Task 1: The context of Post-WW1 Russia.

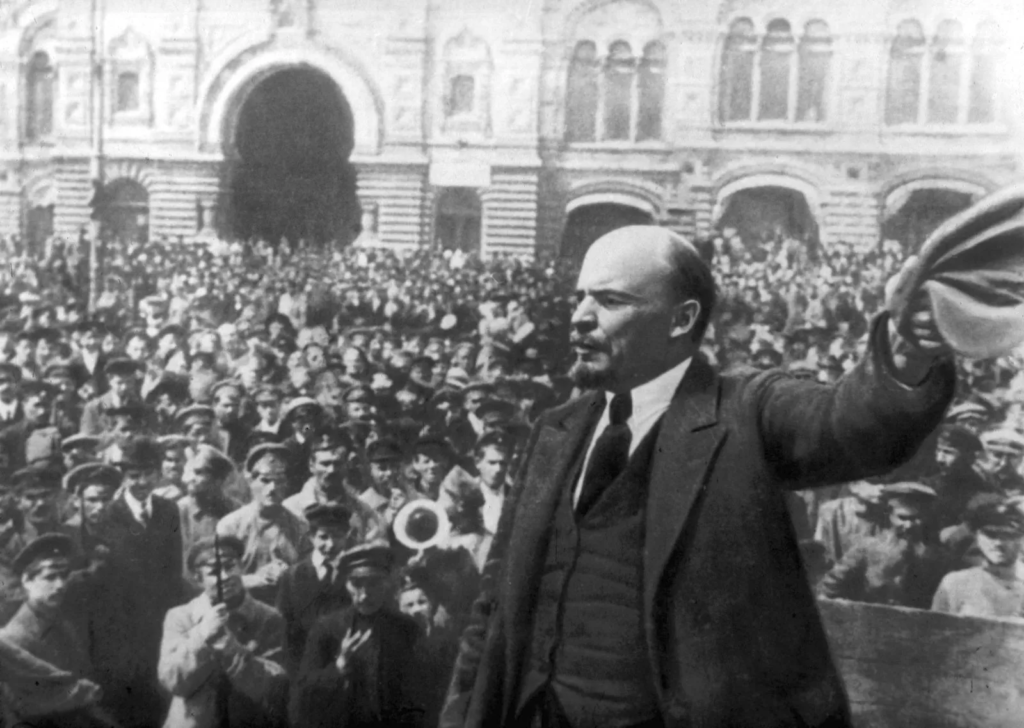

The October Revolution of 1917 was the beginning of the USSR under Communism. Lenin encouraged propaganda through film, and this led to many works that involved anti-tsarist propaganda and empowerment of workers. As well, filmmakers had to think very carefully about the films they made due to the lack of film stock early on, which encouraged the Gerasimov Institute to reuse & cut together pre-shot film to create new films entirely.

Task 2: Stylistic Conventions of Soviet Constructivism art movement.

As evident from the two artworks above, the Soviet Fine art movement consisted of two major themes: Order & simplicity, as well as exaggerated iconography.

The Communist Government of the USSR sought to control the thoughts of their subjects through propaganda in the arts, a Russian flag-carrying soviet giant storming across the streets of St Petersburg, sent a message about victory to Russian subjects.

Task 3: The Gerasimov Institute’s present operations.

The Gerasimov Institute, or VGK, is the oldest Film school in the world. Its present operations today consist of being an influential film school in Russia.

Task 4: Examples of Soviet Constructivist Films.

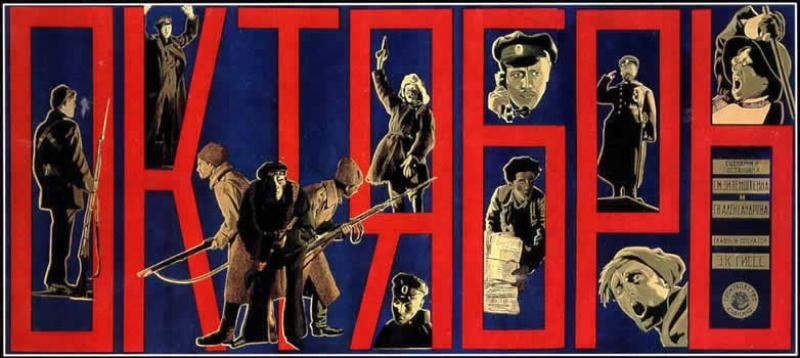

S. Esienstein, ‘October: Ten days that shook the world’, (1928).

Eisenstein’s ‘October: Ten days that shook the world’ is an example of the movement’s propaganda, in its victorious portrayal of Lenin and the Communist Revolution in Russia in 1917.

