Editing – Iona

Sound – Noah

Cinematographer – George

Director – Aaron

Screenwriter – Collaborative

Editing – Iona

Sound – Noah

Cinematographer – George

Director – Aaron

Screenwriter – Collaborative

Billy Wilder’s 1950 film Sunset Boulevard and Dan Gilroy’s 2014 film Nightcrawler distinctively utilise the film noir subgenre’s stylistic and narrative conventions. Both are incredibly cynical and gritty in tone, with Nightcrawler exploring the violent underbelly of urban America, whereas Sunset Boulevard delves into the destructive nature of fame and Hollywood. These films have been chosen for comparison due to the contrasting contexts in which they were made, Sunset Boulevard being a classic 1950s Hollywood noir film and Nightcrawler being a modern-day neo-noir, both emphasising differing social issues of the time. Wilder’s film follows an aging silent film queen that refuses to accept that her stardom has ended. She hires a young screenwriter to help set up her movie comeback, however his ambivalence about their relationship and her unwillingness to let go leads to a situation of violence, madness, and death. Nightcrawler follows low life thief, Louis Bloom, as he discovers a new way to earn money, by capturing photographs of crime scenes. Resorting to extreme measures to get them that results in violence and destruction.

Key narrative and technical conventions of the French New Wave approach to film making:

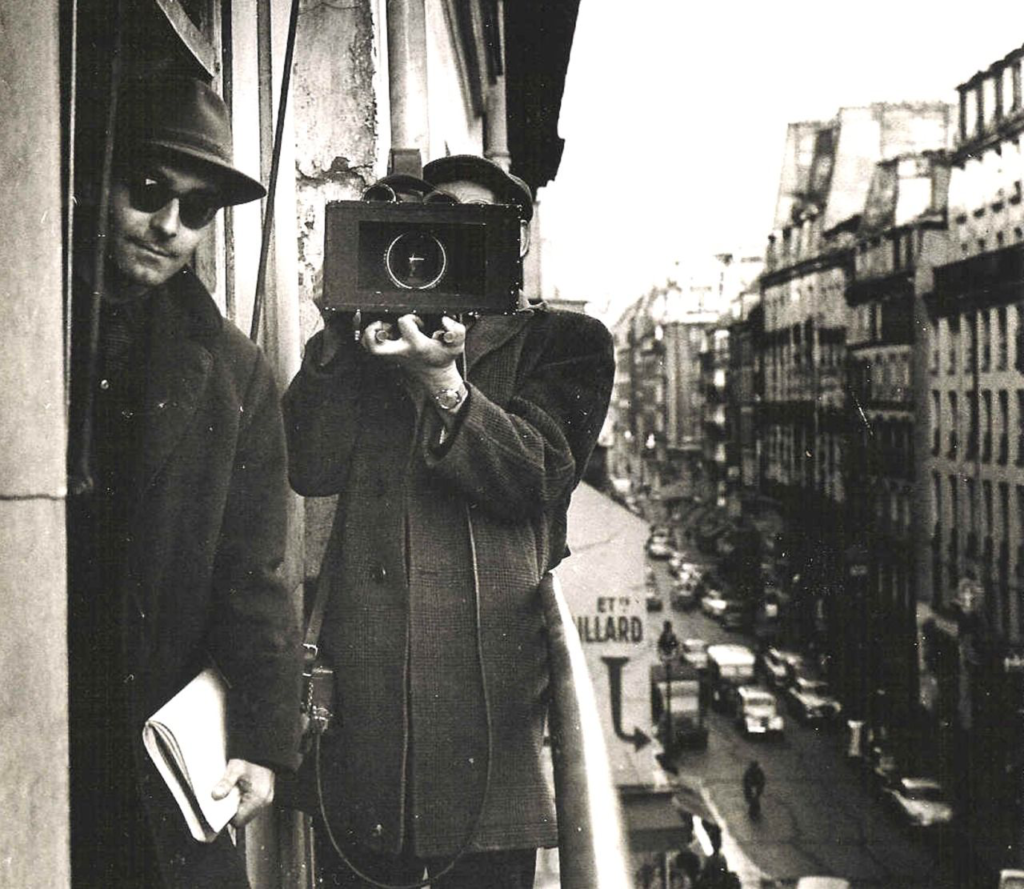

The French new wave movement is characterised by a number of narrative conventions including; non-linear storytelling, jump cuts, and improvisation. Directors often used handheld cameras to create a sense of spontaneity and realism, with many films being shot on location rather than in a studio for authenticity. The French new wave movement also emphasised personal expression and experimentation and many directors broke away from traditional narrative structures to explore new forms of storytelling.

