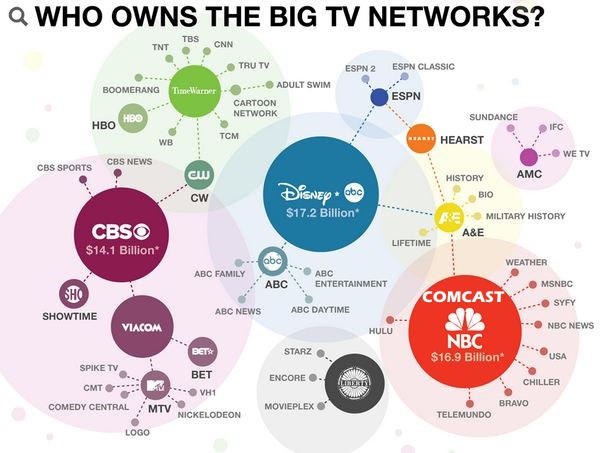

- Media concentration / Conglomerates / Globalisation (in terms of media ownership)

A media conglomerate, media group, or media institution is a company that owns numerous companies involved in mass media enterprises, such as television, radio, publishing, motion pictures, theme parks, or the Internet

- Vertical Integration & Horizontal Integration

Horizontal integration is when a business grows by acquiring a similar company in their industry at the same point of the supply chain. Vertical integration is when a business expands by acquiring another company that operates before or after them in the supply chain.

- Gatekeepers

Gatekeeping is a process by which information is filtered to the public by the media. … This news perspective and its complex criteria are used by editors, news directors, and other personnel who select a limited number of news stories for presentation to the public. someone who allows information that they deem fit so someone with a lot of power.

- Regulation / Deregulation

a process in which a government removes controls and rules about how newspapers, television channels, etc. are owned and controlled: Critics of media deregulation say it can give too much power to individuals who own many forms of mass media.

- Free market vs Monopolies & Mergers

The free market is an economic system based on supply and demand with little or no government control. Cross ownership: ownership of different kinds of media (TV, newspapers, magazines, etc.) by the same group. Monopoly “in cross”: reproduction into local level, of the particularities of cross ownership.A media merger is defined in the Act as: • a merger or acquisition in which 2 or. more of the undertakings involved. carry on a media business in the. State; or.

- Neo-liberalism and the Alt-Right

- Surveillance / Privacy / Security / GDPR

David Hesmondhalgh is among a range of academics who critically analyse the relationship between media work and the media industry. In his seminal book, The Culture Industries (Sage, 2019) he suggest that:

the distinctive organisational form of the cultural industries has considerable implications for the conditions under which symbolic creativity is carried out’

The Culture Industries (Sage, 2019, p.99)

Put another way, in an article he wrote with Banks (Banks, M., & Hesmondhalgh, D. (2009). Looking for work in creative industries policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 415-430.)

there must be serious concerns about the extent to which this business-driven, economic agenda is compatible with the quality of working life and of human well-being in the creative industries.

Looking for work in creative industries policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy p.428

A critical reflection that highlights the ‘myth-making’ process surrounding the potential digital future for young creatives, setting up a counter-weight against the desire of so many young people who are perhaps too easily seduced to pursue a career in the creative industries. Where the promise of wealth and fame and the celebration of a range of unlikely popular heroes including various dot.com millionaires, Young British Artists, celebrity chefs, pop stars, media entrepreneurs and the like, have according to Banks and Hesmondhalgh (2009), encouraged nascent creatives to imagine themselves as the ‘star’ at the centre of their own unfolding occupational drama. Put precisely,

As can be deduced, this approach looks to spotlight a prevailing assumption around cultural production as one that is ‘innately talent-driven and meritocratic – that anyone can make it’ (ibid).

Although, as Angela McRobbie (2002) (2016 ) and others, (Communian, Faggian, & Jewell, 2011); (O’Brien, Laurison, Miles, & Friedman, 2016); (Hesmondhalgh, 2019) have argued, the study of creative work should include a wider set of questions including the way in which aspirations to and expectations of autonomy could lead to disappointment and disillusion.

