Documentary photography; what is it? Is it news for the photographers? Is it imagery with a story, a meaning? Is it boring? Is it powerful? Can it be used to raise issues mainstream media doesn’t? Can it be controversial? Yes.

A document is a piece of paper with important information on; it holds meaning.

A documentary is a programme on TV. It is also a way to convey important information to an audience.

What’s a documentary image? Most people forget about this form of inflicting an emotion onto the viewer but still, it is a powerful source of information – it’s a visual device.

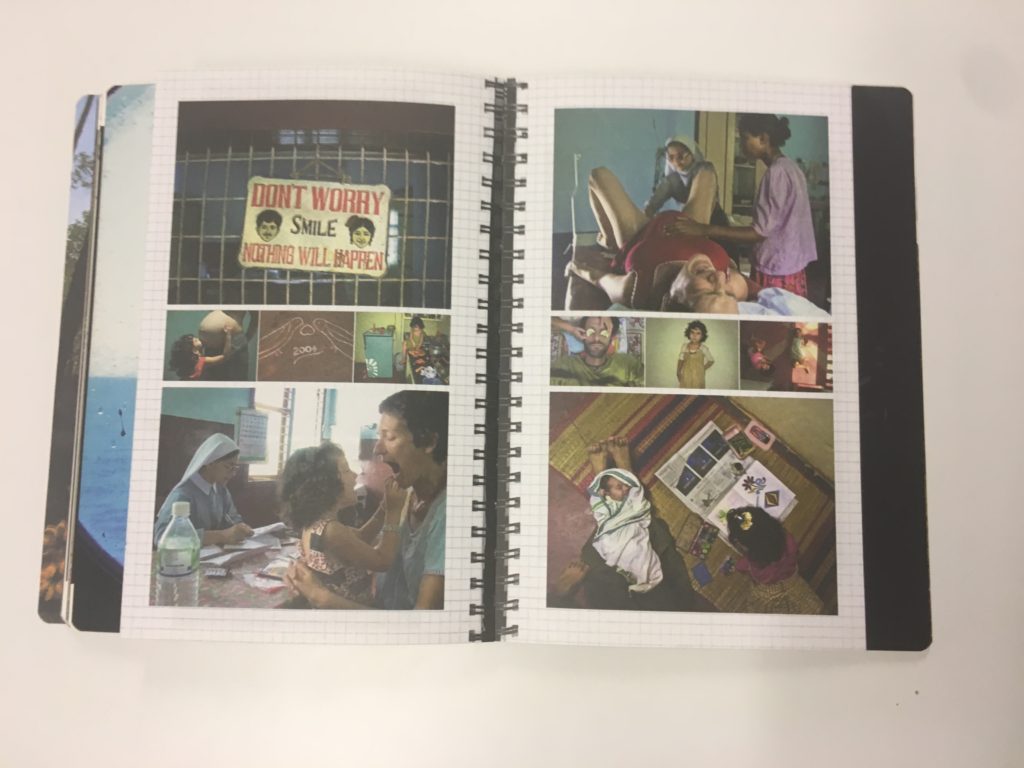

Documentary imagery is a way to derive emotions and feelings from its viewers. It was David Bate, professor of photography at the University of Westminster in London that drew on the idea of documentary photography not just having the ability to record events but also “to enlighten and creatively educate” people about “life itself”. (Bate, D. (2016). Photography: The Key Concepts). There is a certain emotion you can achieve from observing documentary photography that you may not be able to access from contemporary photography, in that documentary imagery can be very captivating due to the context and concept of its being and how an image can tell the story of a person who then becomes the character in a story, much like in a novel.

