Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky was a Russian painter and art theorist. Kandinsky is generally credited as the pioneer of abstract art. Born in Moscow, Kandinsky spent his childhood in Odessa, where he graduated at Grekov Odessa Art school. He enrolled at the University of Moscow, studying law and economics.

Kandinsky exploited the evocative interrelation between color and form to create an aesthetic experience that engaged the sight, sound, and emotions of the public. He believed that total abstraction offered the possibility for profound, transcendental expression and that copying from nature only interfered with this process. Highly inspired to create art that communicated a universal sense of spirituality, he innovated a pictorial language that only loosely related to the outside world, but expressed volumes about the artist’s inner experience. His visual vocabulary developed through three phases, shifting from his early, representational canvases and their divine symbolism to his rapturous and operatic compositions, to his late, geometric and biomorphic flat planes of color.

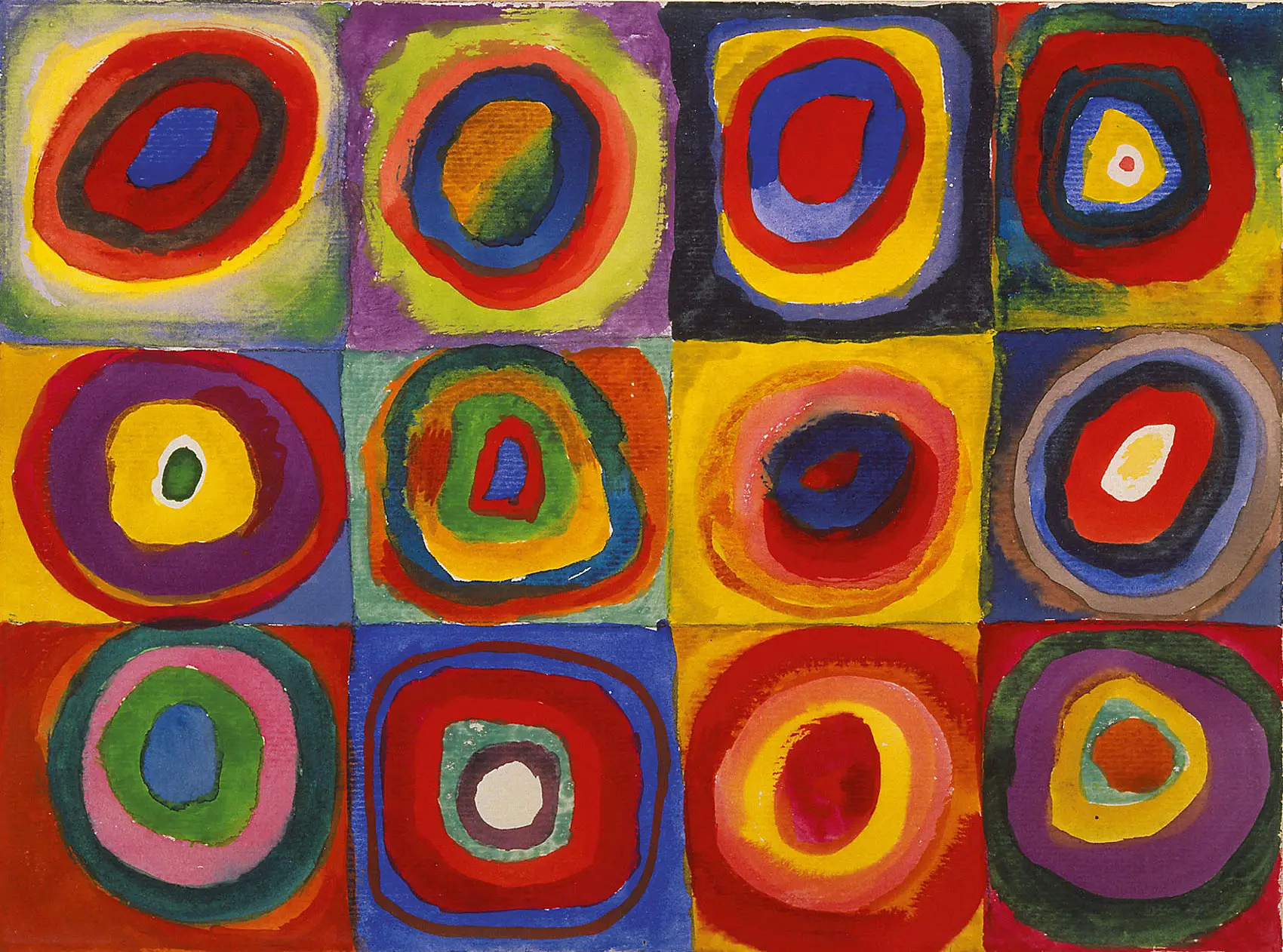

Kandinsky’s most famous pieces are his abstract work, in these examples you can see his frequent use of circles in his paintings. This was another artist of whom sparked or continued that interest in circles in imagery and I would be keen to explore this further and produce responses to these artists.

Squares with Concentric Circles (above) is a small watercolor made with gouache (a type of watercolor paint) and crayon. Kandinsky created a grid composition (the “squares”). Within each square unit, he painted “concentric circles”, meaning that the circles share a central point. He believed the circle had symbolic significance relating to the mysteries of space and he used it as an abstract form to which he would create his art. Kandinsky explores many side-by-side combinations of color relationships: complementary (colors opposite each other on the color wheel, such as orange and blue), analogous (adjacent colors on the color wheel, such as red and orange), and triad (colors spaced equally on the color wheel, such as red, blue, and yellow). He varies the intensity and value of some colors, sometimes even within the same circle. The close placement of such high-value colors makes them appear to pulsate.

The painting is a study, or sketch-like investigation into a subject. Kandinsky’s quick, freehand renderings produce lopsided and irregular geometric shapes, giving the conceptual work a living, organic feel. The watercolors bleed into one another, and the artist sometimes breaks from his formula. He saw the formula as secondary to the study’s purpose, which is the experience of viewing color relationships. Kandinsky never intended for this study to be viewed as a finished work of art, but rather as a color aid to refer to while he worked on other paintings.