Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that produces a cyan-blue print. Engineers used the process well into the 20th century as a simple and low-cost process to produce copies of drawings, referred to as blueprints. The process uses two chemicals: ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. The process was first introduced by John Herschel in 1842, just over three years afterLouis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and William Henry FoxTalbot had announced their independent inventions of photography in silver, using substrates of metal and paper. Sir John was an astronomer, trying to find a way of copying his notes and featured in his paper “On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colours and on Some New Photographic Processes,” . Herschel also gave us the words photography, negative, positive and snapshot. For him science and art were inextricably linked.

The name cyanotype was derived from the Greek name cyan, meaning “dark-blue impression.” The inorganic pigment

Prussian blue, which is the image-forming material of cyanotypes, was prepared first by Heinrich Diesbach in Berlin between 1704 and 1710. Cyanotypes were not widely used until 1880, when they became popular because they required only water for fixing the image.

One of the first people to put the cyanotype process to use was Anna Atkins, who in October 1843 is said to have become the first person to produce and photographically illustrated a book using cyanotypes. The cyanotype to the right is from a book of ferns published in 1843 by Atkins called Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. She was a pioneering figure in photographic history, having produced the first book to use photographic illustrations.

Following Herschel’s death in 1871, cyanotype was appropriated by entrepreneurs of a more commercial turn of mind than its true inventor, and exploited as a reprographic medium, although Herschel himself had previously demonstrated its use for copying text and images.Thee acceptability of cyanotype as a pictorial medium had been seriously inhibited, at least in Britain, by the intolerant response of critics to its powerful colour.

The arbiters of contemporary taste in ‘the art of photography’ were at the time had become accustomed to anaesthetic of monochrome images that were mostly brown, so they declared the unremitting blue of the cyanotype to be anathema. Foremost among these critics was Peter Henry Emerson who said “… only a vandal would print a landscape in red or in cyanotype.” Emerson spent an important part of his life tormented by the debate between those who believed photography could be distilled into a set of hard and fast rules and those who believed that it was a flexible form of expression and impression. In 1886, Emerson began to deliver a series of lectures that defined the correct, naturalistic, way to approach the new medium. He attempted to define an unassailable position in which a photograph should always aspire to represent an artist’s true aesthetic vision, as in the Impressionist painting movement.

John Tennant, the editor of the influential American periodical The Photo-Miniature , conducted quite a spirited defence in one of his issues of 1900:“This prejudice against the blue print because of its color is, in itself, curiously interesting. In every-day life we are inclined to be enthusiastic about everything blue, from the deep blue of the sea or the deeper depths of blue in a woman’s eyes, to the marvellous blue of old Delft ware or the Willow plates of years ago.”

Today we come full circle in witnessing a second revival of the cyanotype process among contemporary photographic artists

Symbolic blue in art and religion

The universal scarcity of blue pigmentation in the natural world, explains why the cyanotype image might have been considered‘unnatural’.

Its low status in photographic art, however, still remainssomewhat paradoxical when we contrast it with the elevated role of bluein the traditions of painting.

The association with the colour of the celestial hemisphere adds anextra dimension to the symbolism of blue. Because it appears in the skyafter the obscuring clouds are dispelled, blue is said to be the ‘colour oftruth’. C J Jung conjectured that:“…blue, standing for the vertical, means height and depth (the bluesky above, the blue sea below).”

In a religious context, blue is the colour symbolising some of theloftiest sentiments: spiritual devotion, heavenly love, and innocence. Inthe traditions of Western religious art, for instance, the Virgin Mary’smantle is invariably rendered in blue, and so is that of Christ during hisministry on earth.

Sabattier effect and Solarization

The Sabattier effect, also known as pseudo-solarization, is a phenomenon in photography in which the image recorded on a negative or on a photographic print is wholly or partially reversed in tone. Dark areas appear light or light areas appear dark. Sabattier effect is sometimes incorrectly referred to as solarization which is an increase in the exposure of a film to light or radiant energy by 10 to 1000 times the normal amount of exposure (4 to 10 f/stops) which leads to the film becoming lighter rather than darker, whilst the Sabattier effect is a manipulation of the printing process in which the print is re-exposed to light midway through the development process.

The Sabattier Effect results in a partial or complete reversal of image tones on either film or paper emulsion, as well as distinctive outlines (known as Mackie lines, after Alexander Mackie who first described them) which border adjacent highlight and shadow areas. It was first discovered in 1862 by Armand Sabattier as a result of an accidental exposure to light during development of a wet collodion plate, producing a partial reversal of tone.

