The realities explored in science and spirituality are often assumed to be unrelated to one another. Science explores the outer world with a series of questions beginning with the basic query, “What is this? What is this world all about?” while spirituality begins with the question, “Who am I?”.

In the ancient world these two forms of knowledge were not in conflict but were understood to have a deep and subtle connection. Man’s knowledge of himself complemented his understanding of the universe and formed the basis for a strong and healthy relationship to the creation in which he lived. It is the disconnect between these two types of knowledge that is causing many of the challenges that we face as a global community today.

Ancient wisdom describes human beings as having five layers of experience: the environment, the physical body, the mind, the intuition and our self or spirit. Our connection with the environment is our first level of experience, and one of the most important. If our environment is clean and positive, it has a positive impact on all the other layers of our existence. As a result, they come into balance and we experience a greater sense of peace and connection within ourselves and with others around us. Historically, nature, mountains, rivers, trees, the sun, the moon have always been honored in ancient cultures. It’s only when we start moving away from our connection to nature and ourselves that we begin polluting and destroying the environment.

Religion

While many human beings choose to measure the importance of Nature through economic value or scientific worth, the most difficult of Nature’s gifts to “measure” is its connection to our spirituality. While the spiritual self is not always linked to religion, it is more than relevant to explore the revered place that Nature has been given in so many of the world’s religions.

Christianity tells the story of a paradise on Earth, rightly situated in the beauty of a garden, and documents the efforts of Noah as he’s commanded by God to save two of every species on the planet. Buddhism teaches that all life is sacred. Muslims believe that Nature was given to humans as a gift from Allah. Indigenous cultures all over the world have celebrated the existence of Nature as their “mother”.

Humans & Nature

Japanese Shinrin-yoku had compared how the body reacts to being immersed in nature (woodland), to being in an urban environment. The results of the analysis supported the story told above. Finding that being in the woods was calming, activating the parasympathetic nervous system associated with contentment. Whereas the urban environment stimulated the sympathetic nervous system associated with drive and threat. There’s plenty of evidence that exposure to nature is good for people’s health, well-being and happiness.

Research has consistently shown that increased connection with nature results in decreased stress, anxiety, anger, aggression, depression, and a sense of gloom; while it increases a variety of measures of physical health.

“From the smallest microorganisms to the largest animals, all life on Earth has a common ancestor. Everything is connected to everything. ” Our relationship with nature has historically been one of imbalance and overuse. Nearly every step in human history has unfortunately been accompanied with a leap in environmental degradation. At first, humans were incredibly in-tune with their surroundings. With advancements in technology and agriculture though, humans began to find more efficient ways of sustaining themselves. These advancements allowed for more permanent settlements, which led to rapid population growth and a distancing from nature.

Nature and Mental Health

New studies find evidence in support of what we see clinically. It found that virtually any form of immersion in the natural world, outside of your internal world, heightens your overall well-being and well as more positive engagement with the larger human community.

Exposure to nature has been shown to evoke positive emotions, as well as strengthen individual resilience (Marselle et al. 2013) and coping skills (van den Berg 2010). Getting into nature has been shown to have positive impacts on concentration, learning, problem solving, critical thinking capacity, and creativity as well as enhance mental health and wellbeing through encouraging physical fitness and social engagement.

One study is from the University of British Columbia. It highlights an essential dimension of true “mental health” – the realm beyond healing and managing conflicts and dysfunctions. Mental health includes the capacity to move “outside” of yourself, and thereby Increase and broaden your mental and emotional perspectives about people and life in general. That’s the realm that grows, for example, from meditation – the mindfulness state of being grounded in awareness of the present moment.

Sir David Attenborough talking about Nature and Mental Health

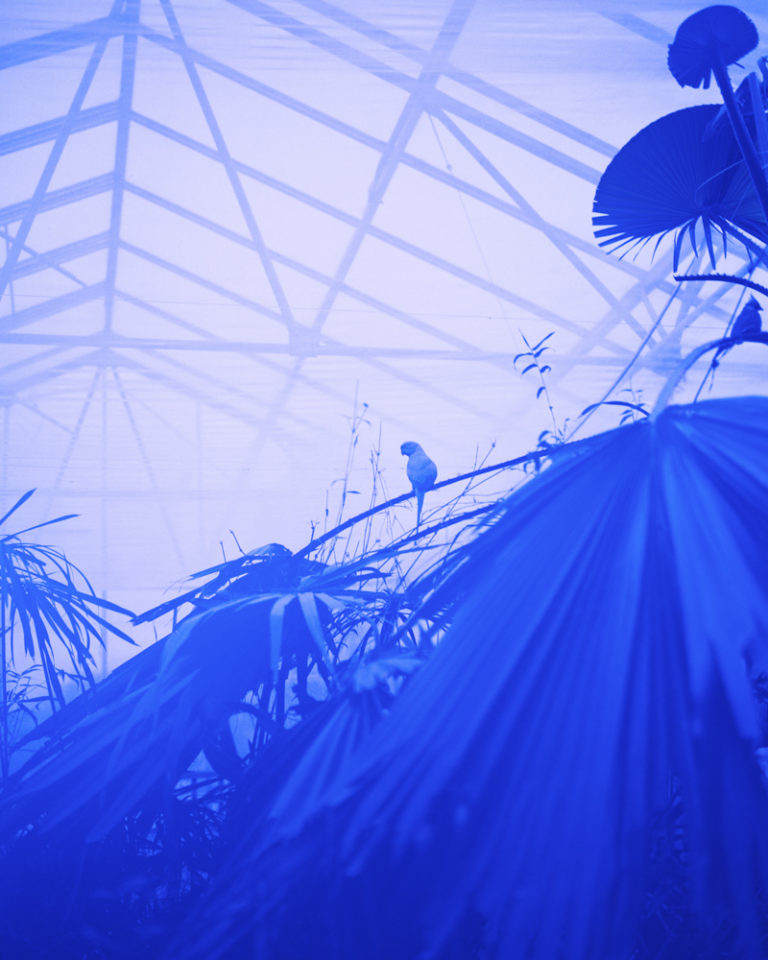

Rinko Kawauchi who i have previously looked at, believes the fleeting nature of these dualities is what ultimately determines our fragile existence. I like how she photographs things that are ‘ephemeral’, that won’t last for long which are unified by an unapologetically sublime aesthetic, a sense of wonder, and by her linking of the earthly and the celestial, the physical and the spiritual. Wassily Kandinsky, who I’ve explored also looks at spirituality in his book ‘Concerning the Spiritual in Art’ where he writes about his beliefs on how art links to humans and spiritual life. “The spiritual life, to which art belongs and of which she is one of the mightiest elements, is a complicated but definite and easily definable movement forwards and upwards. This movement is the movement of experience. It may take different forms, but it holds at bottom to the same inner thought and purpose.”-Kandinsky.

Our Spiritual Connection to Nature: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/our-spiritual-connection_b_648379

http://www.globalharmonycrew.com/nature-and-spirituality-the-earths-role-in-human-happiness

https://www.humansandnature.org/humans-nature-the-right-relationship