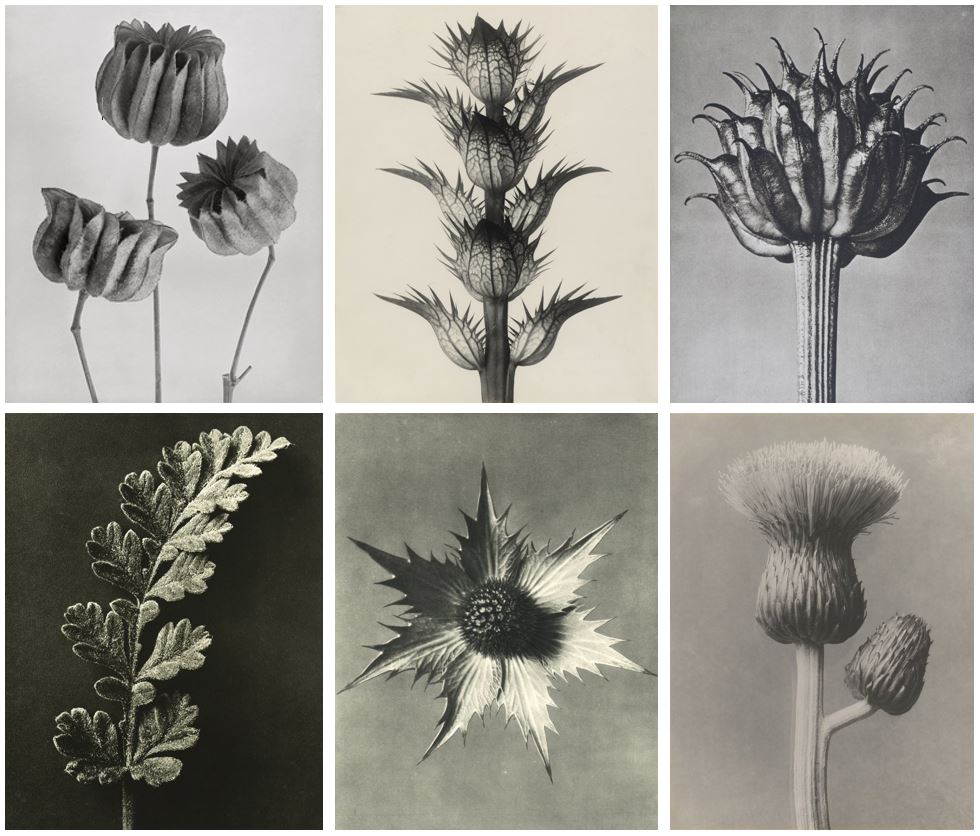

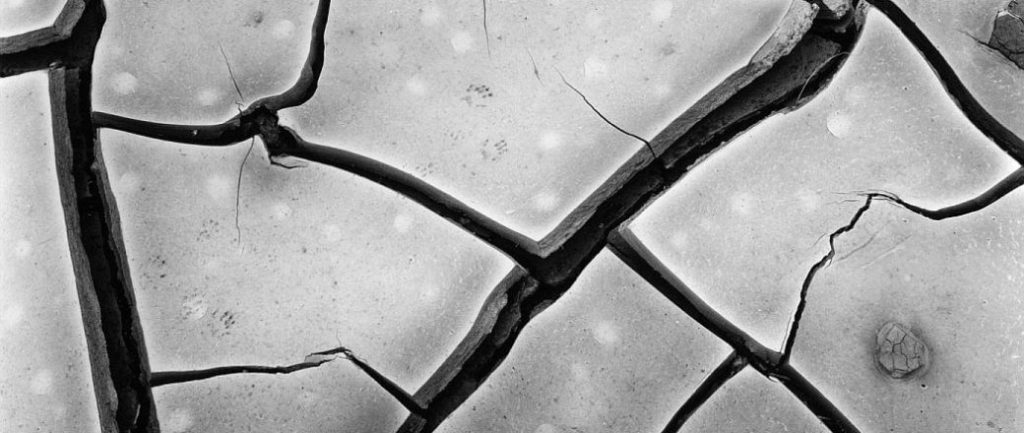

I have conducted research on contextual studies of abstract photography, photo-realism, the sublime, and fine art. This gave me a good pedestal to base my work off and begin photographing from. Looking at and photographing nature so up-close often leads to abstract images focusing on the patterns and colours rather than the form as a whole.

