David Benjamin Sherry is an American photographer and avid darkroom printer who is challenging and reinvigorating the American Western landscape tradition among other classic genres of photography. His work revolves around interests in the analog film process, environmentalism, color, mysticism, abstraction, human connectedness in the digital age, minimalism and queer politics, and he ultimately aims to reexamine the history of photography. He’s best known for his iconic monochromatic darkroom printed landscapes, a project born from his love of the outdoors and the protected natural landscapes of North America. Eventually these interests developed into new projects, raising deeper concerns for the rapidly changing environment, while continuing to sustain his queer sensibility in the hetero-male dominated canon of photography. Part-archeologist and part-futurist, Sherry uses a large format 8×10 film camera in order to reflect and contemplate our place within the contemporary American landscape.

The revivification and radicalization of the colonial, heteronormative history of American landscape photography—which, ironically, is gorgeous and irresistibly romantic—is David Benjamin Sherry’s modus operandi in Monuments, eight photographs that feature scenes from the National Monuments threatened by the Trump administration. By celebrating and honoring the environmental ethic, kinship with wilderness, and formal mastery of pre-digital, film-based, darkroom photography popularized by Edward Weston, Minor White, Ansel Adams, and Robert Adams, Sherry keeps this heroic tradition alive by communing with far-flung forests and deserts to locate compositions that he transforms into sublime images. But his relationship to the forefathers stops there; his practice conceptually centers itself in education and rejection of perpetuating the corrupt political history of the American West, whose legends of freedom are fabricated from stolen lands which have been “consistently raped, abused, and destroyed,” as Sherry says.

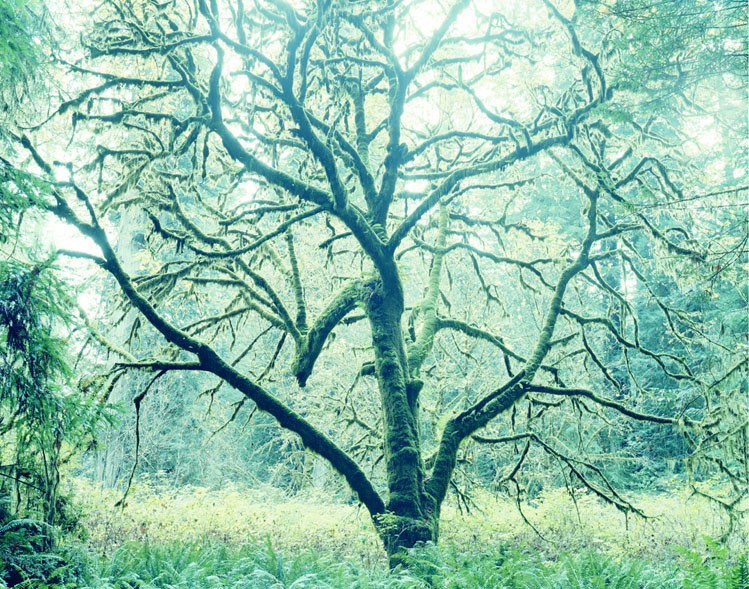

The politics in this exhibition cannot be denied. This series features images of the Trump administration’s final list of National Monuments whose protected status will be illegally violated and “scaled down” to be sold in interest of coal, uranium mining, and oil drilling. While some photographs depict areas slated for imminent development (Muley Point I, Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, 2018), some portray areas that may not be immediately at risk (Rio Grande del Norte National Monument, New Mexico, 2018). In selecting this suite of images, Sherry preferred to openly commemorate the experience of visiting these remote, sacred, ecologically significant places, by choosing to “embody the whole monument” and embracing awareness of, “what’s safe today may not be safe tomorrow.” Oregon’s Cascade-Siskiyou, Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Nevada’s Gold Butte—one gets lost in each image and can physically feel space, vertigo, silence, geological force, weather conditions, and time of day. This is due, in part, to large-format printing and a large-format camera – an 8×10 whose generous negatives can pack more information than high-resolution digital images. But it’s also the result of Sherry’s reverence to place: revisiting his favorite cottonwood tree five times over various seasons or returning to the Grand Staircase – Escalante National Monument over the course of ten years. Adoration and awe are media as much as photography itself for Sherry, who started his photographic exploration of National Parks in 2007 after the death of a close friend to seek the “eternal life around us,” his best photos strike a “quiet equation… that record light over landscape to define form and to find beauty.”