As Banks and Hesmondhalgh argue,

in its utopian presentation, creative work is now imagined only as a self-actualising pleasure, rather than a potentially arduous or problematic obligation undertaken through material necessity (2009, p. 417)

As Hesmondhalgh (2019) notes, one feature of cultural work in the complex professional era is that many more peole seem to have wnated to work professionally in the cultural industries than have succeeded in do so. Few people make it, and surprisingly little attention has been paid in research to how people do so, and what stops others from getting on.’ (p.99)

In my own research, I looked at theories of the self and identity in relation to aspirational ambitions and the realities of the creative economy which can often be found to out of kilter.

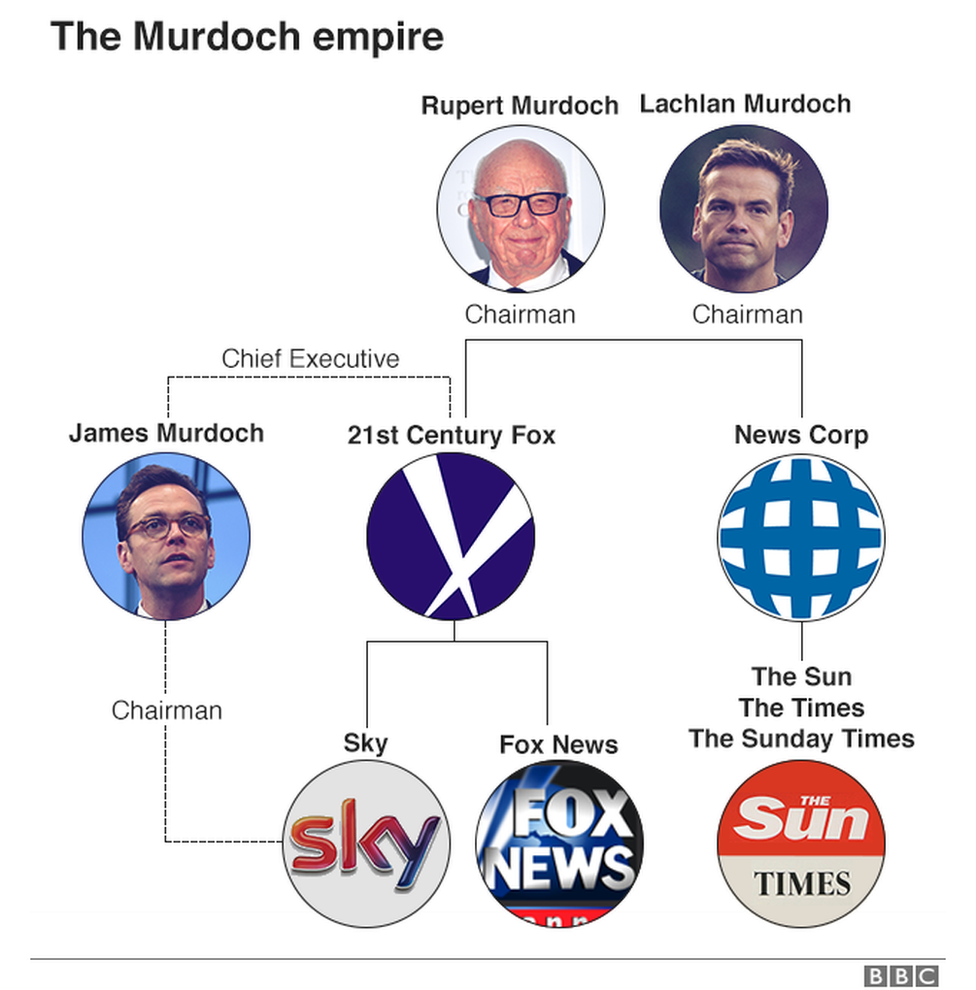

Murdoch media empire