Man ray

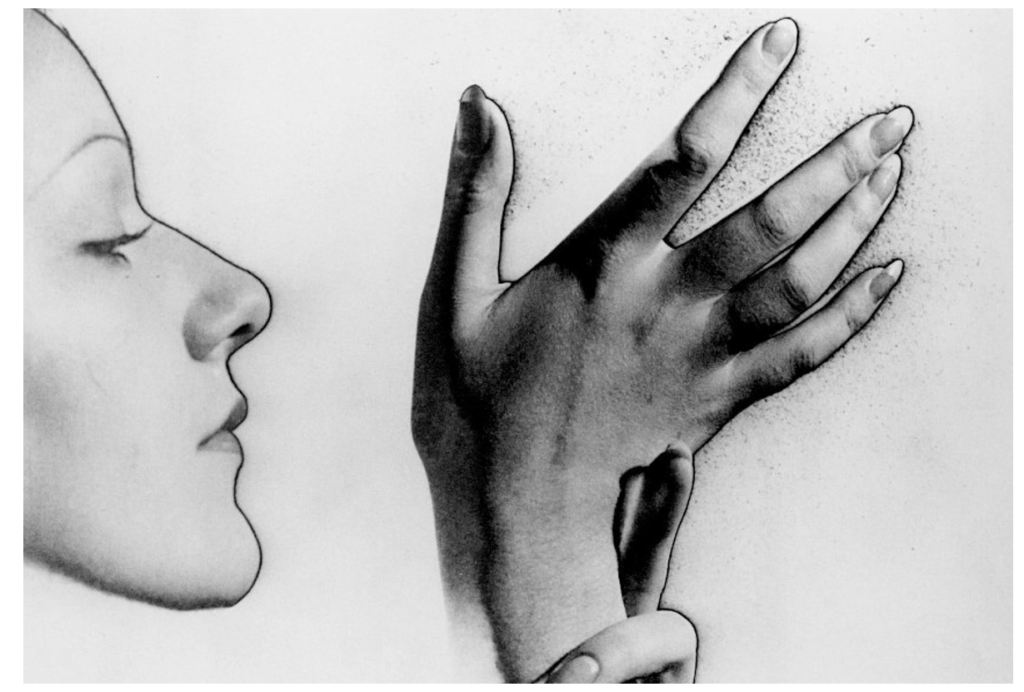

Amongst Paris of the nineteen-twenties, the artist Man Ray, born Emmanuel Radnitzky, expanded the horizons of photography well beyond its representational means, and through relentless darkroom experimentation, liberated that medium from its place as a mirror to nature. His chosen name would come to reflect that mysterious and intrepid realm his photographs occupy in Modern Art.

His experiments with photography included rediscovering how to make “cameraless” pictures, which he called rayographs.

Like a mad scientist, Man Ray conducted a multitude of chemical and optical experiments in his darkroom, exploiting the elasticity of light and its unrealized affects on light-sensitive paper. “I deliberately dodged all the rules,” he once described his method. “I mixed the most insane products together, I used film way past its use – by date, I committed heinous crimes against chemistry and photography, and you can’t see any of it”.

Man Ray claimed to have invented the photogram not long after he emigrated from New York to Paris in 1921. Although, in fact, the practice had existed since the earliest days of photography, he was justified in the artistic sense, for in his hands the photogram was not a mechanical copy but an unpredictable pictorial adventure. He called his photograms “rayographs.”

By placing a variety of translucent and opaque objects directly on the paper during exposure, Man Ray was able to bend and mold that light into abstraction. Left behind was a shadowy imprint of the object’s form, completely dissociated from its original context in his 1922 series, Champs Délicieux. Man Ray’s “Solarizations” shamelessly broke what may have been the golden rule of darkroom photography—Do not turn on the light while in the darkroom. During the developing process, Man Ray would momentarily flicker his studio lights, forming that distinctive inverse of tones around in his subjects.

Man Ray also made films. In one short film, Le Retour à la raison (1923; Return to Reason), he applied the rayograph technique to motion-picture film, making patterns with salt, pepper, tacks, and pins.

Le Retour à la Raison (above) was completed in 1923. The title means “Return to Reason,” and is a kinetic extension of Man Ray’s still photography.