Editing is a key factor within film when it comes to maintaining the flow and rhythm of a narrative or scene. Within Damien Chazelle’s 2014 film Whiplash, particularly in the final scene of the picture, he uses fast-paced, harsh editing techniques to constantly build tension – keeping audiences on the edge of their seats for the entirety of the scene’s duration.

The final scene begins with a heavy sense of defeat; with longer takes for each shot, contrasting the more rapid movements between scenes when Miles Teller’s character, Andrew, is focused and playing the drums, of which those match on action shots seem to create a feeling of triumph as Andrew is more ‘in his element’. However, within this section, Andrew’s father, played by Paul Reiser, is rushing to comfort him, in a combination of various short-take shots that Chazelle used to display the unconditional support Andrew’s father has for him, despite not understanding Andrew’s passion himself.

Each take begins to decrease in length gradually as Andrew walks back onto the stage, unwilling to give up after J.K. Simmons’ character, Fletcher, set him up to fail. The use of this technique quickly turns the feeling of hopelessness into a tense, exciting atmosphere that builds the foundation for the conclusion of the film. Chazelle’s intent here is clearly to keep the audience interested right up until the last second of the film’s runtime, much like how he did with the rest of the film, constantly asking the question of how far Andrew will go to achieve his goal.

Andrew’s final performance begins abruptly, with an unexpected shot change that careers the tone of the scene back into a high-speed rhythmic montage that the audience is used to. The next few shots grow closer toward Andrew’s face with each cut, presenting Andrew’s seething hatred and desire to prove Fletcher wrong – creating what could be considered a non-physical fight scene as Andrew plays. Chazelle then implements various takes of the cello player, brass players and Fletcher as a sort of tonal montage to enhance volume of each instrument the characters play, their faces showing a mix of confusion whilst still trying to keep up the façade of professionalism in front of their audience. Each shot begins to change angles suddenly, matching the violent drumming of Andrew and the conflict between him and Fletcher, the pace of every change matching the tempo of the music, which aids in developing the rhythmic montage here.

Further on in the scene, Chazelle uses several instances of shot-reverse-shots – that also function as eyeline matches – using whip-pan effects during transitions between each shot to present the non-verbal communication between the two as Fletcher attempts to end the performance – Andrew persevering and continuing to play.

This section of the scene is where Chazelle truly shows Andrew’s focus and dedication to his craft – the audio has been edited to become asynchronous – conveying his exhaustion and creating a moment of reflection for the audience toward all he has sacrificed to get this far, before breaking the tension in the finale, finishing his performance and ending the sequence.

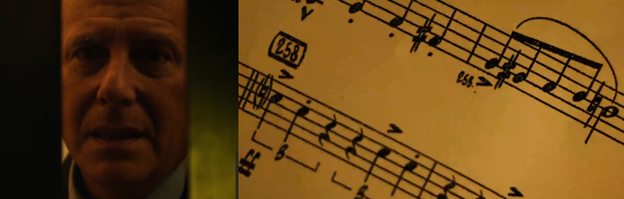

Chazelle also makes use of the Kuleshov Effect several times throughout this scene; the two most obvious examples being the shot of Andrew’s father through the gap in the door, and the music sheets. It helps to form stronger links and associations between each shot that the audiences have gradually familiarized themselves with throughout the duration of the film.

In conclusion, without Chazelle’s use of editing techniques in Whiplash, the drama and tension in the film would be nowhere near as high-stakes as it feels watching the plot of the narrative unfold. The editing constantly aids the progression of the film, and feels like a song in itself, with the fast cuts acting as a tempo.