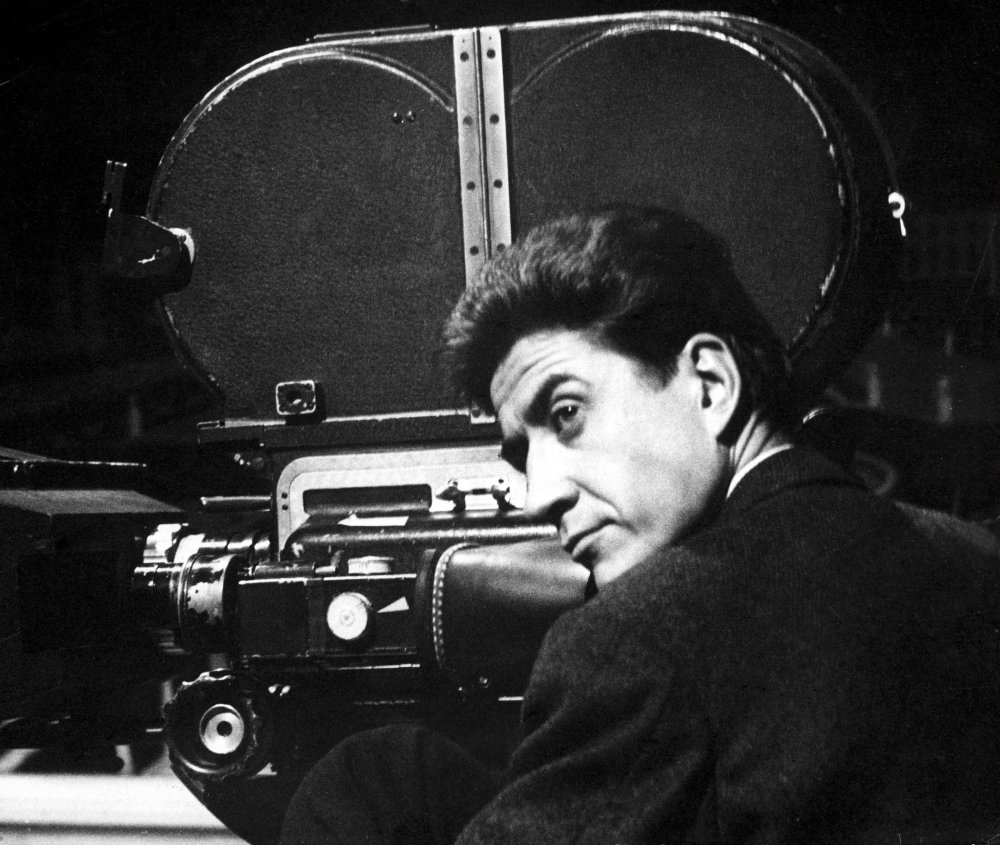

There were two different approaches to film making in the French New Wave movement, the two groups were the “Left Bank” and the “Right Bank”. The Left Bank group included directors such as Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, who tended to focus on more experimental, avant-garde filmmaking. The Right Bank group, which included directors such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, tended to be more focused on traditional narrative storytelling. While these two groups had different approaches to filmmaking, they both played a significant role in shaping the French New Wave movement.