D. Vertov, ‘Kino Eye’, (1924).

Once more, the propaganda of the Soviet State can be observed in Vertov’s ‘Kino Eye’. It represents the surveillance of the state, and instils this idea into viewers.

Task 5: Films that are influenced by visual style of Soviet Constructivism.

W. Anderson, ‘Isle of Dogs’, (2018).

Wes Anderson’s use of symmetry and bold but simplistic iconography reminds me of Soviet Constructivism- in ‘Isle of Dogs’ the techniques of symmetry and symbolism, as well as deep red and grey use of colours is very similar to the soviet fine art theme.

A. Hitchcock, ‘Psycho’, (1960).

The use of montage in Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’ reminds me of Soviet Constructivism, as the pace of scenes and the viewer’s interpretation of the plot is influenced heavily by the montage technique Hitchcock uses, depending on the scene.

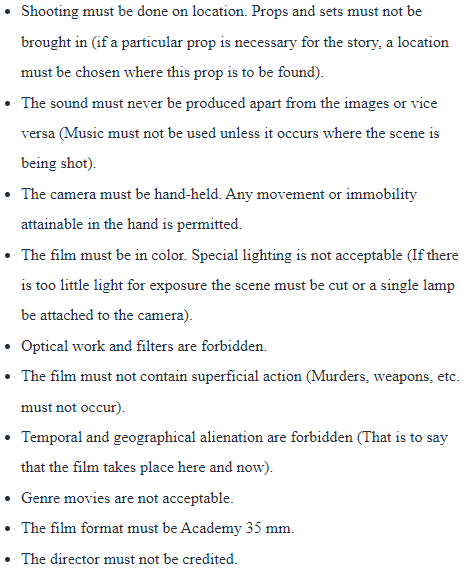

Task 6: 3 methods of montage in Film.

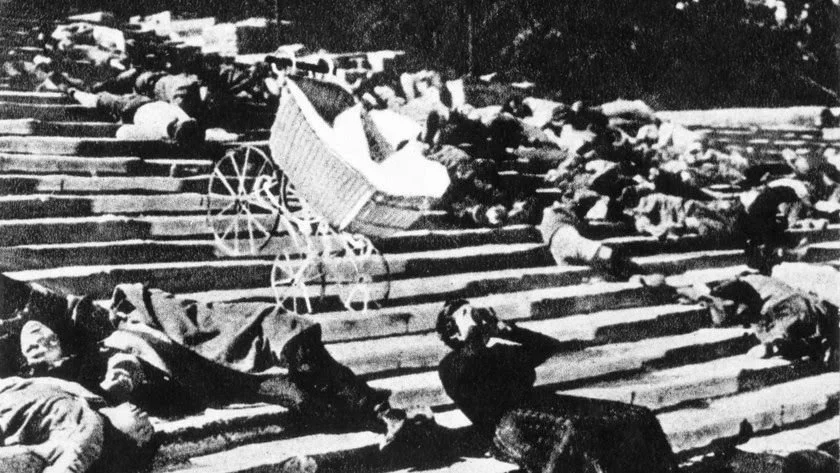

Metric Montage:

Metric Montage involves creates visual spacing within a scene by cutting to the next shot immediately after a sequence of frames, no matter the context.

An example can be found in ‘Battleship Potemkin’ by Sergei Eisenstein, (1925), where repeating patterns of chaos and people weeping cut back to the baby in the stroller rolling down the Odessa Steps.

Rhythmic Montage:

Rhythmic montage is the cutting of clips based on the action of image of a shot, with consideration of musical pacing.

An example can be found in ‘The Untouchables’ by Brian De Palma, (1987), where the ‘Odessa Steps’ scene is recreated inter-textually as shots line up with music.

Tonal Montage:

Tonal Montage is the practice of editing together two shots with a similar tone, but often different context.

An example of this can be found in ‘Whiplash’ by Damien Chazelle, (2015), where Andrew’s persistence and gradual downfall is implied through his vigorous drumming, obsession with music and physical illness: all portrayed through tonal montage, where shots cut between bloodied drumsticks, drumming and metronomes.