Susan Derges (born 1955) is a British photographic artist living and working in Devon. She specialises in camera-less photographic processes, most often working with natural landscapes.

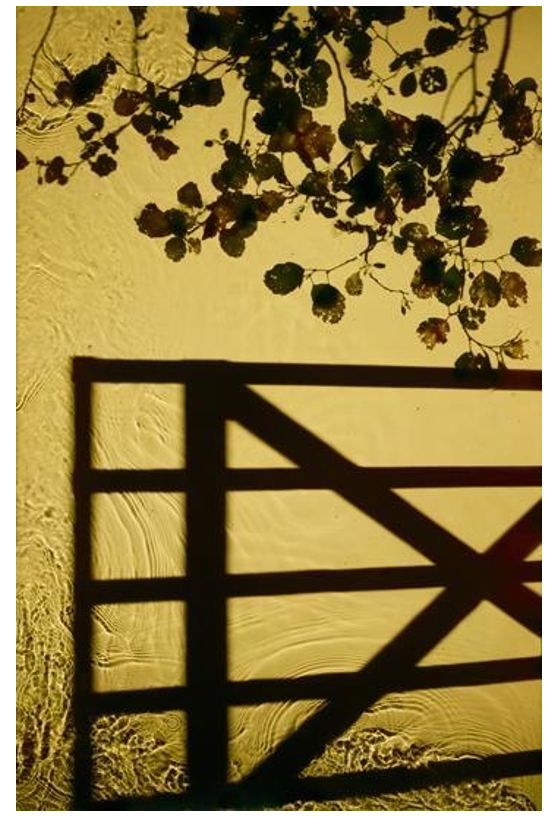

Derges’s 1991 series The Observer and the Observed explored the relationship between object and viewer, and art and science. Propelling a jet of water through the air, Derges used a strobe light to capture the suspended lens-like droplets set against a blurred image of her own face. During the 1990s, Derges became well-known for her camera-less photographs and her pioneering technique of capturing the continuous movement of water by immersing photographic paper directly into rivers or shorelines. Often creating work at night, she works with the light of the moon and a hand-held torch to expose images directly onto light sensitive paper.

Her work revolves around the creation of visual metaphors exploring the relationship between the observer and the observed; the self and nature or the imagined and the ‘real’. Ambient light affects the colour of the images which ranges from blue at full moon to green at new moon. Stormy weather conditions whip up sand in the water, which appears as dark vortices and spirals within the image of the wave.

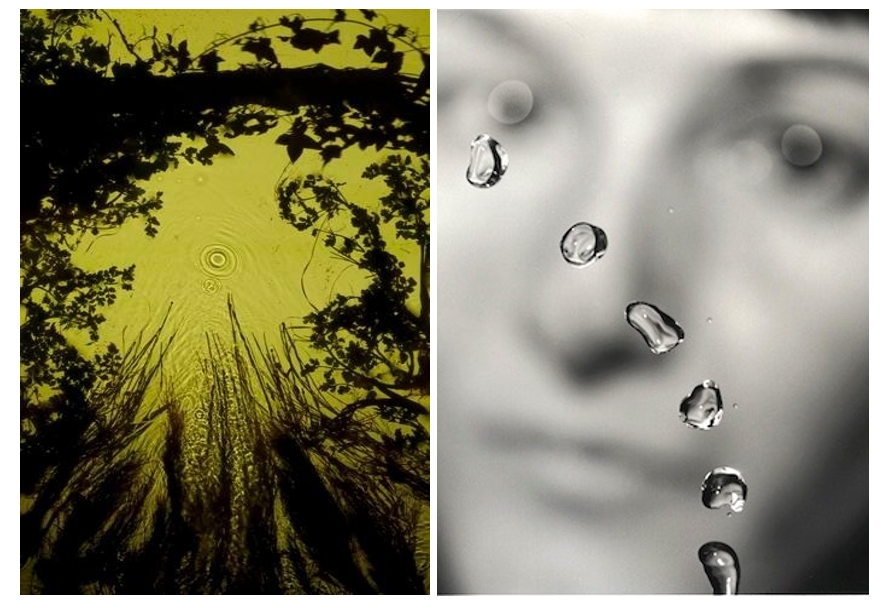

Her 1997 River Taw series exemplified this direct interaction with the landscape. Using the river near her Devon home as a lens, Derges captured fragments of ivy, ice, and debris reflected in or passing through the water.