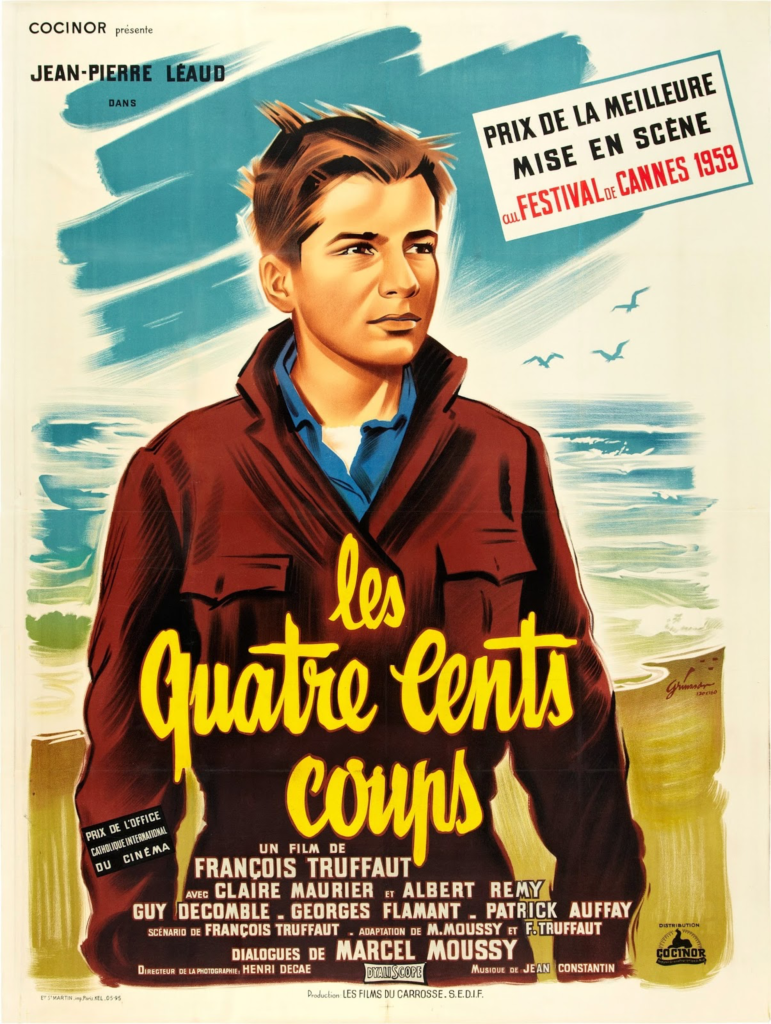

The 400 Blows remains a prime example of the stylistic innovations of the French New Wave. It is largely autobiographical, and recounts the story of an adolescent boy “raising hell” (which explains the idiomatic French title “Les Quatre Cents Coups”).

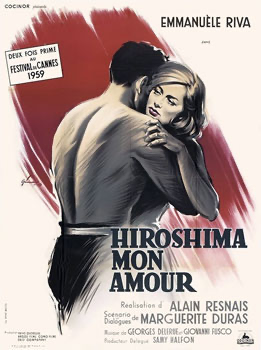

2. Hiroshima, mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959) – The deep conversation between a Japanese architect (Eiji Okada) and a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) forms the basis of this celebrated French film.

Considered one of the vanguard productions of the French New Wave. Set in Hiroshima after the end of World War II, the couple — lovers turned friends — recount, over many hours, previous romances and life experiences. The two intertwine their stories about the past with pondering the devastation wrought by the atomic bomb dropped on the city.

Alexandre Astruc constructed the auteur theory around the concept of caméra-stylo (“camera-pen”) with the idea that the director of a film (overseeing all elements of the film making process) should be more considered as the “author” of the film compared to the screenplay writer, for example. It was then developed that cinematically successful films contains an “auteurs” clear stamp, or signature, either audibly or visually in the film that makes it unique and unmistakably their own, and the audience are able to identify it as such.

Directors such as Wes Anderson and his use of very recognisable visual styles, cinematographic choices and repeated use of certain themes, deems him as an auteur.