The monochrome printing process Sherry has developed is very much his own — he developed this after mastering “natural or straight” color printing. This process was achieved through the study of color theory and understanding the powerful effect color can have on a viewer. After spending years devoted to black and white photography, Sherry created the monochrome color in his work, as a parallel to the black and white process while even incorporating the zone system. Sherry creates a monochrome hue by using varying degrees on the Cyan-Magenta-Yellow dials on his enlarger, he pushes the color without losing image quality, to achieve the hue that he has actually “pre-visualized” at the moment the photo was taken. Sherry has amassed an archive of color test strips as a kind of reference guide for the system he’s developed for conveying an emotional response, a mood and a tone. For Sherry, monochrome color and black-and-white photography are siblings, because of their “abstraction from reality by highlighting form, light and composition.”

Although humans are absent in these photos, queer narrativity is built into both the process and product via Sherry’s own queer subjectivity. With this environmental work, Sherry aims to disrupt prevailing, institutionally-entrenched understandings of nature and sexuality. Sherry aligns his views with eco-feminism and believes that the destruction of our planet stems from the oppressive forces of the white male hegemony, and that those forces have acted violently against Mother Earth and will continue to do so unless we begin to think differently about our relationship to the Earth and to women and all “others.” Hetero-cis-white male forces, who have controlled our land for centuries, have knowingly forced the ghettoization of these minorities in urban areas, while they control and violate the natural world at will.

Additionally, Sherry considers travel for these pictures to be a tool in understanding the queer experience in mainstream society, as he navigates solo through rural spaces and communities not traditionally considered “safe” for queer people, and is faced with his “otherness” everywhere he goes. “The photo is a vehicle for talking about identity,” says Sherry. By co-opting the formal language and traditional practices of his forefathers while imbuing his finished product with his queer aesthetic and agenda, Sherry presents us with a radical new perspective of the West.

So, while these photographs grapple with grim and angering political circumstance, they paradoxically exude an adventurous, near-psychedelic joie de vivre through his use of color and form: they represent liberation, independence, resistance, and self-determination; American qualities that we supposedly hold dear, but which are constantly imperiled as the land itself. Interconnectedness between identity and the earth becomes Sherry’s poetic call for liberation from the patriarchal power structure that has controlled and abused our public lands for millenia. “With the continued destruction of our planet, we as a society are losing grasp of our deep co-dependence with the earth, and as that connection disintegrates, the key to our survival as a species has also begun to fall apart. Unless we all take action, we are only hastening our own demise.”

Rio Grande Gorge, Rio Grande del Norte National Monument, New Mexico, Monuments, 2018

Traditional Color Darkroom Photograph, 90 × 70 inches

Traditional Color Photograph, 30 x 40 inches

Traditional Color Photograph, 30 x 40 inches

Traditional Color Photograph, 72 x 91.5 inches

Image Analysis:

Traditional Color Photograph, 30 x 40 inches

David Benjamin Sherry captures a seascape in natural daylight, he uses a deep depth of field to capture it entirely in clarity. However, there is a subtle blur due to the sea spray, this covers the land as it disappears into the distance. The purple colour comes in the printing process, where Sherry achieves a range of tones by exposing different areas at different levels. Because of this, the image appears to reach out with a 3D effect in areas where the purple colour is stronger.

Sherry reflects the use of colour in the title of the series, ‘Birth in Futureverse’, obviously believing the World is colourful and that colour represents the differences between us.