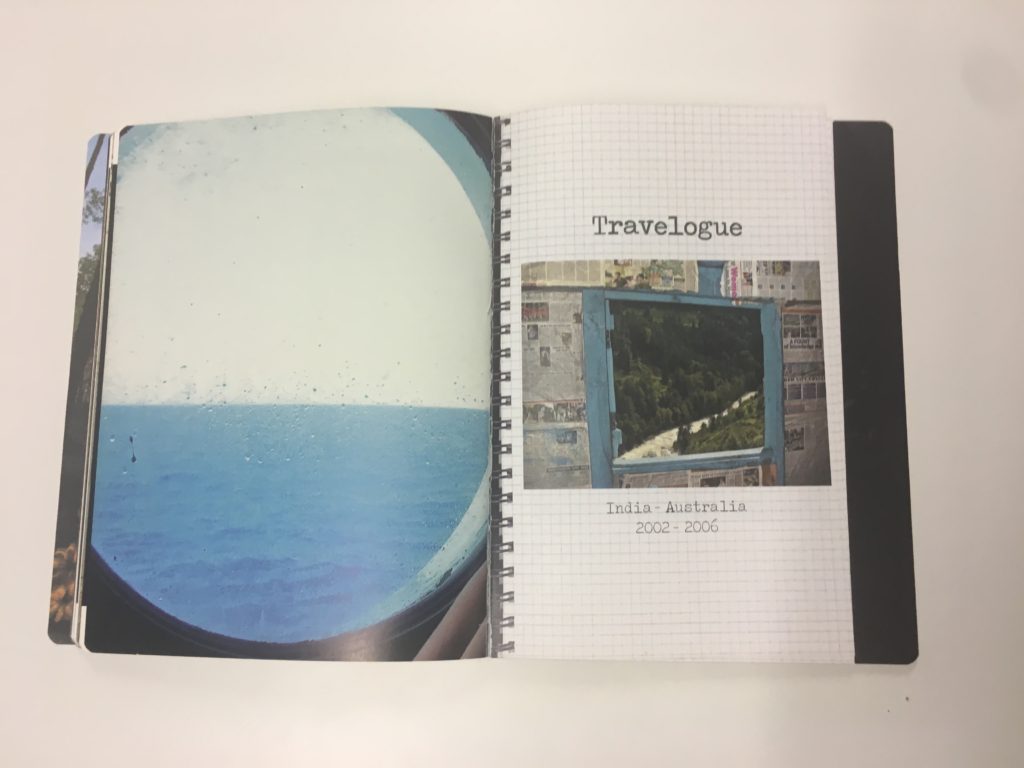

It is difficult to define exactly what is meant by documentary photography because, widely speaking, the concept of photography is challenging to define because there are no set rules to what photography is and how you should go about taking pictures. This is why there are so many pioneers of the art form; especially surrounding documentary imagery. For example, in the first examples of documentary photography, it was used to encourage social reform. However, the first publications of these photos were first forced through by Lewis Hine; an American sociologist and photographer who used his camera to push change in society. He photographed child labour – an increasing problem in the early 1900s. Being part of The National Child Labour Committee, from 1908 and over the next decade of his life, he turned his focus from teaching to documenting child labour hoping to end the practice through his visual stories. I suppose that, looking at documentary photography as a source of powerful storytelling, there is no real need to define what it is. Each photo produced with the intention to “document” is its own visual story and this is what defines not only the medium but also the context of each image – one snap-shot moment can live in history as a utility of social change. It is said that ambiguity in photographs can be used as its strength as opposed to its weakness – a way of encouraging interrogation from viewers as people don’t want to provide direct answers from their work – they want it to provide a feeling, a thought and the confusion that may come is what drives the human mind to look at things differently – Jonny Briggs, a world-renowned contemporary photographer explained his experiment with primary school children in which he asked them whether they like being confused when looking at art. One student response that resonated with me as I feel it is so relevant comment on the fact that being confused allows you to have an argument with yourself. This is what photography is about – interpreting things form your view and although documentary photography was very direct, modernised imagery is not.

Tableaux imagery, much like documentary, is a pictorial narrative and it aims to show a scene which constructs a meaning for the audience, however, the difference being it the format. With documentary photography traditionally used to create a fly-the-wall effect, the photographers aim to subtly show the lives of ordinary people with them often being oblivious to it – it often takes just a click of the camera in order to document that moment in time. Tableaux phtooagrohy, however, constructs a narrative through staging people in a set-up scene to tell a visual story through the particular environment. The style of photography derives from first instances of theatre and art where tableaux was frequently used on stage or in a painting. Tableaux derives from the French term ‘Tableaux Vivant’ meaning ‘living picture’. It was first used to describe a painting or photograph in which characters are arranged for picturesque or dramatic effect and appear absorbed and completely unaware of the existence of the viewer. The difference between documentary and tableaux is that one is in a staged environment and one is ‘real-life’ and therefore, it can be argued that documentary holds more meaning and purpose.

Before radio, film and television, tableaux vivants were popular forms of entertainment in the Victorian and Edwardian era.