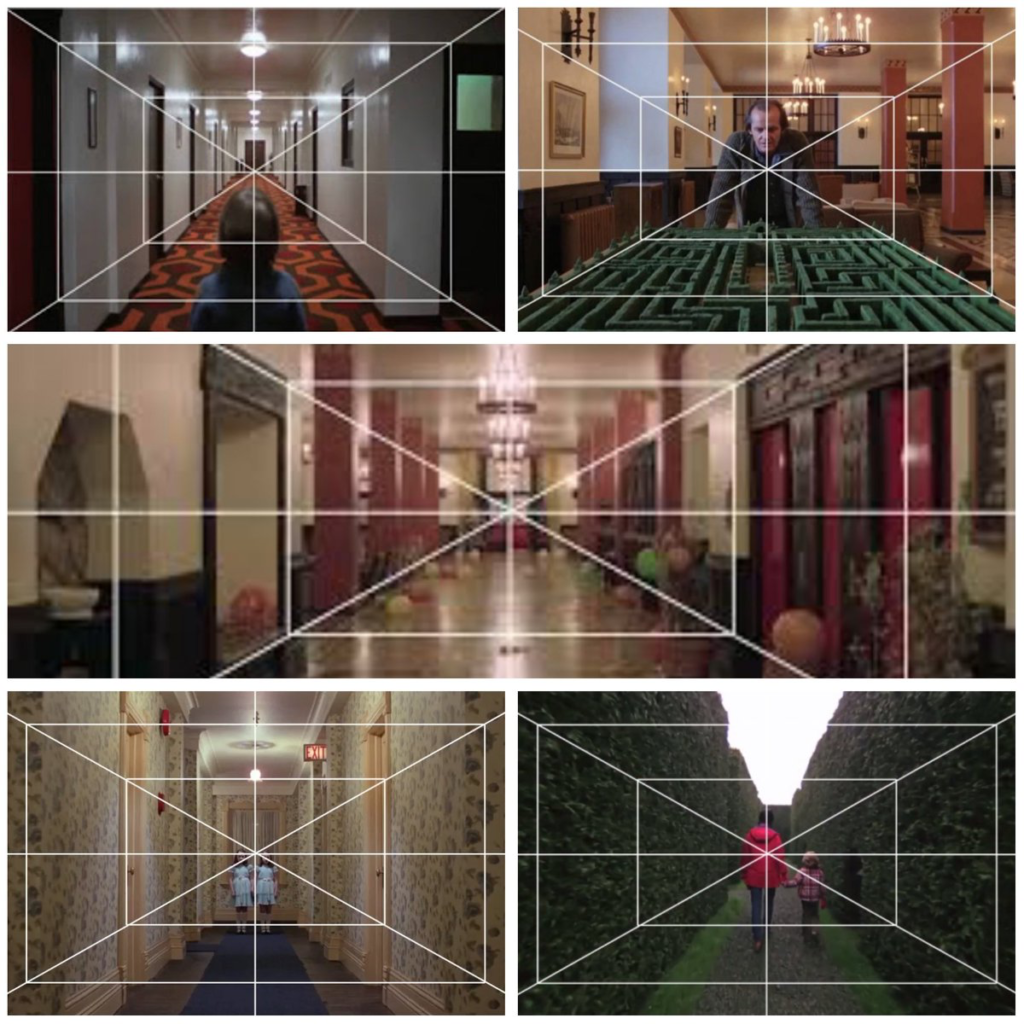

Stanley Kubrick and his consistent use of the one-point perspective shot, in which a scenes leads a viewer’s focus to a very specific point, a stylistic choice he is very well known for. Plus his use of the intense “Kubrick stare” that he repeats throughout his films, also determining him as an auteur.

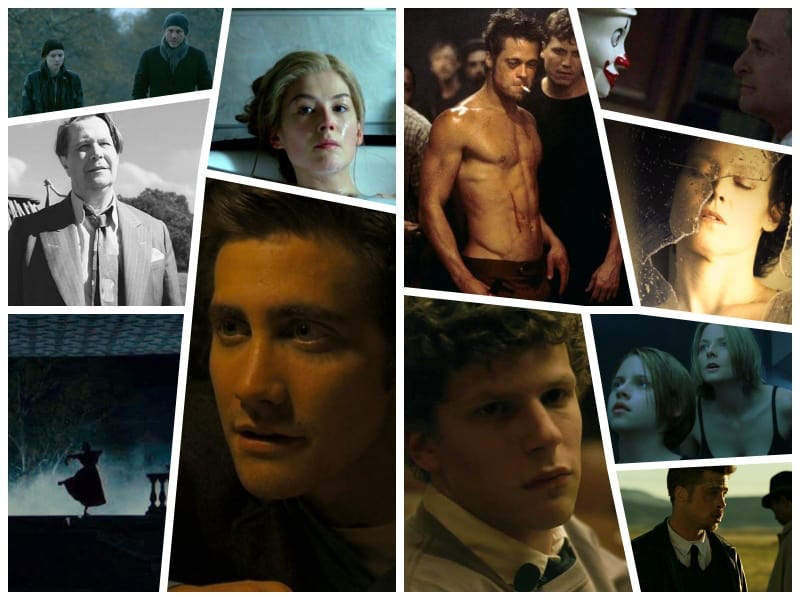

Finally, David Fincher and his repeated themes of masculinity, stylistic tones and colour palette and unique camera movements also give his films a signature look that can be easily associated to him as the auteur.

The British New Wave was a movement among young British filmmakers of the late 1950s and early 1960s who had grown up watching American and European art films and were inspired to make more of their own. The movement had an emphasis on social realism and naturalism, as well as a tendency to focus on working class characters and settings.

British New Wave films were made outside of studio control, studios rarely wanted to distribute them and so because of this, they were often shown in small specialty theatres or at film festivals.

The British New Wave was characterised by many of the same stylistic and thematic conventions as the French New Wave. Usually in black and white, these films had a spontaneous quality, often shot in a pseudo-documentary / fake documentary, style on real locations and with real people rather than extras, apparently capturing life as it happens.

The key characteristics of British New Wave Cinema include:

A few films and directors that came from British New Wave Cinema Era:

The Breakfast Club was influenced by Soviet film, specifically the use of montage. The film uses montage to demonstrate the passing of time while the students are in detention.

The Breakfast Club uses rhythmic montage in its famous dance sequence, it is an example of a montage that conveys a sense of togetherness.

Edgar Wright is one of the top directors in using rhythmic montage editing techniques. He frequently edits to the beat of the music and uses songs to help develop tension and even comedy from those moments. This is used specifically in Baby Driver in the opening of the film.

2. Over-tonal Montage: The Godfather Francis Ford Coppola (1972)

This montage links religion and murder – aspects of the mafia that are explored throughout The Godfather series. Whilst Michael renounces sin, others carry out his sinful work, this creates the juxtaposition while condensing and combining a number of dramatic moments to create one climax.

3. Tonal Montage: The Revenant Alejandro González Iñárritu (2015)

Shots with a similar theme or emotional tone edited together, such as the character’s steamy breath cuts to a foggy sky and then to smoke from a pipe.