Unlawful Meetings

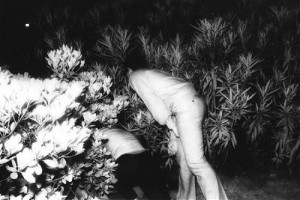

Alike any of the other major religions, Islam seeks to standardize sexual relationships between members of their society or community through moral codes. As laid down in the Quran, any form of sexual behavior – that being: intercourse, oral sex or any action that encourages sexual activity – is strictly forbidden before or outside of marriage. Of course, that doesn’t prevent Muslims engaging in ‘unlawful meetings’, hence the title. In pursuit of romantic love or the sheer fulfilment of mutual desires. Hashim investigates the secret encounters that take place between young Muslim lovers in parks, hidden between trees, or under the cover of the night on beaches and in parking lots. Using night vision cameras, inconspicuous smartphones or digital cameras equipped with long-range telephoto lenses, she captured couples enjoying moments of the greatest intimacy in very public spaces in Sweden swell as in Denmark.

“Those who come from a Muslim background follow strict rules that subsume their individuality, so that the true self is rarely revealed. The public persona and the private life are two distinct zones, creating paradoxes in everyday life that lead to a form of cultural schizophrenia.’”

Hashin’s build in tension and suspense between the public and the private spheres, which runs more acutely through the lives of these young Muslims than of their non-Muslim peers, is reflected in “Unlawful Meetings”. It lies in the invisibility these lovers enjoy in public; for the most part, passersby turn a discretely blind eye to the privacy they create for themselves in shadows and parked cars at nights. This idea of truthfulness and abiding by the rules and guidelines set out for them bombarded the natural path set out for them by there deliberate ancestors. Hashim ensures the anonymity of her subjects, and thus the lawfulness of her recordings of their acts, by leaving out colors and by never showing more than 25% of their facial features. Yet what cannot be hidden is the passion, which, according to one of the youths she interviewed, is heightened exactly for being so “secretly and so rarely enjoyed”. For Hashim herself, who identifies as a believing, but not a practicing Muslim, the project has led her to revisit the tenets of her faith as laid down in texts written in times so fundamentally different from today. Convinced that the ban on sex before marriage was written to protect women and their offspring, she wants to put up for discussion the question if contemporary women and men can’t find other options – in terms of health, or legal and financial security for themselves and their children – to take care of themselves.

Hashim uses the form of a fan-fold laporello in order to tell the story from a dual perspective. On one side of the laporello, shows the images taken with a night-vision camera and the other revealing grey-scale images using a long range telephoto lens. I feel this idea is really interesting and if I was to recreate this in terms of my project I’d use the traditional rituals of love on one side and the non-traditional (online dating) in order for the reader to visually the changes which have occurred over time in means of relationship commodities.

Throughout Hashin’s enduring project, she adopts the professional distance of the social anthropologist conducting a field study, yet at the same time there is an inescapable sense of surveillance and ghoulishness parallel to the work of Kohei Yoshiyuki. In the photographic act again we find the two zones of distance and proximity intertwined in a way that many viewers will find disturbing in its ambiguity.

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Alike Hashim, the reader can be reminded of Kohei Yoshiyuki’s infrared-lit photographs from the 1970s, which capture Japanese couples engaged in night-time sex, surrounded by spectators hidden in pitch-dark public parks. But Hashim believes Unlawful Meetings is quite different, because of the community it depicts.

“A lot of white Danish people live here,”

Hashim says.

“So whenever I see darker skinned people, I’m already guessing that they meet here secretly, because they know that their families won’t find them here.”

Hashim, however, does find them. Hiding in public toilets, behind trees and in cars, photographing the Muslim couples who meet in secret, engaging in forbidden sexual acts in bushes and cars. Hashim’s photos are often blurry, the subjects partially obscured by the leaves of a tree or car doors that cover the people’s faces, though this is intentional: Hashim wants them to remain anonymous.

“The way these people met, the way they felt and the way they touched is still visible in these photos. You don’t always need to capture a face to depict emotions.”

Written by Colin Pantall

Lina Hashim’s photography has its roots in her own childhood, in which the grand themes of family, conflict, exile and migration read like a checklist of documentary topics.

“When the Iraqis came into Kuwait, my father, who had been imprisoned in Iraq for his communist activities, was on the list of people they wanted to take to jail. He was frightened, so he ran,”

Lina tells the British Journal of Photography.

“When I was a teenager, I wasn’t allowed to have boyfriends or intimacy with anyone before getting married, and it was the same thing with my sisters and my brothers and everyone in the community,”

says Hashim.

“But my friends told me about places where they could go to meet their boyfriends, and they said I could go there with them, just to join them, and then I could maybe meet somebody there. It was always in parking lots, or by the sea, or the forest, or the kind of places where you take a dog for a walk. That’s actually how the project started.”