Picasso and the Art World

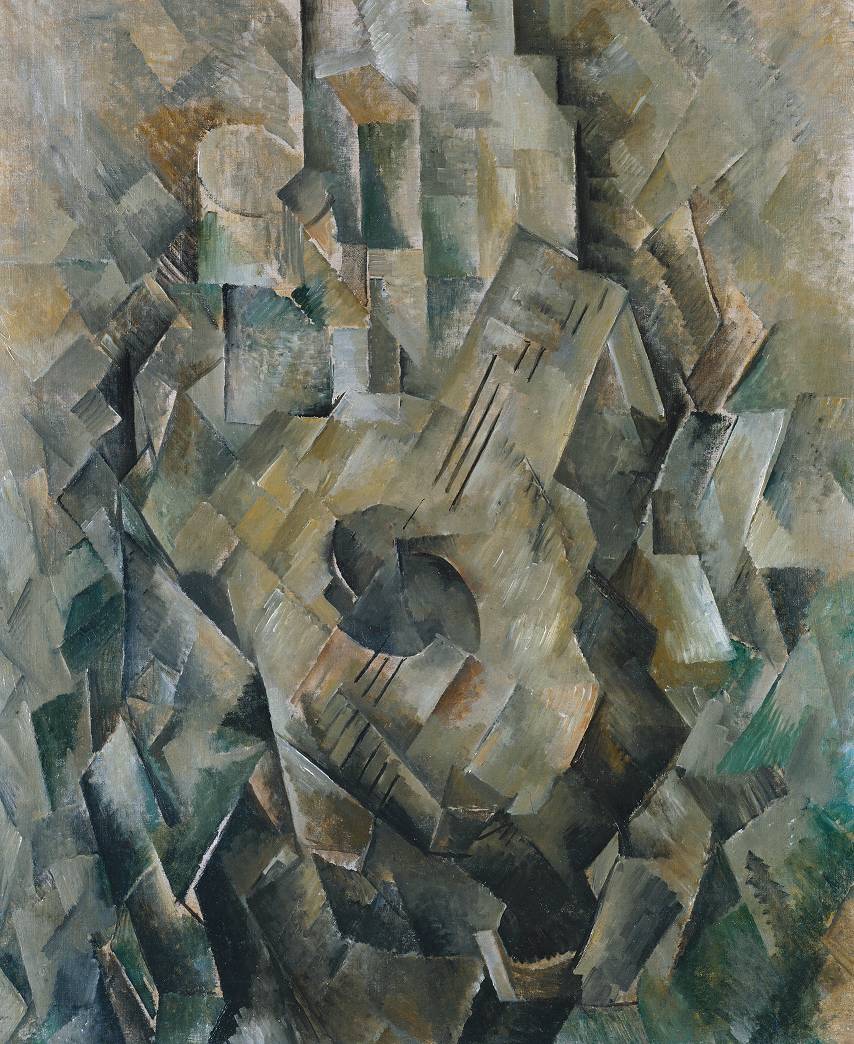

Pablo Picasso was one of the most dominant and influential artists of the first half of the twentieth century. Associated most of all with pioneering Cubism, alongside Georges Braque, he also invented collage and made major contributions to Symbolism and Surrealism. Below displays some of the major influence Braque had on Picasso, as their styles are easily suggested as similar.

He saw himself above all as a painter, yet his sculpture was greatly influential, and he also explored areas as diverse as printmaking and ceramics. Finally, he was a famously charismatic personality; his many relationships with women not only filtered into his art but also may have directed its course, and his behavior has come to embody that of the bohemian modern artist in the popular imagination. This ‘imagination’ fits in well with how love was a greatly prominent part of Picasso’s artwork. This became clear during much of Picasso’s work as the female’s pictures in his series’s dictated the perception of women of the time, contextualising his representation of art.

Picasso first emerged as a Symbolist-influenced by the likes of Edvard Munch and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. This tendency shaped his so-called “Blue Period”, in which he depicted beggars, prostitutes, and various urban misfits, and also the brighter moods of his subsequent ‘Rose Period”.

Also, there where a confluence of influences from Paul Cézanne and Henri Rousseau to archaic and tribal art, encouraging Picasso to lend his figures more weight and structure around 1906. And they ultimately set him on the path towards Cubism, in which he deconstructed the conventions of perspectival space that had dominated painting since the Renaissance. These innovations would have far-reaching consequences for practically all of modern art, revolutionizing attitudes to the depiction of form in space.

Picasso’s immersion in Cubism also eventually led him to the invention of collage, in which he abandoned the idea of the picture as a window on objects in the world, and began to conceive of it merely as an arrangement of signs that used different, sometimes metaphorical means, to refer to those objects. This too would prove hugely influential for decades to come.

Picasso and ‘Truth’

Picasso claims that Art is not considered ‘truth‘ or more in-fact ‘earnest‘. Art in Picasso’s world is considered a ‘lie‘ that makes people envisaging Picasso’s art ‘truth‘. Margritte’s painting ‘La Trahison des Images‘, in which he painted a picture of a pipe with the words “C’est n’est pas une pipe“, goes some way towards an explanation. Art is not considered a reality but can however, examine and model reality.

Picasso uses art to use as a mask to cover up usual perceptions of everyday life. Picasso famously said:

“We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realise truth”.

Picasso’s outlook of art explores the varied perception of the reader on his pieces. This outlook on an audience gives Picasso a reason to illustrate subjects like love in a way people perceive the truth of an artwork.

The Cubist Revolution: Picasso’s Strife to change Art History

Picasso discussed in an interview with The Guardian

Art journalist Jonathan Johns explores Picasso’s art in the light of truth and the beauty behind his ideology.

“Picasso’s eyes perceived the infinite complexity of life”.

Within the interview, Jones focuses on the evolution of Picasso as an artist, and the way he has set his own guidelines to work against. His first work, “Brick Factory at Tortosa“, is “an experiment in how brutally you can reduce, simplify, solidify and abstract forms and still produce a picture that is not simply recognisable, but profoundly full of life.” It is a study in dryness and heat. The factory’s buildings and chimney offer Picasso perfect, geometric shapes to play with. Picasso’s simplistic form of art

Picasso and Braque

Brick Factory in Tortosa was a quiet moment during the revolution, and Picasso, together with Braque, moved rapidly towards the style that is already being nicknamed (in a review of Braque’s new paintings in spring 1909) “cubism“. The word denotes a way of seeing already manifest in Picasso’s brick factory: “the systematic transformation of surfaces into planes of colour, their jarring arrangement in rough geometries, the harshness of palette“. As a reader you can see very clearly how much Picasso and Braque owed to their discovery of Cézanne’s landscapes. The brick factory in the heat has the toughness of Cézanne’s Provencal rocks – but it has a 20th-century quality that makes it different. Factories had only been acknowledged by 19th-century landscape painters as smokestacks in the distance. Picasso looks the modern world squarely in the eye.

In the months to come he and Braque will bring their revolution further into the open and by 1910 Picasso will be painting such masterpieces as his Portrait of Kahnweiler.

It is the centenary of Picasso’s factory and of the naming of cubism – a centenary marked by a new triumph for Picasso, as for the first time he gets an exhibition at London’s National Gallery. Picasso: Challenging the Past will concentrate on his fascination – full of rivalry and respect – with the great tradition of European art. I’m looking forward to it but I hope it won’t make him too respectable. Picasso was a rebel and it will be a long time before his art settles into history enough for him to be caught in the toils of that horrible expression, “old master”. Picasso’s eyes stare into our time and challenge us. Where’s our cubist revolution?