It was the river Taw that gave Derges the idea that transformed her work. “I was fed up with being the wrong side of the camera. The lens was in the way. I was stuck behind it and the subject was in front. I wanted to get closer to the subject. I had longed liked the idea of the river as a metaphor for memory. The river being a conscious thing containing memories – all the things it carries with it such as rocks, pebbles, shale. It is nature’s circulatory system. I was interested in the science of complexity – mathematical descriptions, information and stimuli, which are supplanted when a more ordered group of descriptions, information and stimuli come in. I was also working with beehives at the time as a model – seeing a connection between how human beings operate and how nature operates – studying the bees was a way of looking at human structures.”

It was working with a waterfall that Derges realised how fully involved she was with her subject matter. When unrolling a print of a waterfall, she was mystified to discover that there were two columns of information recorded. She realised that the second column was actually her fingertips, which had been holding the print in place. She found herself in the arena of her work, actually part of it. “In making the waterfall prints I could not help being part of them.

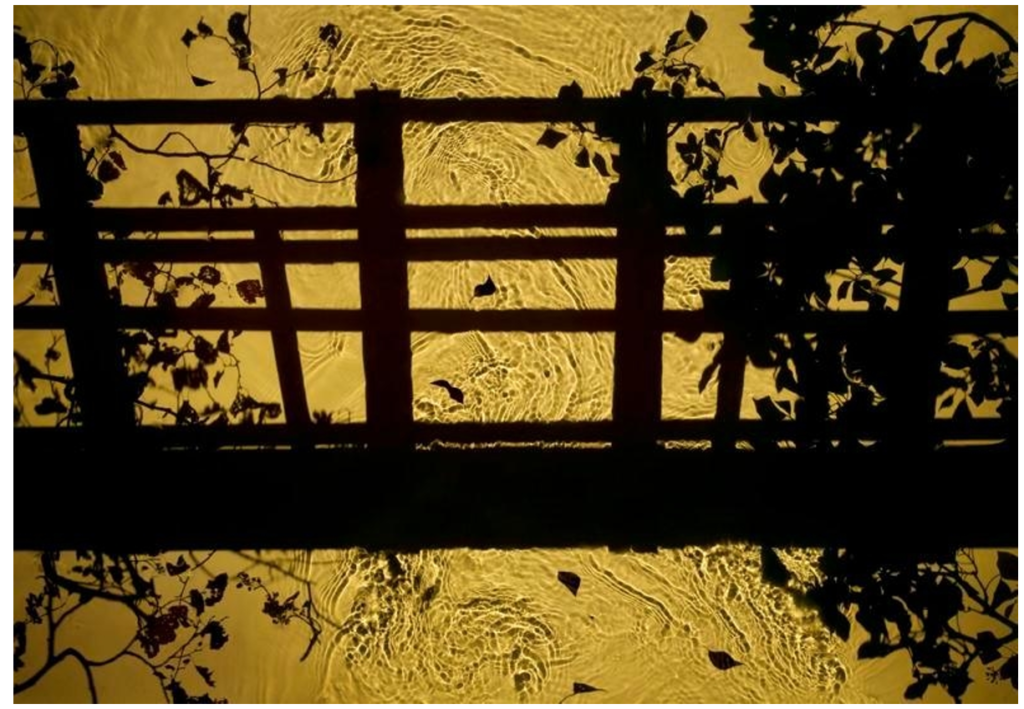

Derges’s images of botanical organisms and flowing water are metaphorically rich, alluding to the connections between ourselves and the natural world. Her 1997 River Taw series exemplified this direct interaction with the landscape. Using the river near her Devon home as a lens, Derges captured fragments of ivy, ice, and debris reflected in or passing through the water.

The structures and bridges in some of her images she stated were made with constructed silhouettes. It’s a reference back to growing up. It’s an imaginary place with the branches brought in. It’s a digital print made with a digital camera.”

Derges expressed an early interest in abstraction because “it offered the promise of being able to speak of the invisible rather than to record the visible”. She turned to camera-less photography after experiencing frustration at the way “the camera always separates the subject from the viewer”. Much of her subsequent work has dealt with this relationship – of separation and connectedness with the natural world. In Derges’ photography, nature imprints patterns and rhythms of motion, growth and form directly on the light-sensitive surface of the photographic emulsion, such as falling water drops etc.

Recently she has begun working in the studio combining analog and digital techniques to create new forms and perspectives hitherto impossible to capture. Her practice reflects the work of the earliest pioneers of photography but is also contemporary in its experimentation and awareness of both conceptual and environmental issues.

Adroplet of mercury lying in the bottom of an upturned speaker cone, which reflects the lens of the recording video camera, is subjected to a sweep of sine waves. The sound disrupts the spherical form of the mercury droplet into ordered shapes of increasingly complex geometrical structures until it passes beyond the range of response of the mercury and the camera ‘eye’ re-emerges on the surface of the droplet.