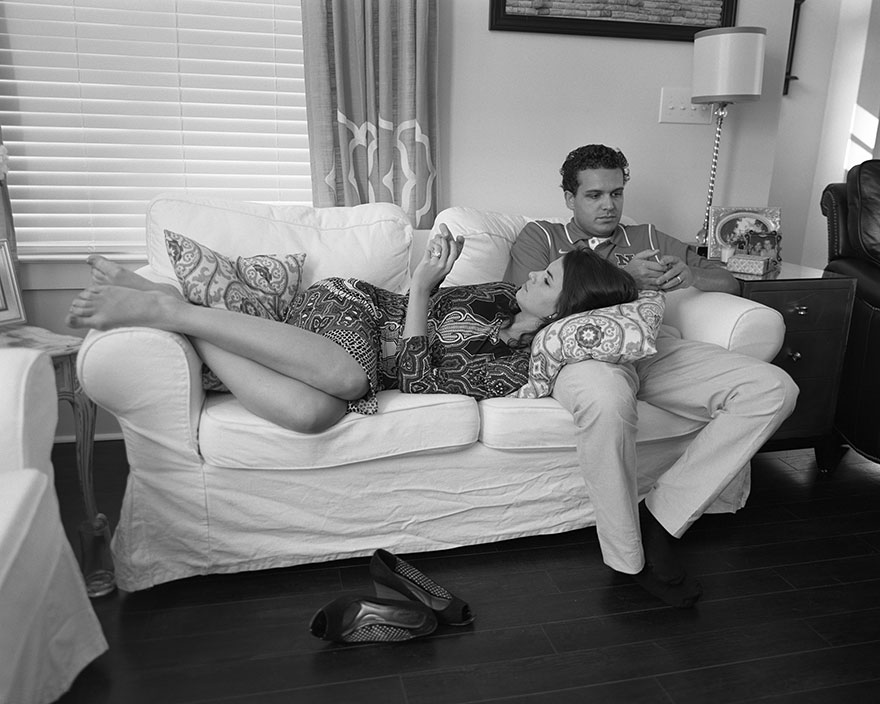

Looking at tableaux photography, and, in particular, the work of Gregory Crewdson, a Brooklyn based tableaux photographer, the style has a very slick and polished effect to them. With regards to documentary photography, composition and framing, or whether one part of the photograph was blurred didn’t really matter or have an effect on the outcome. For a tableaux image to work to its best effect, it is likely it would take much planning to find the best locations and then to pull of the image through trial and error of different poses and set-ups. Gregory Crewdson is known as the photographer with a movie-style budget for casting, locations and make-up and props.

I would argue that tableaux photography aims to romanticise and dramatise the subjects through the use of costumes and how intricately their body positioning is paid attention to and this can however cause ambiguity as the action which is present in the image is not always explicitly presented to the audience, whoever, with documentary, it aims to show in its most raw form, the actuality or what life can hand us.