How do I relate to artists references?

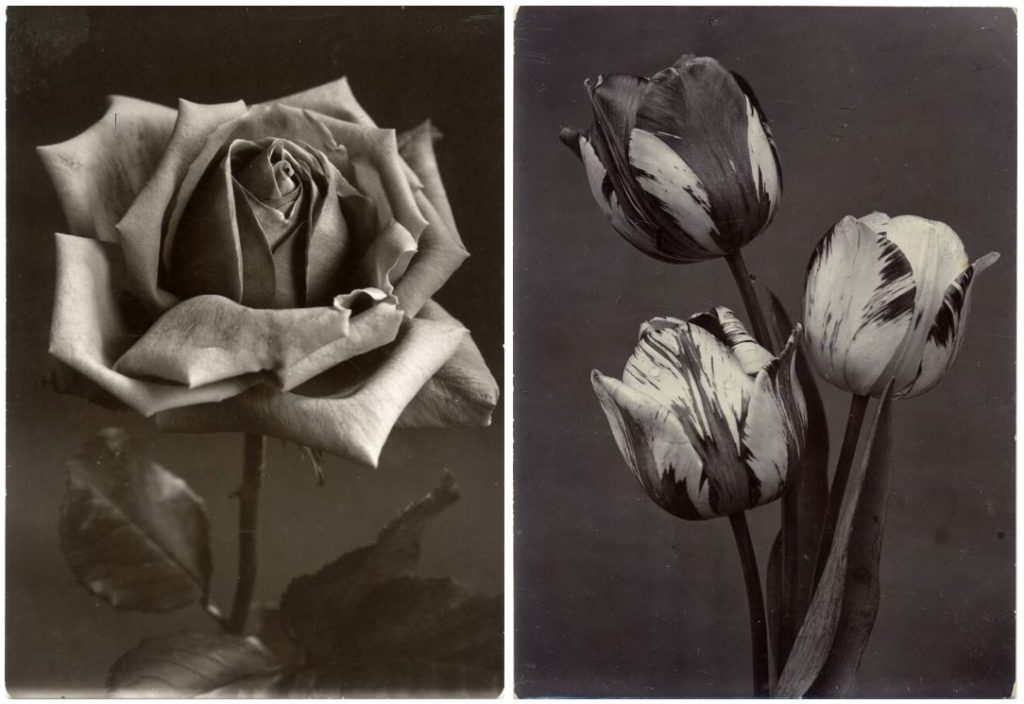

I have been studying a wide variety of artists and photographers, from Hiroshi Sugimoto who I will base my 4th shoot of water on, to Karl Blossfeldt and Charles Jones, who have inspired my second shoot around natural forms. My large source of photographers who I have researched online have enabled me to look at the different ways people have responded to nature in. Instead of taking inspiration from just one artist, I intend to take source from multiple so I get the best final products possible.

How have I interpreted the exam theme?

From the specification title of ‘Variation and similarity’, I have interpreted this within the natural world to zoom in on the environment closely and look at the miscellany of nature and the intricate detail within the sublime e.g. weather patterns, plants. I have looked at mundane things that are passed off as being uninteresting e.g. trees, and have tried to photograph and emphasize the beauty and spiritual nature they hold.

I currently estimate my work to be around a level 3/4 due to having a smaller collection of primary source images, but by the end of my project when I have completed all my shoots I hope to be around a high level 5/6.