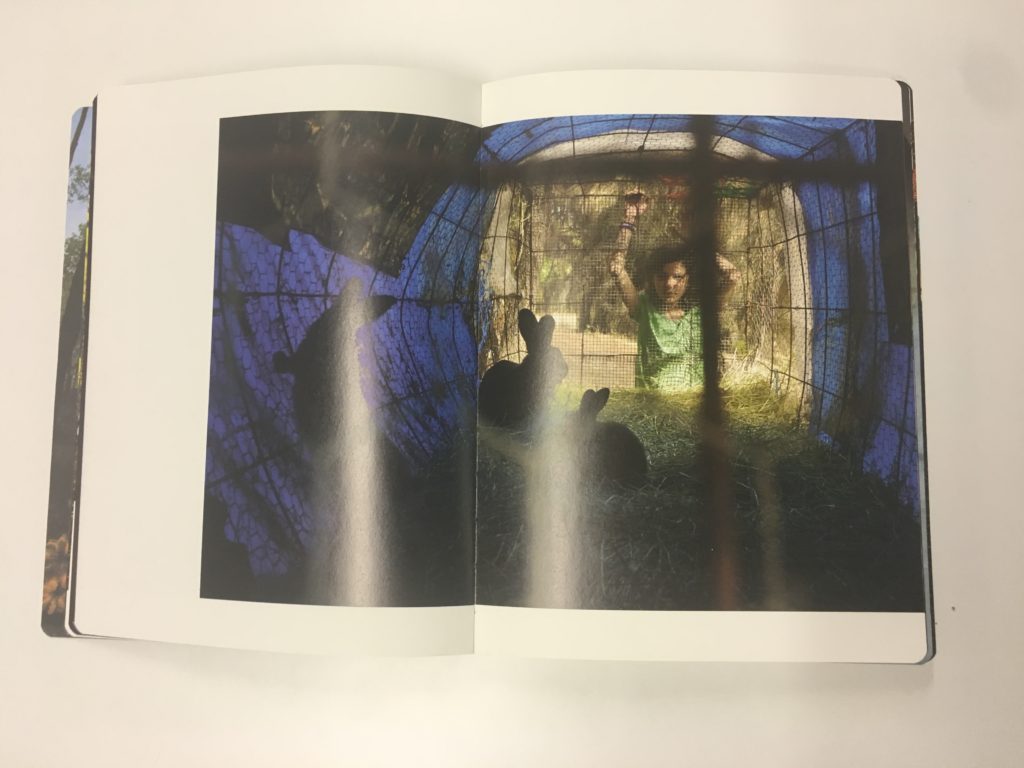

For example, the image above was the first image I took during the shoot and it was mainly an experimental sot to see whether I liked the look of this style. However, I opted not to proceed with this style of the rest of the shot because for me, the image looked to overloaded and it did not have the clean and polished affect I wanted due to the foregrounded object obstructing most of the frame. Even though this was intended, I did not like it at all.

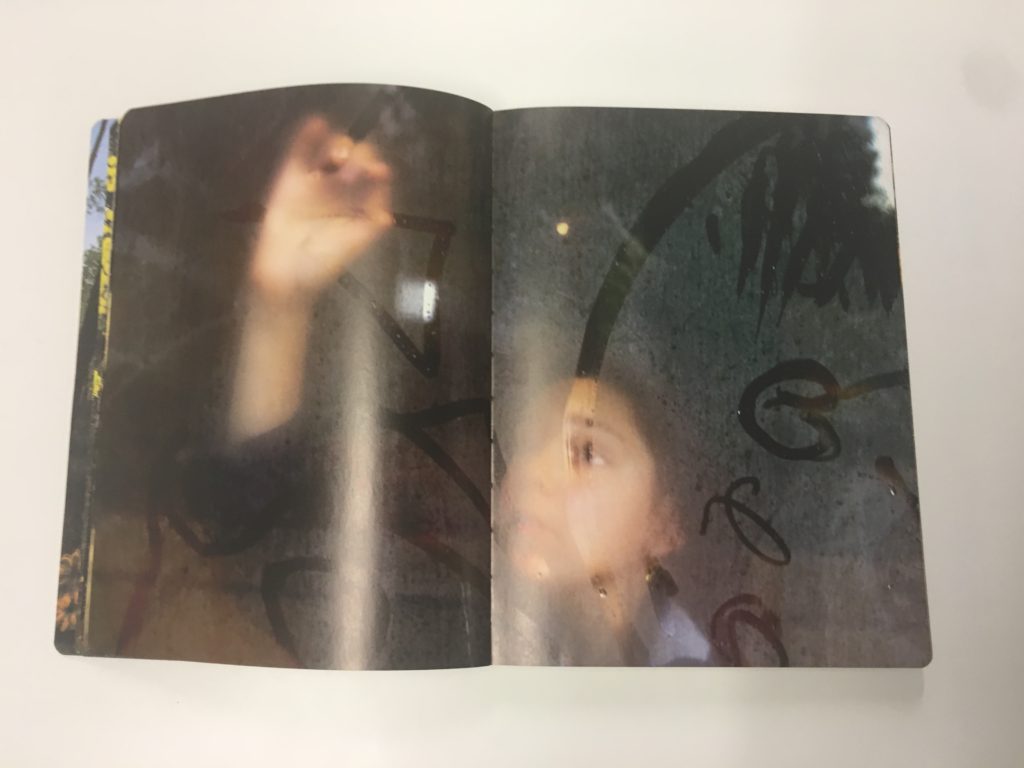

For example, the image above was the first image I took during the shoot and it was mainly an experimental sot to see whether I liked the look of this style. However, I opted not to proceed with this style of the rest of the shot because for me, the image looked to overloaded and it did not have the clean and polished affect I wanted due to the foregrounded object obstructing most of the frame. Even though this was intended, I did not like it at all. Again, this image above was another experimentation that I attempted to do to give a different perspective however, it did not work. I also want the photoshoot to be consistent in the way each shot was photographed, just in different rooms of my house. However, I would not be able to do this in each room that we shot in so this would not be appropriate to show as part of the final images but was useful as an experimentation but the reflection of the window is too over-powering and it fades out the subject.

Again, this image above was another experimentation that I attempted to do to give a different perspective however, it did not work. I also want the photoshoot to be consistent in the way each shot was photographed, just in different rooms of my house. However, I would not be able to do this in each room that we shot in so this would not be appropriate to show as part of the final images but was useful as an experimentation but the reflection of the window is too over-powering and it fades out the subject.